Elbow Dislocation

Elbow dislocations constitute 10% to 25% of all injuries to the elbow. The elbow is one of the most commonly dislocated joints in the body, with an average annual incidence of acute dislocation of 6 per 100,000 persons. Among injuries to the upper extremity, dislocation of the elbow is second only to dislocation of the shoulder.

Simple or Complex

Simple dislocations are described by the direction of the dislocated ulna. Posterior or posterolateral displacement of the ulna relative to the distal humerus is the most common simple dislocation with approximately 90% occurring this way (see image ). Rarer injuries include lateral and anterior displacements of the forearm.

When larger intra-articular fractures of the radial head, olecranon, or coronoid process occur with elbow dislocation, the injury is termed a complex dislocation. Complex dislocations are much less common than simple dislocations. The risk of recurrent or chronic instability and posttraumatic arthrosis is increased significantly with complex dislocation.

Anatomy

The elbow joint is one of the most inherently stable articulations. This stability is provided by the osseous and articular components with the shape and contour of the ulnohumeral articular surface providing anterior-posterior stability, varus/valgus, and rotatory stability. The capsuloligamentous components, which include the medial and lateral collateral ligaments and joint capsule, provide further stability by completing a structural ring about the elbow joint. Disruption of this ring is leads to elbow dislocation.

Finally the musculotendinous components, which include the muscles crossing the elbow joint, also contribute to the stability.

Evaluation

Patients present following a traumatic injury with swelling and deformity about the elbow. The mechanism of injury is usually a fall onto an outstretched hand.

TIP: Elbow dislocation is sometimes confused with a supracondylar fracture. The two may be distinguished clinically by palpating for the equilateral triangle formed by the olecranon and epicondyles. This will be undisturbed in supracondylar fractures but distorted in elbow dislocations.

Neurovascular injury is uncommon, but should always be sought. Clinical evaluation should include median and ulna nerve function. Damage to the brachial artery can be assessed by palpating for a radial pulse.

After a complete examination, AP and lateral X-Rays of the elbow should be examined to determine the direction of the dislocation and to identify any associated fractures.

Management

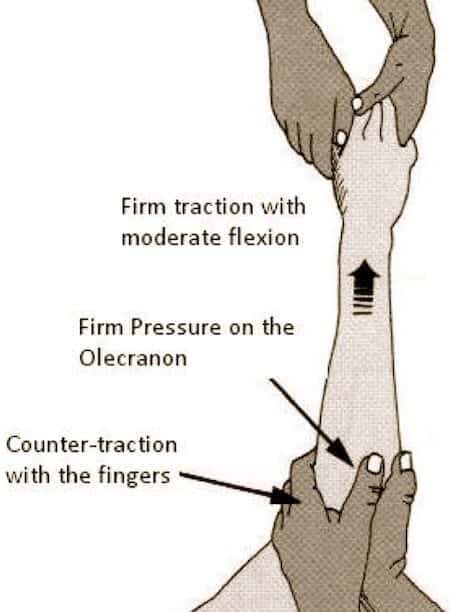

Reduction can usually be carried out in the emergency department. It requires adequate muscular relaxation and appropriate analgesia. A fair amount of force is often required. Reduction may be achieved by correction of the medial or lateral displacement followed by strong traction on the forearm in the line of the limb. The arm may enlocate at this stage with a characteristic and satisfying reduction ‘clunk’. If not, firm pressure is applied posteriorly to the olecranon to bring it distally and anteriorly around the humeral trochlea. Traction should be maintained with the arm in moderate flexion, using counter-traction with the fingers. (see fig) Again a palpable ‘clunk’ will confirm reduction. Palpation should ensure the equilateral triangle formed by the olecranon and epicondyles is present.

TIP: After reduction, the elbow should be taken through a range of motion to evaluate joint stability. The elbow should be slowly extended and the angle at which tendency to redislocation occurs should be recorded. Most dislocated elbows are unstable to valgus stress (best tested in pronation to lock the lateral side).

X-Rays should then be performed in two planes, AP and lateral to ensure the reduction is concentric. Widening of the joint space may indicate entrapped osteochondral fragments. These patients should be referred to Orthopaedics for surgical debridement.

Note: Although X-Rays reveal periarticular fractures in 12% to 60% of cases, surgical exploration documents unrecognized osteochondral injuries in nearly 100% of acute elbow dislocations. Fortunately, the vast majority do not require operative intervention.

If the reduction is concentric and the joint is stable, the elbow should be splinted in 90 degrees of flexion. Patients should be followed up in 3-5 days with repeat X-rays to check reduction.

Complex dislocations

Complex elbow dislocation consists of both ligamentous and bony injuries. When one of the osseous or articular component structures of the elbow is disrupted, the risk of recurrent instability and arthrosis is greatly increased. Early mobilization of simple dislocations after closed reduction is associated with low risk of redislocation. These injuries, are more difficult to treat, and often have poorer results than simple dislocation. Fortunately they are much less frequent.

The radial head and coronoid process are the most commonly fractured structures in these injuries. Other structures that can be damaged include: medial and lateral collateral ligaments; medial and lateral condyles/epicondyles; transolecranon fractures and; posterior Monteggia fractures.

This disrupts the structural ring which provides stability to the elbow joint (see figure above). If there is evidence of disruption of one component of the ring, a second disruption is likely.

Note: The terrible triad consists of dislocation with associated radial head and coronoid process fracture.

Complex dislocations should have the same initial treatment- with clinical evaluation and reduction- as simple dislocations. They should all be referred to the inpatient Orthopaedic Surgery team for ongoing management, as they will require surgical repair.

Peer Review: Dr W G Blakeney

[cite]

Trauma Library

Injury database