Fever, Arthralgia and Rash

aka Tropical Travel Trouble 010

You are an ED doc working in Perth over schoolies week. An 18 yo man comes into ED complaining of fever, rash a “cracking headache” and body aches. He has just hopped off the plane from Bali where he spent the last 2 weeks partying, boozing and running amok. He got bitten by “loads” of mosquitoes because he forgot to take insect repellent.

On examination he looks miserable, temp 39.8 °C, HR 115, BP 108/60, blanching maculopapular rash over his face, thorax, and flexor surfaces.

Q1. What could this be?

Answer and interpretation

Acute febrile illness in the returned traveller can be a number of diagnoses (not exhaustive):

- Bacterial: strep throat, leptospirosis, toxic shock syndrome, rickettsia, typhoid, melioidosis, scarlet fever and meningitis.

- Viral: Fifth disease, enterovirus, hepatitis, zika, Chikungunya, Roseola, EBV, HIV seroconversion, West Nile virus, influenza, adenovirus, measles and Rubella.

- Parasitic: malaria

- Non infectious: ITP, Acute leukaemia, drug reaction and Kawasaki in the young.

Due to fact this is a tropical post the most likely culprit is an arbovirus (any disease transmitted by arthropods – insects).

There are three main groups of arbovirus presentations in humans:

- FAR (Fever, arthralgia and rash – as in our patient),

- CNS (central nervous system symptoms most predominantly an encephalitis e.g. Japanese encephalitis),

- VHF (viral hemorrhagic fever e.g. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever).

While it can be overwhelming the number of possibilities on presentation, a thorough travel history, history of presenting illness and examination will help you to narrow down your testing (yes this is why the ID team get you to order a raft of investigations as there is no other way). Travel health Pro is an excellent resource for looking up what travellers are at risk for including outbreaks and news for that country (I see Australia has a highly resistant Gonorrhoea at the moment!)

See the diagram below to narrow down your arbovirus differential.

Q2. What is Dengue Fever and how do you contract it?

Answer and interpretation

Dengue is the most common mosquito borne viral illness in humans. Derived from the Swahili word “dinga” which likely influenced the spanish word “dengue” meaning fastidious or careful which would describe the gait of someone with the bone pain of dengue fever.

Dengue viruses are single-stranded RNA viruses that belong to the genus Flavivirus.

The

dengue virus comprises of four distinct serotypes (DEN-1, DEN-2, DEN-3

and DEN-4). Among them the “Asian” serotypes of DEN-2 and DEN-3 are

frequently associated with severe disease accompanying secondary dengue

infections. This may be because these strains are more virulent or

antibodies against one dengue virus serotype (from a previous infection)

enhance the entry of a second dengue virus into macrophages, leading to

a more severe infection. The latter theory has made some scientists

nervous about creating a vaccine only covering one strain.

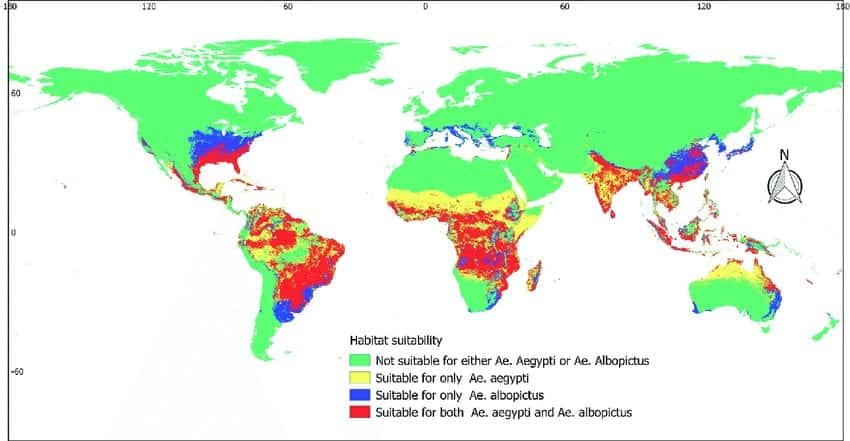

Dengue virus is transmitted by the bite of the female Aedes genus mosquito found in tropical and sup tropical parts of the world. They are the same mosquitoes that transmit Zika virus, Yellow Fever and Chikungunya but are different to the mosquitoes that transmit malaria (Anopheles).

Annoyingly Aedes mosquitos feed during the day whereas Anopheles mosquitos feed at night. Hence the usual methods of mosquito nets +/- insecticide impregnation fail. Approximately 40-50% of the world’s population are at risk of contracting the virus.

The disease mainly affects children and travellers as adults develop immunity to the serotype in their area.

Q3. What is the incubation period for Dengue Fever?

Answer and interpretation

The incubation period for dengue fever is 3-14 days; usually 4-7 days – just long enough for a week in Bali!

Consider differentials if someone presents 2 weeks or more after returning from an endemic area.

Q4. How does Dengue Fever present clinically?

Answer and interpretation

Dengue Fever has 3 stages of infection:

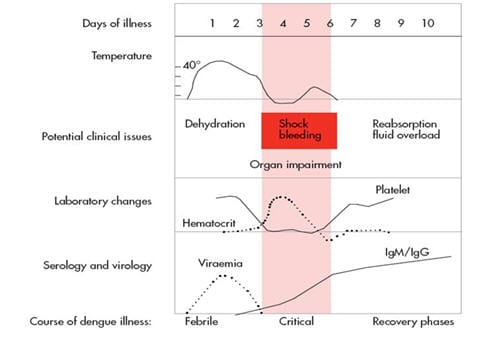

1. Febrile phase last 2-7 days (viraemic phase):

- Dengue presents with sudden onset high fever (often up to 40.5°) with associated chills, severe ‘breakbone’ myalgia, arthralgia, retro-orbital pain and headaches. Additional GI symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting and loose stool are common).

- On day 2-5 after fever onset, a blanching maculopapular rash develops over the face, trunk and flexor surfaces. This rash usually last 2-3 days. In addition petechiae and ecchymoses may also be present.

- A second measles-like (morbilliform) rash may appear within 1-2 days of defervescence (abatement of fever), this rash spares the palms and soles, and occasionally desquamates.

2. Critical (plasma leak) phase – riskiest time for developing complications:

- If the temperature drops below 37.5 celsius during the first 3 to 7 days, some patients may experience an increase in capillary permeability as well as increased haematocrit levels.

- This phase lasts 24 to 48 hours and can be associated with bleeding (epistaxis, vaginal, gastrointestinal, gums).

- The mechanism is not well understood but in those patients who have greater capillary permeability they will rapidly develop tissue hypo perfusion and hypovolaemic shock. Pleural effusions, ascites, nephropathy and myocardial injury are all possibilities during this phase.

3. Recovery phase – where there is gradual reabsorption of the leaked fluid from the extravascular to the intravascular space:

- The reabsorption takes 48 to 72 hours but some patients may develop a late appearance rash called “white isles on a red sea” accompanied by generalised parities.

- Sinus bradycardia can also occur during this stage.

- Full blood counts, haemocrit and platelets also recover.

Q5. What is the modified dengue severity classification?

Answer and interpretation

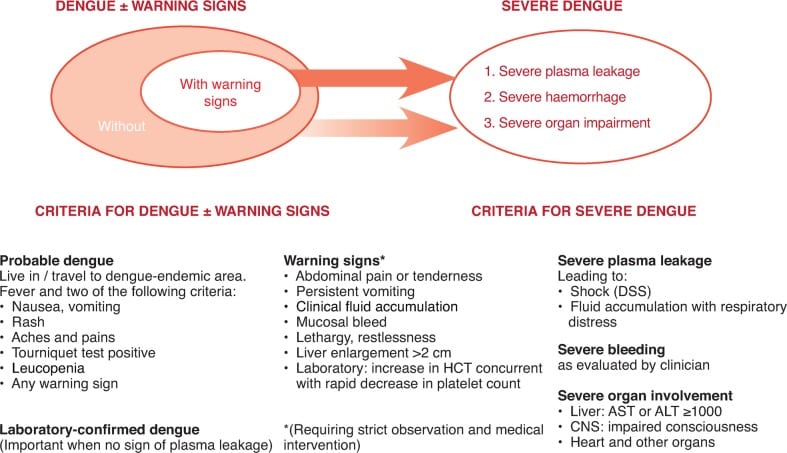

Previously Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS) and Dengue Haemorrhagic Fever (DHF) where by DSS, was an acute increase in vascular permeability leads to extensive third spacing and plasma volume loss with associated clinical shock. If untreated it may lead to metabolic acidosis, cellular hypoxia and death. The hallmark features of DHF are vascular changes, thrombocytopaenia and coagulation disorders (DIC). A rising haematocrit with continually dropping platelets suggests the onset of shock.

Based on the DENCO study and multiple round the table discussions a new criteria was set to include ‘Dengue with warning signs’ as these patients often had a real possibility of progressing to severe disease:

Q6. How do you diagnose Dengue Fever?

Answer and interpretation

Clinically if no tests are available (see diagram above), patient travelled through an at risk area with two symptoms. Can include a positive tourniquet test(sensitivity 58% and specificity 71%) as one of the symptoms.

- 10 or more petechiae in a 1 square inch on the patients arm after 2 mins with a BP cuff inflated to their mid DBP and SBP. See how to do one here.

Bloods for dengue NS1 antigen +/- PCR and dengue serology. IgM and IgG will only start becoming positive after day 5.

Other tests to perform include:

- Full blood count – leucopenia and thrombocytopenia are common. Monitor for a low haematocrit.

- Coagulation studies – detect DIC.

- LFT/albumin/protein – detect hypoproteinaemia; elevated AST/ALT.

- CXR and Ultrasound if effusions and ascites are possible in patients in the critical phase.

Q7. How do you treat Dengue Fever?

Answer and interpretation

Dengue is usually a self-limiting illness.

- Treatment is entirely supportive – fluids, analgesia, rest.

- Avoid aspirin, NSAIDS, steroids, antibiotics and oral anticoagulants.

- Patients who can tolerate adequate volume of oral fluids, passing urine every 6 hours and have no warning signs can be managed as an outpatient with follow up blood tests and a check for any warning signs every 24-48 hours after defervescence. Patients should be advised to return for medical attention if they develop any warning signs.

Dengue Guidelines:

Low risk Dengue patient treatment guidelines:

Patients who have Dengue without warning signs but have an associated disorder or social risk should be managed as an inpatient (e.g. social isolation, far from medical centre, pregnant, under 1 year of age, over 65 years, obesity, HTN, diabetes, asthma, renal failure, haemolytic disease, chronic liver disease, peptic ulcers and the use of anticoagulants).

Dengue with warning signs require inpatient monitoring +/- IV fluids along with close haemtocrit, blood count, platelet and electrolyte monitoring. IV fluids should be titrated along normal parameters of blood pressure, urine output, conscious state and an awareness of third space losses/complications.

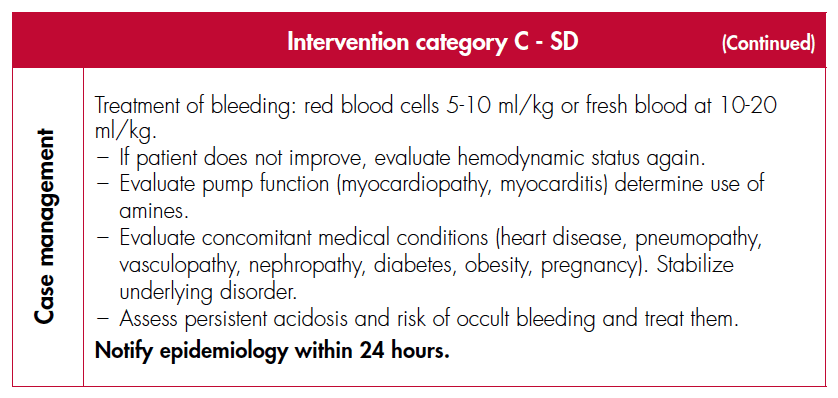

Severe Dengue is a medical emergency that requires meticulous attention to fluid resuscitation in an intensive care setting.

- 2 – 3 boluses of crystalloid at 20ml/kg is recommended prior to commencement of inotropes but this will be patient dependent (i.e. the elderly).

- A sudden drop in haemotocrit but lack of clinical improvement may indicate major bleeding and necessitate transfusion.

- If fibrinogen <100 mg/dl, transfuse 0.15 U/kg of cryoprecipitate.

- If fibrinogen >100 mg/dl and PT and aPTT are more than 1.5x the standard reference values consider fresh frozen plasma 10 ml/kg.

- Consider platelets for uncontrolled bleeding or emergent operations (platelets should be >50,000 mm3 for most operations or >100,000 for eye and neurosurgery). Patients can drop their platelet count to below 10,000 mm3, if stable only require strict bed rest.

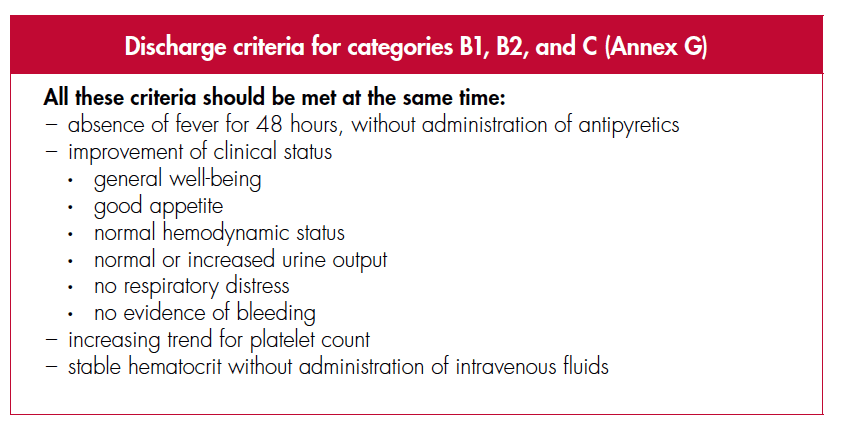

Dengue Discharge Criteria:

Q8. How do you prevent Dengue Fever?

Answer and interpretation

There is no commercially available vaccine at this stage.

Prevention consists of avoiding mosquito bites by using repellent, covering up, using indoor insect sprays and by not travelling to tropical/sub-tropical parts of the world e.g. Bali!

Case Resolution

Case Outcome

You strongly suspect Dengue Fever and a dengue antigen test confirms this the following day. Your patient improves with paracetamol and fluids and his platelet count is low-normal. You advise him to follow up with his GP for daily FBE/haematocrit and to return if his platelets are dropping or haematocrit is rising. You send him home to his Mum with paracetamol.

Further Reading

- CDC learning module on Dengue

- WHO treatment guidelines – including advice about patients with co-morbidities and pregnant patient.

References

- Beeching N, Gill G. Lecture Notes – Tropical Medicine. 7e Wiley Blackwell .

- Eddleston, Davidson, Brent, Wilkinson. Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine. Oxford Medical Handbooks. 4e

- Farrar J et al. Manson’s Tropical Diseases 23e Elsevier.

- Magill AJ, Ryan ET, Solomon T, Hill DR. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease. 9e. Elsevier.

- Grouzard V, Rigal J, Sutton M. Clinical guidelines – Diagnosis and treatment manual. Médecins Sans Frontières. 2016.

- Uptodate – Dengue fever

CLINICAL CASES

Tropical Travel Trouble

Peer Reviewers

• Dr Jennifer Ho: ID physician QLD, Australia

• Dr Mark Little: ED physician QLD, Australia

MBChB, MEmergHlth, FACEM. Kiwi emergency physician working in tropical Far North Queensland. Work interests include little people and making things happen faster and better. Outside work I'm a lifetime wonderer, devoted festival attendee, recurrent toddler wrangler and occasional body builder