Quincke’s Triad

Quincke’s Triad: right upper quadrant abdominal pain (biliary colic), gastrointestinal bleeding, and jaundice as the hallmark presentation of hemobilia (bleeding into the biliary tract).

This triad is considered pathognomonic for hemobilia (bleeding into the biliary tree) and is most commonly associated with hepatic artery aneurysm rupture, iatrogenic trauma, or hepatic tumours. The complete triad is present in only 22% to 35% of hemobilia cases making partial presentations more typical.

Though classically linked to ruptured hepatic artery aneurysm, modern understanding recognizes a broader set of causes.

- Iatrogenic interventions: Including liver biopsy, cholecystectomy, percutaneous biliary drainage, or ERCP. Account for up to 65% of hemobilia cases due to vascular injury and pseudoaneurysm formation

- Trauma: Occurs in about 2.5% of accidental and 3–7% of incidental hepatic injuries

- Vascular malformations: Such as aneurysms or arteriovenous fistulae, including from splenic (most common), hepatic, or gastroduodenal arteries

- Malignancy and infection: Tumours (e.g., hepatocellular carcinoma), abscesses, or inflammation eroding into vessels

Mortality and Prognosis:

- In cases of hepatic artery aneurysm causing hemobilia, rupture carries a mortality of ~40%

- Hemobilia generally demands urgent attention due to life-threatening haemorrhage potential.

Trends in Modern Practice:

With the rise of invasive hepatobiliary procedures, the incidence of hemobilia has increased and iatrogenic causes now predominate.

Transarterial embolisation has largely supplanted surgery as the first-line treatment, offering high success and lower morbidity

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Triad completeness | 22%–35% of hemobilia cases |

| Iatrogenic causes | ~65% (e.g., liver biopsy, cholecystectomy, ERCP) |

| Trauma-related hemobilia | 2.5% of accidental, 3–7% of incidental injuries |

| Mortality (aneurysm rupture) | ~40% |

| Best initial intervention | Transarterial embolisation (~90% success) |

Google Ngram analysis suggests that the eponym “Quincke’s Triad” emerged in the English literature in the 1970s, aligning with its increased clinical relevance amid advances in hepatobiliary and interventional disciplines.

History of Quincke’s Triad

1654 – English physician and anatomist Francis Glisson (1597–1677) published Anatomia Hepatis. In Chapter IX, De Hepatis continuitate, he noted that the bile ducts could transmit substances other than bile into the intestines, including blood, especially following liver trauma. He hypothesised that liver contusion might result in vomiting or defecation of blood, as bile passages could help expel excess blood via the intestines.

…porum biliarem (magno aegroti commodo) partem sanguinis, quem iecur opprimit, in se recipere et ad intestina deducere – Glisson 1654

…the biliary pores (to the great advantage of the patient) receive into themselves the part of the blood which the liver oppresses and conduct it to the intestines – Glisson 1654

Glisson also documented a case of hemobilia secondary to penetrating trauma, describing a duel between two noblemen. One sustained a deep epigastric stab wound, and although he vomited daily for a week, no blood appeared in the vomitus. Instead, he passed large quantities of clotted blood per rectum, and died a week later. On autopsy, blood was found in the abdomen but not in the stomach

1765 – Giovanni Battista Morgagni (1682–1771) in Epistola Anatomico-Medica XXXVI from Opera Omnia, Morgagni recorded a pathological case of biliary bleeding. In Case 6 (Tome IV, p. 57–58), he described a hepatic abscess that ruptured into the biliary tract, leading to obstruction by blood clots with potential bile duct dilatation.

1777 – Antoine Portal (1742–1832) in Sur quelques Maladies du Foie, quon attribue à d’autres organes, described treating a patient with liver inflammation who vomited and passed through the stool significant amounts of dark, clotted blood. On autopsy, the liver was found doubled in size, blackened, abscessed with the bile ducts, gallbladder, and small intestine filled with blood and pus.

Une altération du foie, dont M. Morgagni a fait mention, presque inconnue des autres Médecins…sont les hémorragies de ce viscère par le canal cholédoque…les conduits biliaires & les intestins grêles pleins de sang

Je fus chargé de donner mes soins à une personne (un Domestique de Madame fa Marquise de Cambis)…par l’ouverture de son corps, que la maladie avoit eu son siége dans le foie…les canaux hépatique & cystique, la vésicule du siel, le canal cholédoque & les intestins grêles étoient pleins de fang & de pus. – Portal 1777

An alteration of the liver, which Mr. Morgagni mentioned, almost unknown to other physicians…is the hemorrhages of this viscus through the bile duct…the bile ducts and small intestines full of blood.

I was charged with treating a person (a servant of Madame the Marquise de Cambis)…by opening his body, it was found that the disease had its seat in the liver…the hepatic and cystic ducts, the gallbladder, the bile duct, and the small intestines were full of blood and pus. – Portal 1777

1871 – Heinrich Irenaeus Quincke (1842–1922) published a detailed case of hepatic artery aneurysm rupture leading to bleeding into the biliary tree in Ein fall von Aneurysma der Leberarterie. He associated three cardinal features now recognised as Quincke’s triad:

- Right hypochondrium pain

- Jaundice

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (haematemesis and melena)

Die Krankheit begann…mit Kolik, Erbrechen und etwas Blutbeimengung im Stuhl… Der Kranke war bleich, hatte leichten Ikterus… gegen Abend Bluterbrechen…Wiederholte Blutungen aus dem Magen und schwarzer Stuhl wechselten mit Gelbsucht und Schmerzanfällen im rechten Hypochondrium – Quincke 1871

The illness began…with colic, vomiting and some blood in the stool…The patient was pale, had slight jaundice…in the evening he vomited blood…Repeated bleeding from the stomach and black stools alternated with jaundice and attacks of pain in the right hypochondrium – Quincke 1871

1879 – (Charles) Eugène Quinquaud (1841–1894) published Les affections du foie. Des hémorrhagies des voies biliaires outlining the diverse origins (trauma, inflammation, tumour, and haemorrhagic diathesis) of haemorrhage affecting the biliary tract. He introduced the term l’angèiocholite hémorragique to describe patients suffering jaundice, intense abdominal pain mimicking biliary colic, and gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Autopsies revealed biliary ducts filled and distended with blood clots, whilst the portal vessels remained unaffected.

I studied hemorrhages of various causes… and I demonstrate the existence of a new lesion of the bile ducts, l’angèiocholite hémorragique causing jaundice accompanied by violent pains simulating biliary colic; later melena and hematemesis… the ducts were distended and filled with blood clots of various age; the portal vessels were free.

1895 – Bruno Mester (1863–1895) published Das Aneurysma der Arteria hepatica including the case of a 42 year old coachman who was kicked in the abdomen by a horse. He outlined the cardinal triad of intense biliary colic, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, and jaundice.

Mester illustrated the morphology and clinical implications of hepatic artery aneurysms, identifying their potential to rupture into the biliary tract and advocated ligation of the hepatic artery in life-threatening haemorrhage.

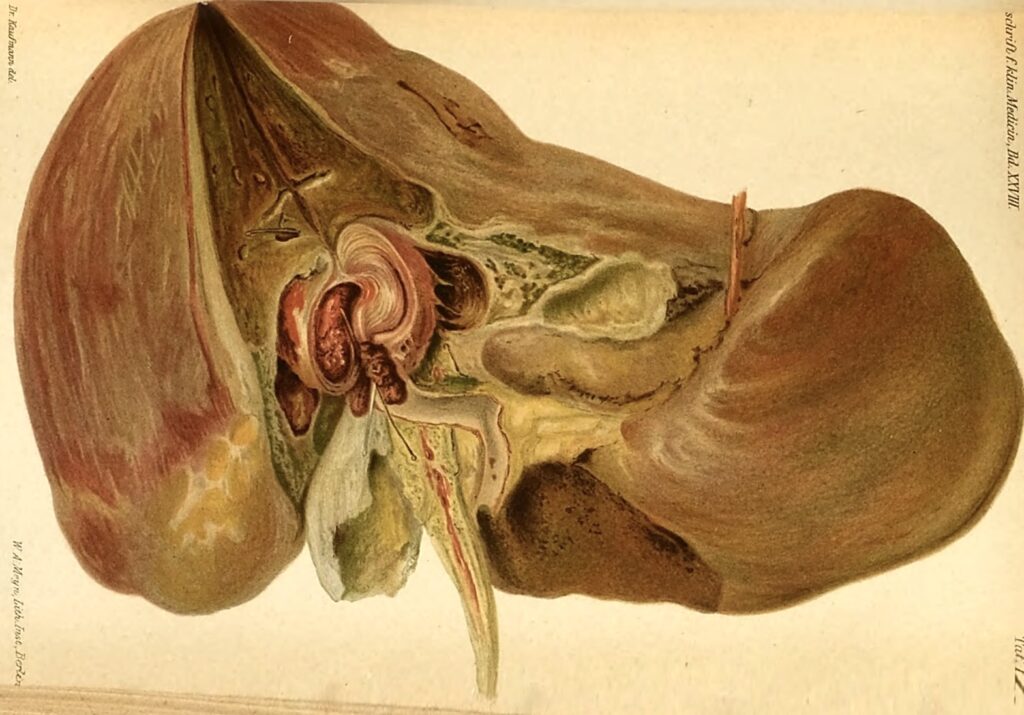

The figure depicts the hepatic artery aneurysm filled with layered clots, as it protrudes into the cavernous bile duct, having been penetrated by a fortunate longitudinal incision. A finer, short probe is inserted into the hepatic artery and leads into the lumen of the aneurysmal sac; the longer and thicker probe leads into the trunk of the hepatic artery behind the aneurysm. The liver tissue, just beneath the diaphragm, which is fused to the liver surface, is severely icteric and scarred at the level of the aneurysm. The hepatic artery crosses the incision of the hepatic duct. The gallbladder is split; one fragment lies on the quadrate lobe, the other above the right liver lobe.

1948 – Philip Sandblom (1903–2001) introduced the term hemobilia in his article Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia drawing attention to post-traumatic bleeding into the biliary system. His initial pride in having named a syndrome was undercut when informed that haima (Greek for blood) and bilis (Latin for bile) made ‘hemobilia’ a linguistic mongrel. To which he replied:

When haima is added to bilis, the result is an unfortunate mixture, even in the clinical sense.

1950s–1960s Introduction of selective hepatic angiography by Linton and colleagues allowed accurate diagnosis, localisation and treatmentof bleeding sources.

1972 – Sandblom published his monograph Hemobilia in which he provided a comprehensive review of 116 historical and clinical cases and credited Quicke for both the typical triad of biliary tract haemorrhage and the characteristic features of coaguli formed in the biliary tract.

1975 – Eddy Davis Palmer, (1917-2010) first documented use of the term Quincke’s triad of hemobilia in the second edition of his textbook Practical Points in Gastroenterology as:

Quincke’s triad of hemobilia consists of GI hemorrhage, biliary colic, and jaundice.

References

Historical references

- Glisson F. De Hepatis continuitate. In: Anatomia hepatis, 1654: 98-108 [Stab wound through liver. First recorded case of hemobilia. Discussion on, pathogenesis]

- Morgagni G. Epistola Anatomico-Medica XXXVI. Opera Omnia, Tome IV: 57–58) [Liver abscess. Biliary tract distension due to haemorrhagic obstruction]

- Portal A. Sur quelques Maladies du Foie, quon attribue à d’autres organes ; à fur des Maladies dont on fixe ordinairement le fiége dans le Foie , quoiqu’il ny Joit pas. Histoire de l’Académie royale des sciences, avec les mémoires de mathématique et de physique 1777: 601-613 [Diagnosis before death of patient. Autopsy confirms hemobilia]

- Stokes W. Researches on the diagnosis and pathology of aneurism. Dublin journal of medical and chemical science 1834; 5: 400-440 [Aneurysm bursting into liver. Dispute dispute over pathogenesis]

- Jackson JBS. Aneurism of the hepatic artery bursting into the hepatic duct. Medical Magazine, Boston, 1834; 3(4): 115-117. [First case of Hemobilia in America]

- Owen HK. Case of lacerated liver. London medical gazette, 1848; 7: 1048-1054 [Traumatic hemobilia early case]

- Lebert H. CCCLXXXVI. — Anéurysme de l’artère hépatique, avec rupture dans la vésicule du fiel et hématémèse abondante suivie d’épuisement et de mort. (PI. CXXVII, fig. 6-8.). Traité d’anatomie pathologique générale et spéciale, 1861; 2: 322-333

- Quincke H. Ein fall von Aneurysma der Leberarterie. Berliner Klinische Wochenschrift 1871; 8: 349-352 [Hepatic artery aneurysm. Described triad of biliary tract haemorrhage]

- Quinquaud E. Les affections du foie. Des hémorrhagies des voies biliaires. Paris, 1879 [Extrait de ‘La Tribune médicale‘ 1875; 8: 543 and 1877]

- Mester B. Das Aneurysma der Arteria hepatica. Zeitschrift für klinische Medizin, 1895; 28: 93-112. [Liver haemorrhage. Describes inappropriate operation failing to recognise hemobilia]

- Lichtman, S.S. Gastro-intestinal bleeding in disease of the liver and biliary tract. American Journal of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition 1936; 3: 439–445

- Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia. Surgery. 1948 Sep;24(3):571-586. [Traumatic Hemobilia]

- Sandblom P. Hemobilia (biliary tract hemorrhage); history, pathology, diagnosis, treatment. 1972 [Credits Quincke for the naming of the triad]

- Palmer ED. Practical Points in Gastroenterology. 1975 (2e): 147 [First published use of Quincke’s triad]

Eponymous term review

- Kerr HH, Mensh M, Gould EA. Biliary tract hemorrhage; a source of massive gastro-intestinal bleeding. Ann Surg. 1950 May;131(5):790-800.

- Sandblom P. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage through the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1970 Jan;171(1):61-6.

- Harlaftis NN, Akin JT. Hemobilia from ruptured hepatic artery aneurysm. Report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Surg. 1977 Feb;133(2):229-32.

- Curran FT, Taylor SA. Hepatic artery aneurysm. Postgrad Med J. 1986 Oct;62(732):957-9.

- Belfonte, Cassius MB, BS; Sanderson, Andrew MD, FACG; Dejenie, Freaw MD. Quincke’s Triad: A Rare Complication of a Common Outpatient Procedure. American Journal of Gastroenterology 106():p S277, October 2011

- Berry R, Han JY, Kardashian AA, LaRusso NF, Tabibian JH. Hemobilia: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Liver Res. 2018 Dec;2(4):200-208.

- Jamtani I, Nugroho A, Irfan W, Fadli M, Saunar RY, Widarso A, Poniman T. Revisiting Quincke’s Triad: A Case of Idiopathic Hepatic Artery Aneurysm Presenting with Obstructive Jaundice. Ann Vasc Surg. 2021 Feb;71:536.e1-536.e4.

- Patil NS, Kumar AH, Pamecha V, Gattu T, Falari S, Sinha PK, Mohapatra N. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm-a rare complication of acute cholecystitis: review of literature. Surg Endosc. 2022 Feb;36(2):871-880.

- Schütz ŠO, Rousek M, Pudil J, Záruba P, Malík J, Pohnán R. Delayed Post-Traumatic Hemobilia in a Patient With Blunt Abdominal Trauma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Mil Med. 2023 Nov 3;188(11-12):3692-3695.

- Ahmed M, Saeed R, Woodward C, Nguyen K, Auda D. Quincke’s Triad and Cystic Artery Pseudoaneurysm. Cureus. 2025 Jan 18;17(1):e77627.

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

Physician in training. German translator and lover of medical history.