Kernohan-Woltman Notch Phenomenon

Kernohan-Woltman Notch Phenomenon (KWNP) is a false localising sign that occurs in the context of transtentorial (uncal) herniation. The phenomenon results from compression of the contralateral cerebral peduncle (crus cerebri) against the tentorial edge, leading to motor weakness on the same side as the original lesion. This paradoxical presentation is contrary to typical neuroanatomical expectations.

What is a “false localising sign”?

A false localising sign refers to a clinical feature that suggests damage to a region not actually involved in the primary pathology. In KWNP, the motor deficit appears ipsilateral to the supratentorial lesion, not because of cortical injury or lateralisation error, but due to remote compression of the corticospinal tract in the opposite midbrain.

Clinical Presentation

Ipsilateral hemiparesis to the expanding lesion (e.g. right subdural haematoma ➜ right-sided weakness). Often accompanied by signs of brainstem compression, such as:

- Altered consciousness

- Third nerve palsy

- Posturing or decerebrate rigidity

This paradoxical hemiparesis may lead to diagnostic confusion and has historically resulted in incorrect surgical lateralisation and operating on the side of weakness rather than the lesion.

Pathophysiology

KWNP is a complication of uncal herniation, a subtype of transtentorial herniation where the medial temporal lobe (uncus) is displaced downward through the tentorial notch. As intracranial pressure builds, this displacement forces the contralateral cerebral peduncle against the tentorial edge, compressing descending corticospinal fibres before decussation in the medulla.

This results in disruption of motor pathways on the side opposite the compressed peduncle, but same side as the lesion, hence the clinical paradox.

Imaging Features

Typical radiological finding:

An indentation of the contralateral cerebral crus (the Kernohan notch) adjacent to the tentorial edge, correlating with ipsilateral clinical motor signs

CT Brain

May show mass effect and midline shift, though direct identification of peduncular notching is difficult. Useful for identifying the primary lesion (e.g. hematoma, tumour, edema) and assessing signs of herniation.

MRI Brain

Superior for identifying the notch deformity of the contralateral cerebral peduncle. T2-weighted imaging may demonstrate leukomalacia or signal change in the compressed crus cerebri.

Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI) may reveal:

- Reduced fractional anisotropy

- Disrupted fibre tractography in the affected corticospinal tract

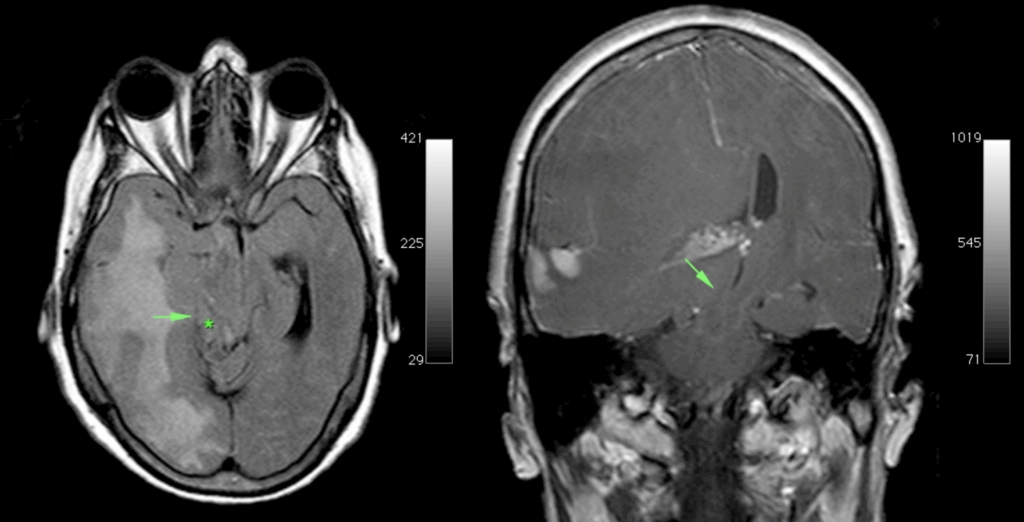

Mass effect of the tumour, with medial part (uncus) of the right temporal lobe (arrow) is herniating over the edge of the tentorium (*) compressing the mesencephalon against the free edge of the contralateral tentorium and causing a notch on the left side. Case courtesy of Erik Ranschaert, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 10967

Prognosis and Recovery

Outcomes are variable. Partial to full recovery of motor function is possible, especially with timely decompression and supportive care.

A 2016 systematic review found that ~67% of KWNP cases had measurable motor recovery, though some patients are left with persistent weakness or spasticity.

History of the Kernohan-Woltman Notch Phenomenon

1927 – Groeneveld and Schaltenbrand publish “Ein Fall von Duraendotheliom über der Großhirnhemisphäre mit einer bemerkenswerten Komplikation: Läsion des gekreuzten Pes pedunculi durch Druck auf den Rand des Tentoriums”. They describe a 43‑year‑old man with a left sylvian–fissure tumour, right‑sided shift, and left‑hemiparesis, at necropsy revealing a “notch” in the contralateral pes pedunculi produced by the tentorial edge.

1928 – James Watson Kernohan (1896–1981) and Henry William Woltman (1889-1964) report a single case of ipsilateral hemiparesis with a supratentorial lesion and, at autopsy, an indentation (“incisura”) of the crus cerebri contralateral to the tumour.

1929 – Kernohan and Woltman published “Incisura of the crus due to contralateral brain tumour” in the Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. This comprehensive article went well beyond their initial single-case report, presenting a series of cases in which ipsilateral hemiparesis contradicted expected localising principles.

[There is] a discrepancy between the seat of the lesion and the side of the motor defect — which demands consideration in connection with a known mechanical distortion of midbrain structures.

Notching of the crus cerebri by the free margin of the tentorium could, we believe, explain the homolateral signs of the pyramidal tract noted in most of our cases

Kernohan & Woltman, 1929

The paper analysed several autopsy-confirmed cases with supratentorial lesions, all showing a “notch” in the contralateral crus cerebri (cerebral peduncle). For the first time, the authors attempted to rationalise clinical signs with pathological findings, correlating ipsilateral hemiparesis to contralateral peduncular damage, induced by transtentorial herniation.

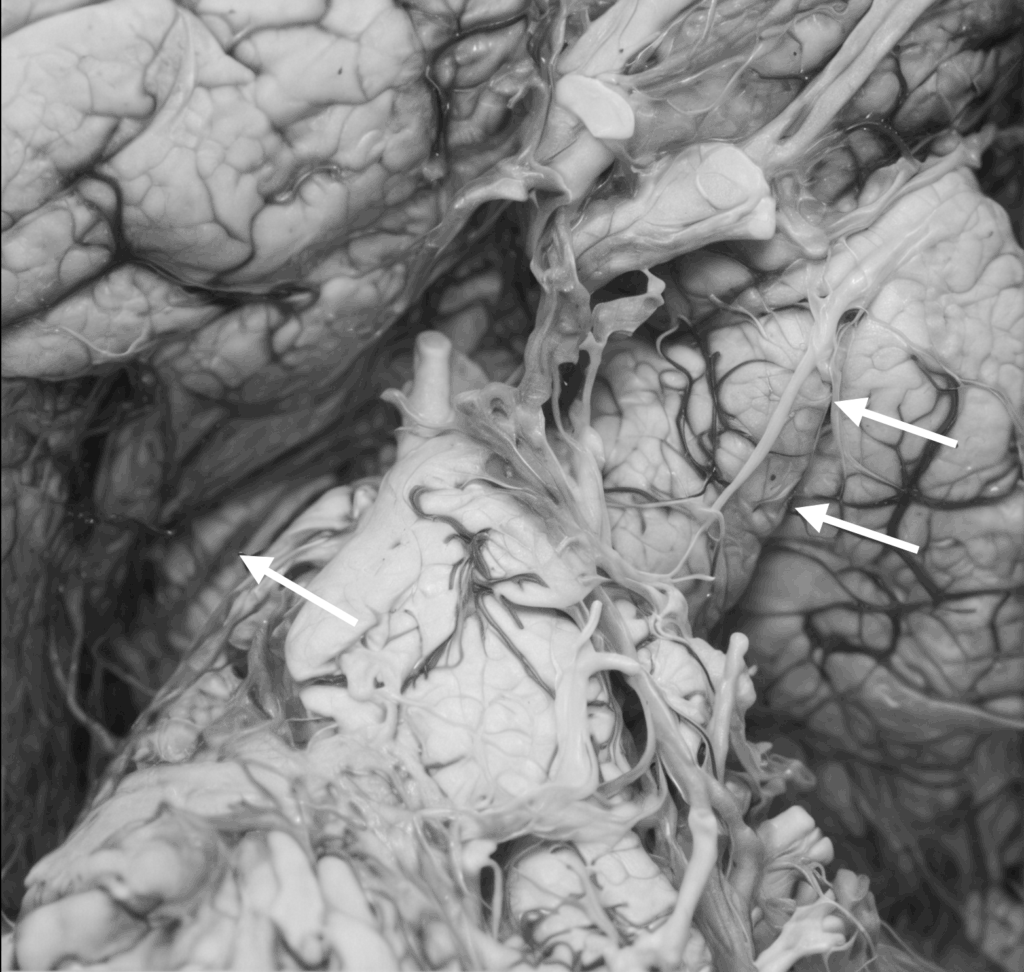

Although they didn’t coin the term “false localising sign” (which came later), the paper laid the conceptual groundwork by showing that pressure effects could mislead localisation. The paper also reproduced and expanded upon their 1928 figures, including gross anatomical images demonstrating the notch.

Notably, they acknowledged the Groeneveld & Schaltenbrand case (1927), positioning their own findings as part of an evolving understanding of brain shift effects.

The notch itself was interpreted as a result of the contralateral cerebral peduncle being compressed against the rigid tentorial edge by midline brain shift. Over time, this mechanical force led to demyelination and necrosis of descending corticospinal fibres, the structural basis of the paradoxical hemiparesis.

The phenomenon described is not merely of academic interest; it bears directly on problems of localisation, diagnosis, and surgical approach in cases of brain tumour.

Kernohan & Woltman, 1929

2004–2014 Dr. Iraj Derakhshan introduced a critical reinterpretation of KWNP, arguing that ipsilateral motor signs might not simply result from mechanical compression of the corticospinal tract. Instead, he proposed a physiological model grounded in interhemispheric diaschisis, suggesting that dominant hemisphere lesions impair motor function bilaterally, especially through disruptions in callosal excitation and control of respiration-linked consciousness.

He also contested the historical attribution of ipsilateral findings to mechanical notching alone, proposing that some of Kernohan and Woltman’s “baneful experiences” were likely due to these less appreciated interhemispheric dynamics.

2014 – Safavi-Abbasi et al defended the classic model. This group reaffirmed KWNP as a clinicopathological entity, attributing the phenomenon squarely to transtentorial herniation and direct peduncular compression. They acknowledged imaging advances but maintained that the hallmark remains a mismatch between lesion side and motor deficit, usually resolved by MRI.

2023 – Perhaps the most robust modern reappraisal came from Carrasco-Moro and colleagues, who reviewed over 100 cases of ipsilateral hemiparesis (IH) diagnosed with contemporary imaging (CT/MRI, DTI). They confirmed that:

- Most IH cases occurred acutely, often due to traumatic brain injury.

- 61 cases showed identifiable structural lesions in the contralateral cerebral peduncle (SLCP).

- These lesions, while variable, were pathologically consistent with those described by Kernohan and Woltman.

- Additional mechanisms (uncrossed CSTs, diaschisis) were proposed, but KWNP remained the most consistent pathophysiological model.

Importantly, their findings dispelled earlier notions that peduncular notching was merely an incidental artifact, reestablishing KWNP’s clinical validity through structural imaging and neurophysiological testing

2025 – Recent case literature, such as the report by Negrão et al., highlights KWNP’s relevance in real-world emergency medicine. They presented a patient with subdural haematoma and ipsilateral hemiparesis, emphasising that awareness of KWNP can shape early diagnosis and influence surgical decision-making especially in contexts like hypertensive crisis or uraemic bleeding. Their case reiterates that, although rare, KWNP remains a critical clinical consideration when standard neuroanatomical rules appear violated.

Defining False Localising Signs

KWNP stands as a paradigmatic false localising sign, where clinical symptoms suggest a lesion in a location opposite the true anatomical source. Unlike “non-localising” signs (e.g., global symptoms from raised ICP), false localising signs mislead by mimicking localised damage. KWNP underscores the limits of neuroanatomical deduction in the face of mechanical distortion and has informed broader understanding of other such signs (e.g., abducens palsy, dilated pupils in raised ICP).

Terminological Clarification

The term Kernohan’s notch can cause confusion, as it is used in two different contexts:

- Kernohan-Woltman Notch Phenomenon (KWNP) = ipsilateral hemiparesis due to contralateral midbrain crus compression. Here “Kernohan’s Notch” is a depression in the cerebral peduncle from tentorial edge pressure. This is the classic neurological phenomenon.

- Kernohan’s Notch (optic) = indentation of optic chiasm from vascular pulsations with no associated motor symptoms. In 1953, Rucker and Kernohan described notching of the optic chiasm by overlying arteries in pituitary tumors, a distinct ophthalmological concept.

Associated Persons

- James Watson Kernohan (1896-1981)

- Henry William Woltman (1889-1964)

References

Historical references

- Groeneveld A, Schaltenbrand G. Ein Fall von Duraendotheliom über der Großhirnhemisphäre mit einer bemerkenswerten Komplikation: Läsion des gekreuzten Pes pedunculi durch Druck auf den Rand des Tentoriums. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Nervenheilkunde. 1927; 97: 32-50, 1927

- Kernohan JW, Woltman HW. Incisura of the Crus Due to Contralateral Brain Tumor, Proceedings of the staff meetings of the Mayo Clinic 1928; 3(10): 69-70

- Kernohan JW, Woltman HW. Incisura of the crus due to contralateral brain tumor. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 1929; 21(2): 274–287

Eponymous term review

- Ranschaert E. Kernohan phenomenon. Radiopaedia

- Adler DE, Milhorat TH. The tentorial notch: anatomical variation, morphometric analysis, and classification in 100 human autopsy cases. J Neurosurg. 2002 Jun;96(6):1103-12.

- Derakhshan I. Kernohan notch. J Neurosurg. 2004 Apr;100(4):741-2; author reply 742.

- Zafonte RD, Lee CY. Kernohan-Woltman notch phenomenon: an unusual cause of ipsilateral motor deficit. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 May;78(5):543-5

- Moon KS, Lee JK, Joo SP, Kim TS, Jung S, Kim JH, Kim SH, Kang SS. Kernohan’s notch phenomenon in chronic subdural hematoma: MRI findings. J Clin Neurosci. 2007 Oct;14(10):989-92.

- Derakhshan I. The Kernohan-Woltman phenomenon and laterality of motor control: fresh analysis of data in the article “Incisura of the crus due to contralateral brain tumor”. J Neurol Sci. 2009 Dec 15;287(1-2):296.

- Safavi-Abbasi S, Maurer AJ, Archer JB, Hanel RA, Sughrue ME, Theodore N, Preul MC. From the notch to a glioma grading system: the neurological contributions of James Watson Kernohan. Neurosurg Focus. 2014 Apr;36(4):E4.

- Derakhshan I. Letter to the Editor: Kernohan’s contributions to neurosurgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;37(4):E22

- Zhang CH, DeSouza RM, Kho JS, Vundavalli S, Critchley G. Kernohan-Woltman notch phenomenon: a review article. Br J Neurosurg. 2017 Apr;31(2):159-166.

- Carrasco-Moro R, Castro-Dufourny I, Martínez-San Millán JS, Cabañes-Martínez L, Pascual JM. Ipsilateral hemiparesis: the forgotten history of this paradoxical neurological sign. Neurosurg Focus. 2019 Sep 1;47(3):E7

- Laaidi A, Hmada S, Naja A, Lakhdar A. Kernohan Woltman notch phenomenon caused by subdural chronic hematoma: Systematic review and an illustrative case. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022 Jun 14;79:104006.

- Beucler N, Cungi PJ, Baucher G, Coze S, Dagain A, Roche PH. The Kernohan-Woltman Notch Phenomenon : A Systematic Review of Clinical and Radiologic Presentation, Surgical Management, and Functional Prognosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2022 Sep;65(5):652-664

- Carrasco-Moro R, Martínez-San Millán JS, Pascual JM. Beyond uncal herniation: An updated diagnostic reappraisal of ipsilateral hemiparesis and the Kernohan-Woltman notch phenomenon. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2023 Oct;179(8):844-865.

- Roy D, Chakravarty A. The Kinetics of Transtentorial Brain Herniation: Kernohan-Woltman Notch Phenomenon Revisited. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2023 Oct;23(10):571-580.

- Carrasco Moro R, Pascual Garvi JM, Vior Fernández C, Espinosa Rodríguez EE, Martín Palomeque G, Cabañes Martínez L, López Gutiérrez M, Acitores Cancela A, Barrero Ruiz E, Martínez San Millán JS. Kernohan-Woltman notch phenomenon: an exceptional neurological picture? Neurologia (Engl Ed). 2024 Oct;39(8):683-693.

- Negrão C, Silva MC, Machado M, Mourato M, Chumbo C, Tomás AR, Coutinho C, Monteiro AC, Matos C. Kernohan-Woltman Notch Phenomenon: A Case of Paradoxical Hemiparesis. Cureus. 2025 Jan 6;17(1):e76987.

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

BSc MD University of Western Australia. Interested in all things critical care and completing side quests along the way

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |