Tuning Fork Tests (Weber and Rinne)

The tuning fork tests — principally the Weber and Rinne tests — remain an essential bedside tool for differentiating conductive from sensorineural hearing loss. These tests are quick to perform and valuable when formal audiometry is unavailable, or as an adjunct to it.

Both tests rely on the phenomenon of bone conduction, wherein vibrations applied to the skull transmit sound directly to the inner ear. This principle was first recognised in the 16th century by anatomist Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia (1510–1580), who noted that vibrations of the teeth produced an auditory sensation — the earliest recorded observation of bone-conducted hearing.

In the Weber test, bone-conducted sound is delivered symmetrically through the skull to both cochleae, and any lateralisation can point to a type of hearing loss. The Rinne test compares air conduction (normal pathway via the tympanic membrane and ossicles) to bone conduction, with the relative performance indicating conductive pathology if bone conduction is perceived as equal or better.

Together, these tests help clinicians rapidly identify the type of hearing impairment:

- Conductive loss: bone conduction ≥ air conduction, Weber lateralises to affected ear.

- Sensorineural loss: air conduction > bone conduction, Weber lateralises to better ear.

Though modern audiometry provides detailed quantitative assessment, tuning fork tests remain indispensable in clinical practice — particularly for acute otological assessment, neurological examinations, and in low-resource settings.

Practical “How to Perform” the tests

Weber Test

- Place vibrating 512 Hz tuning fork on forehead / vertex / chin.

- Ask: “Do you hear the sound equally in both ears, or louder in one?”

- Lateralisation suggests:

- Conductive loss → sound louder in affected ear.

- Sensorineural loss → sound louder in better ear.

Rinne Test

- Place vibrating 512 Hz tuning fork on mastoid until sound no longer heard.

- Immediately hold tuning fork 1 cm in front of external auditory meatus.

- Ask: “Can you hear it again here?”

- Interpretation:

- Air conduction > bone conduction (Rinne positive) → normal or sensorineural loss.

- Bone conduction ≥ air conduction (Rinne negative) → conductive loss.

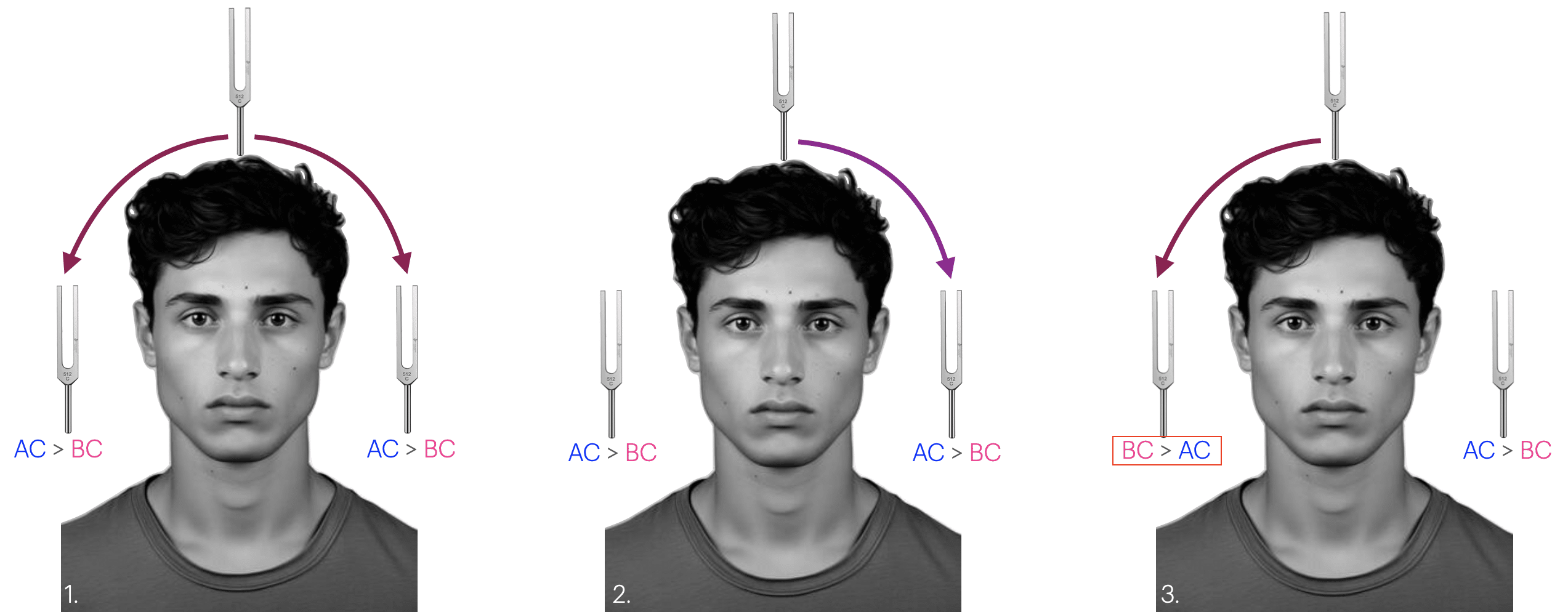

Test interpretation

| Figure | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 1 | Normal results: Rinne test: positive on both sides (Air conduction>Bone Conduction) Weber test: normal referred equally to each ear, indicating symmetrical hearing in both ears with normal middle/outer ear function |

| 2 | Sensorineural deafness in the RIGHT ear: Rinne test: positive on both sides Weber test: referred to the left ear. |

| 3 | Conductive deafness in the RIGHT ear: Rinne test: negative on the right (patients right) (Bone Conduction>Ait Conduction) Rinne test: positive on the left Weber test is referred to the right ear |

History of the Tuning Fork Tests (Weber and Rinne)

1546 – Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia (1510–1580) first describes bone conduction, observing that vibrations applied to the teeth produce sound. “Quia longe majorem similitudinem hoc ossiculum habet cum stapede… audiendo etiam vibrationes dentibus.” – foundational observation for tuning fork tests.

1827 – Caspar Theobald Tourtual (1802-1865) described the occlusion effect in bone conduction using a watch placed on the mastoid — one of the first documented observations of bone-conducted hearing amplification with occlusion.

English physicist and inventor Charles Wheatstone (1802–1875) independently described both the occlusion effect and bone conduction lateralisation in 1827 in his paper Experiments on audition. Anticipated key principles later incorporated in the Weber and Bing tests. Better known for the Wheatstone bridge and stereoscope, but a foundational figure in auditory testing.

1834 – Ernst Heinrich Weber (1795–1878), Leipzig physiologist, publishes De pulsu, resorptione, auditu et tactu. Here he described: (1) the occlusion effect (bone conduction gain on occlusion of the auditory meatus) and (2) the phenomenon of lateralization of bone conduction into the occluded ear.

Weber did not define any test or provide mention of a diagnostic differential between inner ear and middle ear deafness. His observations concerned normal hearing individuals.

Si stylum furcae musicae oscillantis, sonum non nimis acutum edentis, ad dentes apprimimus et os, quantum id fieri potest, labiis et lingua occludimus, auresque simul vel manibus aures appressis, vet digito in meatum auditorium immisso claudimus, furcae sono vehementius percellimur, quam auribus apertis. Si altera auris clausa, altera aperta est, sonum in aure clausa fortiorem quam in aure aperta audimus. Idem turn adeo observamus, si dextram aurem claudimus et stylum furcae musicae oscillantis ad cutim tempora sinistra tegentem apprimimus.

Si cantamus aut loquimur, alteram attrem manu claudentes bac aure sonmn vocis semper vehementiorem percipimus

If we apply a vibrating tuning fork against the teeth and close the mouth as strongly as possible and we close the ears either with the hands or with the finger in the auditory meatus, we perceive the sound of the fork Loader than with open ears. one ear is closed and the other open, we hear the sound louder in the occluded ear than in the open ear. We observe the same when we close the right ear and apply the vibrating fork at the skin of the left temporal bone.

If we sing or speak with one ear occluded by the hand, we always perceive the sound of the voice louder with this ear.

1846 – Eduard Schmalz (1801–1871) is the first to apply bone conduction lateralisation diagnostically. He describes that in conductive loss, the tuning fork is heard better in the affected ear; in sensorineural loss, it lateralises to the better ear. Schmalz provides a complete description of the clinical test (Weber test) as we know it

Die ursprüngliche Idee, eine Stimmgabel als diagnostisches Instrument zur Untersuchung des Ohres einzusetzen, entstand durch die Beobachtung des Leipziger Anatomieprofessors Dr. Ernst Heinrich Weber, dass bei einer Verstopfung eines Ohres (mit dem kleinen Finger) eine Stimmgabel, die mit ihrem Stiel auf eine harte Stelle des Ohres aufgesetzt wird, im verstopften Ohr deutlich besser zu hören ist als im anderen Ohr.

Sind beide Ohren gerund und offen, so Mil man die angeschlagene Stimmgabel beiderseits gleich gut. Sobald man aver den Gehiirgang der einen Seite, mit dem kleinen Finger, oder aid andere Weise, verstopft, so hart man dieselbe, wie sehon erwahnt, auf dem verstopften Ohre jedesmat vier deutlicher, so dass es manchen Personen vorkommt, als horten sie dieselbe nur auf dem verstopften Ohre.

Ist der Gehorgang eines Ohres krankhaft verstopft, z. B. durch angesammelte Haute und Ohrensehmalz, so hart man, sobald sich der Gehornerve desselben nosh in gesundem Zustande befindet, die Stimmgabel auf diesem Ohre deutlicher, als auf dem anderen. Verstopft man such das andere Ohr, so wird dieselbe dann beiderseits gleithmassig gehort. Dasselbe Verhaitniss finder such statt, wenn bet gesundern Zustande des Nerven sclbst die Ohrtrompete oder die Trommelhohle des einen Ohres, z. B. durch Bluterguss, durch abgelagerte katarrhalische, rheumatische oder a. dergl. Massen, verstopft ist, der Gehargang mag an der Verstopfung Theil nehmen oder nicht.

Ist hingegen der Geharnerve eines Ohres von der Krankheit ergriffen, so hart man die angeschlagene Stimmgabel jedesmal auf dem Ieidenclen Ohre weniger gut, als ad dem gesunden, und die Verstopfung des gesunden oder kranken Ohres macht in dieser I-linsicht durchaus keinen Unterschied.

The initial idea of using a tuning fork as a diagnostic tool for examining the ear was prompted by the observation made by Dr. Ernst Heinrich Weber, Professor of Anatomy in Leipzig, that if one ear is blocked (with the little finger), a tuning fork placed on a hard part of the head can be heard much better in the blocked ear than in the other.

If both ears are open, the sound of the tuning fork can be heard equally well on both sides. As soon as the ear canal is closed on one side, the tuning fork can be heard much more clearly in the blocked ear.

If one ear canal is pathologically blocked, the tuning fork can be heard more clearly in that ear than in the other, provided the auditory nerve is still healthy. If the other ear is also blocked, hearing is equally good in both ears. The same situation also occurs if, while the auditory nerve is healthy, the Eustachian tube or eardrum in one ear is blocked.

If, however, the auditory nerve of one ear is affected by disease, the sound of the tuning fork is always less effective in the affected ear than in the healthy one, and the blockage of the healthy or diseased ear makes absolutely no difference in this respect.

1842 – Austrian physician and early otologist Franz Polansky (1810/11–1887) described the full Rinne test principle in 1842 in Grundriss zu einer Lehre von den Ohrenkrankheiten, over a decade before Rinne’s 1855 publication. Polansky’s work on air versus bone conduction as a diagnostic tool was later largely overlooked, but recognised retrospectively as the earliest known description of the method now called the Rinne test.

1855 – Heinrich Adolf Rinne (1819–1868), Göttingen general practitioner, publishes Beiträge zur Physiologie des menschlichen Ohres. He described 22 experiments on hearing and describes test comparing air vs bone conduction (Rinne test)

Versuch I. Ein leicht anzustellender Versuch zeigt uns, in welchem Grade die Leitung durch die Schädelknochen, selbst für Töne, die durch Schwingungen eines festen Körpers entstehen und unmittelbar auf das Skelett übertragen werden, hinter der normalen Leitung durch Luft, Trommelfell, u.s.w. zurücksteht. Ich stemme eine durch Anschlagen zum Tönen gebrachte Stimmgabel gegen die oberen Schneidezähne, und lasse sie in dieser Lage bis zu dem Momente, wo der in Anfange sehr klare Ton für mich unhörbar wird. Jetzt bringe ich die Stimmgabel vor das äussere Ohr, und höre aufs Neue den Ton mit grosser Intensität. Erst nach geraumer Zeit verklingt derselbe auch hier. Bei allen Personen mit gesundem Ohre, bei denen ich diesen Versuch wiederholte, war der Erfolg derselbe.

Anmerkung. Es lässt sich dieser Versuch auch zur Sicherung der Diagnose bei nervöser Schwerhörigkeit anwenden. Denn hat derselbe bei Schwerhörigen ungeachtet ihrer Krankheit denselben Erfolg, wie bei Gesunden, so schliessen wir mit Recht, dass das Verhältniss der Leitungsfähigkeit der Kopfknochen und der complicirten acustischen Apparate das normale is, also der Hörnerv krank sein muss. Hört dagegen der Patient den durch die Kopfknochen zugeleiteten Ton eben so lange oder gar länger, als den auf dem normalen Wege zugeführten, so schliessen wir auf eine Krankheit eines der leitenden Apparate

Experiment I. An simple experiment demonstrates the degree to which conduction through the skull bones lags behind normal conduction through the air. I press a tuning fork, which I have struck, against my upper incisors and leave it in this position until the moment when the tone becomes inaudible to me. I then bring the tuning fork to the external ear to once again hear the tone with great intensity. Only after some time does it fade away here as well. This occured in all persons with healthy ears on whom I repeated this experiment.

Note: This experiment can also be used to confirm the diagnosis of sensorineural deafness. If it has the same effect on hearing-impaired individuals, regardless of their illness, as it does on healthy individuals, then we rightly conclude that the relationship between the conduction capacity of the skull bones and the complex acoustic apparatus is normal, and therefore the auditory nerve must be diseased. If, on the other hand, the patient hears the sound transmitted through the skull bones just as long or even longer than the sound transmitted through the normal pathway, then we conclude that one of the conducting apparatuses is diseased.

1880 – August Lucae (1835–1911) revives the Rinne test and introduces terms Rinne positive and Rinne negative (1882)

1885 – Dagobert Schwabach (1846–1920) publishes detailed evaluation of tuning fork tests. Introduces the Schwabach test (duration of bone conduction vs normal ear). Also confirms Rinne test’s clinical value “Dieser Versuch bietet… einen nicht zu unterschätzenden Anhaltspunkt für die Differentialdiagnostik.”

The Schwabach test measures the duration of bone-conducted sound in comparison with that perceived by an examiner with normal hearing. It complements the Rinne and Weber tests in differentiating conductive from sensorineural hearing loss. Though similar techniques were noted earlier by Schmalz (1849), Lucae (1880), and Emerson (1884), Schwabach’s systematic study brought the test into widespread clinical use.

1891 – Albert Bing (1847–1924) formalises the Bing test based on the occlusion effect for conductive loss.

20th century – Tuning fork tests incorporated into standard bedside and emergency otologic examination worldwide. Remain useful adjunct to pure tone audiometry.

Associated Persons

- Giovanni Filippo Ingrassia (1510–1580): First description of bone conduction.

- Charles Wheatstone (1802–1875): First published observation of bone conduction lateralisation

- Caspar Theobald Tourtual (1802-1865): Early description of bone conduction lateralisation

- Ernst Heinrich Weber (1795–1878): Early observation of bone conduction lateralisation

- Eduard Schmalz (1801–1871): First clinical application of tuning fork lateralisation.

- Franz Polansky (1810/11–1887): First description of air vs bone conduction comparison.

- Heinrich Adolf Rinne (1819–1868): Eponymous description of Rinne test.

- August Lucae (1835–1911): Clinical popularisation of Rinne test.

- Dagobert Schwabach (1846–1920): Systematic study of tuning fork tests; introduction of Schwabach test.

- Albert Bing (1847–1924): Formalisation of Bing (occlusion) test.

References

Historical references

- Wheatstone C. Experiments on audition. The Quarterly Journal Of Science, Literature, And Art 1827; 22: 67-72

- Tortual CT. Die Sinne des Menschen in den wechselseitigen Beziehungen ihres psychischen und organischen Lebens: ein Beitrag zur physiologischen Aesthetik. Münster : F. Regensberg, 1827.

- Weber EH. De pulsu, resorptione, auditu et tactu. Annotationes anatomicae et physiologicae, auctore. 1834

- Schmalz E. Erfahrungen über die Krankheiten des Gehöres und ihre Heilung. Leipzig, 1846.

- Schmalz E. Mémoire sur l’emploi de la fourchette tonique ou du diapason, pour distinguer une dureté d’ouïe nerveuse de celle qui est causée par une obstruction. 1849

- Polansky F. Grundriss zu einer Lehre von den Ohrenkrankheiten. Vienna, 1842.

- Rinne A. Beiträge zur Physiologie des menschlichen Ohres. Vierteljahrschrift für die Praktische Heilkunde. 1855; 12(1): 71-123

- Rinne A. Beiträge zur Physiologie des menschlichen Ohres. Zeitschrift für rationelle Medicin, 1864; 24(1): 12-64

- Lucae A. Buchbesprechung. Archiv für Ohrenheilkunde. 1880; 16: 88

- Lucae A. Zur physikalischen differentiellen Diagnostik zwischen Erkrankung des schalleitenden Apparates und Nerventaubheit. Archiv für Ohrenheilkunde. 1882; 19: 73-75

- Schwabach D. Über den Werth des Rinne’schen Versuches für die Diagnostik der Gehörkrankheiten. Zeitschrift für Ohrenheilkunde. 1885; 14: 16-48

- Bing A. Ein neuer Stimmgabelversuch; Beitrag zur Differentialdiagnostik der Krankheiten des mechanischen Schallleitungs- und des nervösen Hörapparates. Wiener medizinische Blätter. 1891; 14(41): 637-638.

- Bing A. Zur Analyse des Weber’schen Versuchs. Wiener Medizinische Presse. 1891; 32(9): 330-332

Eponymous term review

- Huizing EH. The early descriptions of the so-called tuning fork tests of Weber and Rinne. I. The “Weber test” and its first description by Schmalz. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1973;35(5):278-82.

- Huizing EH. The early descriptions of the so-called tuning-fork tests of Weber, Rinne, Schwabach, and Bing. II. The “Rhine Test” and its first description by Polansky. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1975;37(2):88-91.

- Huizing EH. The early descriptions of the so-called tuning-fork tests of Weber, Rinne, Schwabach, and Bing. III. The development of the Schwabach and Bing tests. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1975;37(2):92-6.

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

MBBCh Cardiff University School of Medicine. BSC (Hons) Medical Microbiology Leeds University. I am a current ED RMO at the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth hoping to pursue a career in ENT surgery.

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |