Allen test

The Allen test is a simple, non-invasive bedside manoeuvre developed to assess the patency of the radial and ulnar arteries and evaluate the adequacy of collateral circulation to the hand via the palmar arches.

Originally devised in 1929 by Edgar Van Nuys Allen (1900-1961) to detect arterial occlusion in the context of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). The test has since been widely adopted in contexts including pre-procedural screening for radial artery cannulation, arterial blood gas sampling, and radial artery harvest for coronary bypass surgery or forearm flap procedures.

The more commonly used Modified Allen Test (MAT) was proposed by Irving Sherwood Wright (1901-1997) in 1952, shifting the manoeuvre from a bilateral hand comparison to a unilateral hand assessment, which better isolates vascular integrity per limb and improves usability in clinical scenarios.

Clinical Use and Interpretation

The Allen test remains a common screening tool for assessing the adequacy of collateral perfusion from the ulnar artery before procedures that may compromise radial artery flow.

- A normal (positive) result is indicated by prompt return of hand colour (typically within 5 to 10 seconds) following release of one artery.

- A delayed or absent colour return is considered abnormal (negative), suggesting poor collateral supply and increased risk of ischaemia should the tested artery be compromised.

However, the diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility of the Allen test have been the subject of ongoing debate. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses report a sensitivity ranging from 66–78% and specificity from 81–97%, depending on the technique and timing criteria used. Studies have shown that even with a “normal” test, radial artery occlusion or ischaemic complications can still occur. Furthermore, some ischaemic complications have been documented despite an adequate test result, and conversely, many patients with “abnormal” results undergo procedures without adverse effects.

Variations and Evolving Standards

Several modifications and adjunctive techniques have been proposed to improve the objectivity and reproducibility of the test. These include:

- Three-digit compression techniques for better arterial occlusion control

- Pulse oximetry and plethysmography to reduce reliance on visual pallor assessment

- Doppler ultrasonography as the current gold standard for evaluating hand arterial flow and palmar arch completeness

Despite its limitations, the test persists in clinical routines largely due to its simplicity and zero cost. Yet, modern guidelines increasingly recommend Doppler-based assessment, particularly when planning radial artery harvesting for CABG, where objective evidence of complete arch circulation is preferred.

Typical Use Today

- Routinely used before radial artery cannulation or harvest

- Supplemented or replaced by Doppler ultrasound in high-stakes procedures

- Not universally predictive of ischaemic risk but still used as a screening threshold

History of the Allen test

Classic Allen Test

1929 – Edgar Van Nuys Allen introduced his test while at the Mayo Clinic, as part of a broader strategy to diagnose thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) in patients with suspected chronic occlusive arterial lesions distal to the wrist. Dissatisfied with reliance on pulsations alone, Allen devised a simple bedside method to evaluate patency of the ulnar and radial arteries by observing the return of colour to the hand following deliberate occlusion and reperfusion.

His original description emphasised bilateral hand examination, occlusion of one artery at a time following fist clenching, and assessment of reactive hyperaemia i.e., the return of rubor, as a surrogate for adequate collateral flow. The classic bilateral Allen test is performed as follows:

- The patient elevates both arms and clenches their fists tightly for approximately one minute to exsanguinate the hands.

- The examiner locates both radial arteries by palpation and applies digital pressure to occlude both simultaneously at the wrist.

- The patient then opens both hands without hyperextension, and the examiner releases pressure from one artery at a time, observing for return of coluor to the hand and fingers.

- A rapid return of colour (usually within 5–10 seconds) indicates an intact and functional artery and palmar arch. Delayed or absent return suggests occlusion or inadequate collateral flow.

Allen emphasized that the test helps differentiate occlusion in the ulnar vs radial artery depending on which vessel is released.

Modified Allen Test

1952 – Irving Sherwood Wright (1901-1997) proposed an initial refinement in clinical lectures as the Modified Allen Test (MAT) as a unilateral variant more practical in modern clinical settings. This technique avoids the need for bilateral comparison and allows for more controlled assessment of individual limb perfusion.

- The patient elevates one hand above the heart and clenches their fist tightly for about 10 seconds.

- The examiner applies pressure to both the radial and ulnar arteries at the wrist to occlude blood flow.

- The patient opens the hand in a relaxed and neutral position.

- The examiner releases pressure on the ulnar artery only, observing the palm for capillary refill and return of normal colour.

- Time to full perfusion is recorded; <6 seconds is generally considered normal. The process is then repeated for the radial artery, and again on the contralateral hand.

1966 – Borje Ejrup, Boguslav Fischer and Irving S. Wright publish Clinical evaluation of blood flow to the hand: The false-positive Allen test and challenge the reliability of the Allen Test. The paper systematically critiques the accuracy of the Allen test by comparing clinical findings with direct intra-arterial pressure measurements and operative findings in 57 patients. They demonstrate that a “positive” Allen test (suggesting adequate collateral flow) may still occur in patients with inadequate or absent ulnar arterial flow, especially in the setting of radial artery ligation or harvest planning.

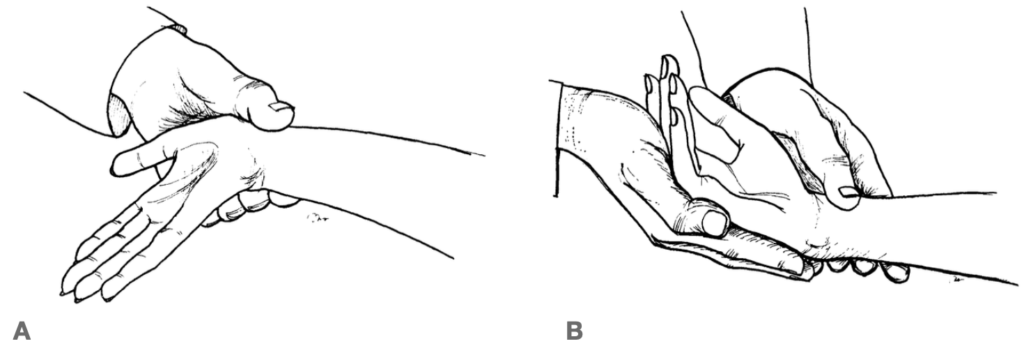

B: Suggested modification: Patient is forced by the examiner’s hand not to hyperextend; told to open the hand rapidly but only partially, and to relax their fingers in the examiner’s hand. The patient’s wrist should relax in a slightly flexed position. Erjup et al 1966

Three-Digit Allen’s Test

2007 – Mohammed Asif and Pradip K. Sarkar publish a modified Allen test technique designed to reduce false negatives, particularly before radial artery harvest. The modification is based on anatomical insight that proximal branches of the radial artery (not compressed in standard thumb, or two-finger technique) may falsely perfuse the hand via the palmar carpal arch thus creating a misleading “normal” result.

The method involves compressing both the radial and ulnar arteries using three fingers each, ensuring full occlusion across the artery’s breadth, especially proximally near the wrist crease.

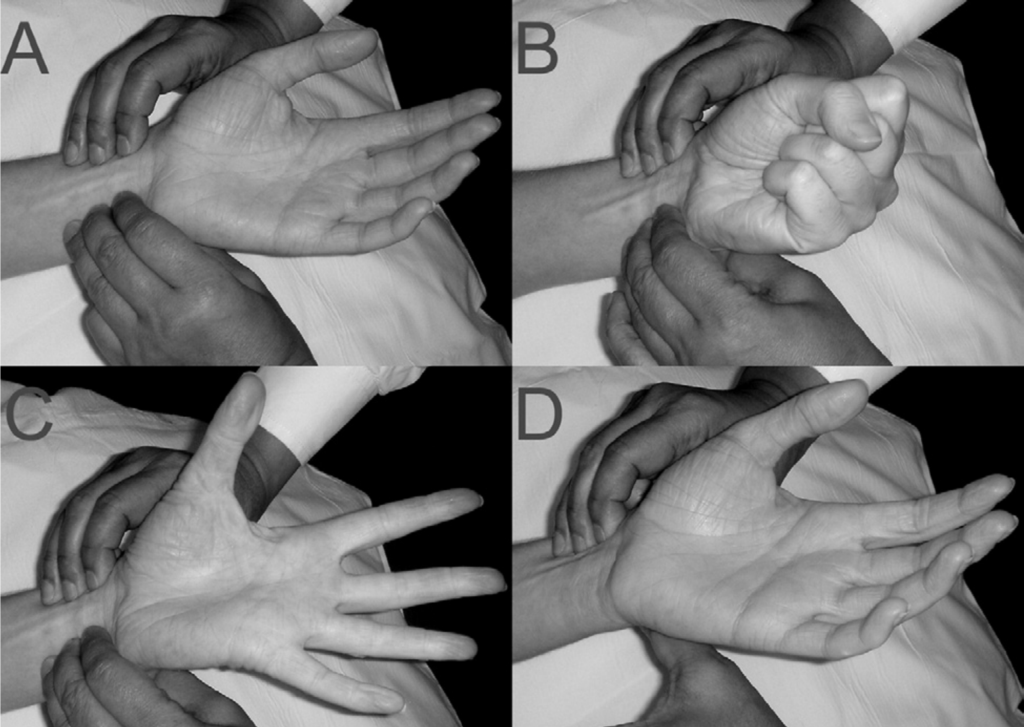

- Compress both arteries with three fingers each at the wrist.

- Have the patient clench and unclench their fist 10 times.

- With both arteries still compressed, the hand is held relaxed and partially open (not hyperextended).

- Release the ulnar artery and observe for capillary refill particularly the thumb and thenar eminence.

- Refill time >6 seconds is considered a positive test, indicating inadequate collateral flow.

The authors report using the technique in over 600 cases with no post-op vascular insufficiency following radial artery harvest, supporting its real-world efficacy.

B: With both arteries compressed the subject is asked to clench and unclench the hand 10 times. The hand is then held open, ensuring that the wrist and fingers are not hyperextended and splayed out.

C: The palm is observed to be blanched.

D: The ulnar artery is released and the time taken for the palm and especially the thumb and thenar eminence to become flush is noted. The modified three-digit Allen’s test. Asif 2007.

Diagnostic Accuracy and Performance: Allen Test and Modified Allen Test

As objective technologies like Doppler ultrasonography, plethysmography, and pulse oximetry emerged in the late 20th century, the Allen test underwent increasing scrutiny. A series of studies from 1985 onwards investigated its sensitivity, specificity, and clinical predictive value, often using imaging or intra-arterial pressures as reference standards.

1985 – Wilkins published the first major comparison of Allen test with Doppler ultrasonography. They found significant inter-observer variability and false negatives and raised concern about the lack of standardised timing or objective endpoint.

2000 – Jarvis compared Modified Allen Test (MAT) to Doppler in 61 patients. They reported a sensitivity of 54.5% and specificity of 91.7%. The best performance when reflow occurred within 6 seconds. They concluded that MAT is not sufficiently sensitive to rule out arterial insufficiency on its own.

2001 – Ruengsakulrach published two anatomical and clinical studies published in Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery investigating variation in palmar arch anatomy and its implications for radial artery harvest. They found that even with a “normal” Modified Allen Test, angiographic and cadaveric studies revealed incomplete superficial palmar arches in a significant minority of patients. The studies reinforced that MAT could fail to detect critical anatomical variants, and advocated routine use of Doppler or intra-arterial imaging to confirm collateral adequacy before surgery.

Barbeau Test: Pulse Oximetry and Plethysmography

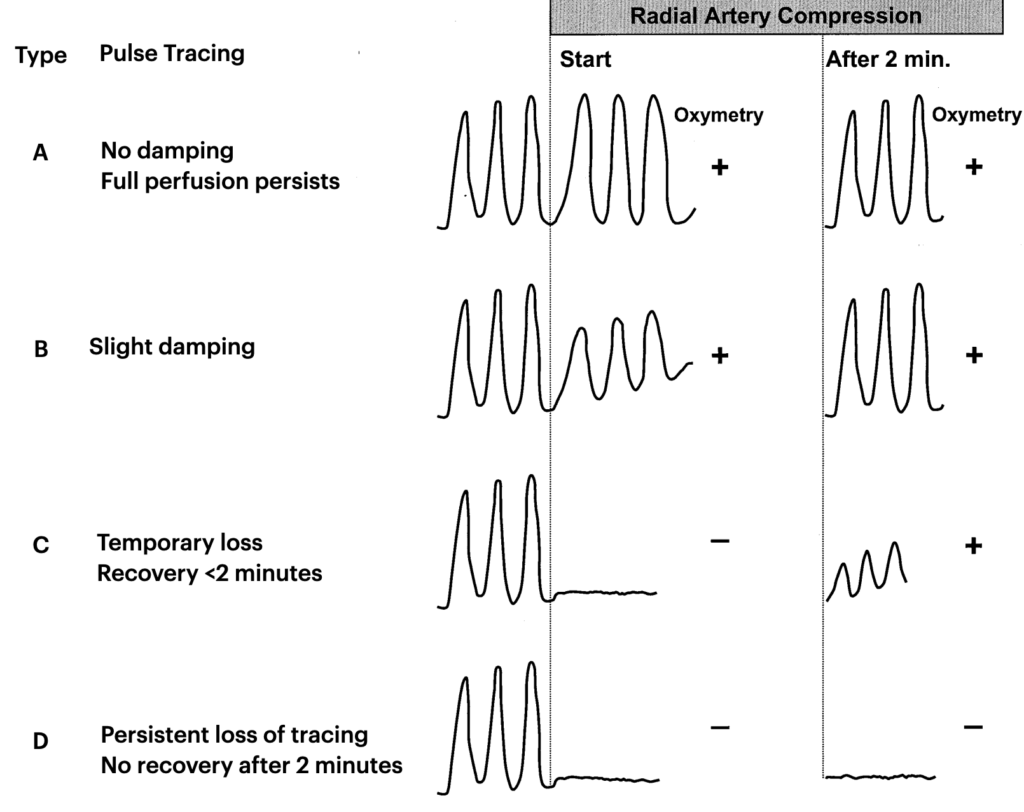

2004 – Gérald R. Barbeau published a study comparing the Modified Allen Test (MAT) with a dual assessment using pulse oximetry and plethysmography (PL/OX) in 1,010 patients undergoing evaluation for transradial cardiac catheterisation.

They proposed an objective four-tier classification system based on the degree of pulse tracing loss during radial artery compression:

Only 1.5% of patients were excluded based on PL/OX types (vs 6.3% by MAT), making the method significantly more sensitive and inclusive.

This technique gained widespread interest in interventional cardiology and critical care, particularly as it allowed automated signal detection, reduced subjectivity, and provided real-time waveform documentation.

AHA Guidelines: MAT and Barbeau not required

2018 – The American Heart Association (AHA) shifted the clinical emphasis entirely. Their scientific statement on transradial access (TRA) for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) stated:

Routine performance of the Allen or Barbeau test is not required prior to TRA. The incidence of hand ischemia is very low… and other factors such as bleeding risk, operator experience, and catheter-to-artery ratio are more predictive of outcomes.

This position cemented a modern clinical consensus: adequate collateral flow is desirable, but neither MAT nor Barbeau testing is independently predictive of ischaemic complications. Instead, TRA is considered safe as default, with perfusion monitoring and prompt recognition of complications taking precedence.

Key Interpretation Points

- High specificity: A truly abnormal test often correlates with inadequate flow.

- Low to moderate sensitivity: A “normal” test does not reliably exclude ischaemic risk.

- False positives may occur due to wrist extension or inadequate compression; wrist flexion and complete hand relaxation are recommended to improve accuracy.

- Diagnostic value depends heavily on standardisation of technique, timing, and patient anatomy.

- Three-digit compression of both arteries provides more reliable occlusion.

- Adjuncts such as pulse oximetry, plethysmography, or Doppler ultrasonography enhances objectivity and reduces user bias.

Associated Persons

- Edgar Van Nuys Allen (1900-1961)

- Irving Sherwood Wright (1901-1997)

Alternative names

- Allen’s test

- Modified Allen Test

References

Historical references

- Allen EV. Thromboangiitis obliterans: methods of diagnosis of chronic occlusive arterial lesions distal to the wrist with illustrative cases. Am J Med Sci 1929;178(2): 237-244

- Wright IS. The Allen Test. In: Vascular diseases in clinical practice (2e) 1952: 38-39

- Ejrup B, Fischer B, Wright IS. Clinical evaluation of blood flow to the hand. The false-positive Allen test. Circulation. 1966 May;33(5):778-80.

Eponymous term review

- Baumann DP. The specificity of the Allen test in obliterative vascular disease. Angiology. 1954 Feb;5(1):36-8

- Wilkins RG. Radial artery cannulation and ischaemic damage: a review. Anaesthesia. 1985 Sep;40(9):896-9.

- Cable DG, Mullany CJ, Schaff HV. The Allen test. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999 Mar;67(3):876-7.

- Jarvis MA, Jarvis CL, Jones PR, Spyt TJ. Reliability of Allen’s test in selection of patients for radial artery harvest. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000 Oct;70(4):1362-5.

- Ruengsakulrach P, Brooks M, Hare DL, Gordon I, Buxton BF. Preoperative assessment of hand circulation by means of Doppler ultrasonography and the modified Allen test. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001 Mar;121(3):526-31.

- Ruengsakulrach P, Buxton BF, Eizenberg N, Fahrer M. Anatomic assessment of hand circulation in harvesting the radial artery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001 Jul;122(1):178-80.

- Barbeau GR, Arsenault F, Dugas L, Simard S, Larivière MM. Evaluation of the ulnopalmar arterial arches with pulse oximetry and plethysmography: comparison with the Allen’s test in 1010 patients. Am Heart J. 2004 Mar;147(3):489-93.

- Kohonen M, Teerenhovi O, Terho T, Laurikka J, Tarkka M. Is the Allen test reliable enough? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007 Dec;32(6):902-5.

- Asif M, Sarkar PK. Three-digit Allen’s test. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007 Aug;84(2):686-7.

- Appio MR, Swan KG. Edgar Van Nuys Allen: the test was only the beginning. Ann Vasc Surg. 2011 Feb;25(2):294-8

- Habib J, Baetz L, Satiani B. Assessment of collateral circulation to the hand prior to radial artery harvest. Vasc Med. 2012 Oct;17(5):352-61.

- Bertrand OF, Carey PC, Gilchrist IC. Allen or no Allen: that is the question! J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 May 13;63(18):1842-4.

- Romeu-Bordas Ó, Ballesteros-Peña S. Validez y fiabilidad del test modificado de Allen: una revisión sistemática y metanálisis [Reliability and validity of the modified Allen test: a systematic review and metanalysis]. Emergencias. 2017 Abr;29(2):126-135.

- Mason PJ et al. An Update on Radial Artery Access and Best Practices for Transradial Coronary Angiography and Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Sep;11(9):e000035.

- Elwali A, Moussavi Z. The modified Allen test and a novel objective screening algorithm for hand collateral circulation using differential photoplethysmography for preoperative assessment: a pilot study. J Med Eng Technol. 2020 Feb;44(2):82-93.

- Golamari R, Gilchrist IC. Collateral Circulation Testing of the Hand- Is it Relevant Now? A Narrative Review. Am J Med Sci. 2021 Jun;361(6):702-710.

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

BSc MD University of Western Australia. Interested in all things critical care and completing side quests along the way

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |