James Marion Sims

James Marion Sims (1813-1883) was an American surgeon.

Often referred to as the “Father of Gynecology,” Sims is best known for pioneering surgical techniques for the repair of vesicovaginal fistulas. His work culminated in the design of the Sims speculum, which enhanced visualization of the vaginal canal, the Sims position and the Sims sigmoid catheter.

Between 1845 and 1849, Sims conducted a prolonged series of operations in Montgomery, Alabama, experimenting on enslaved Black women suffering from fistulas. Through dozens of procedures, often repeated on the same individual, he refined the surgical approach and achieved his first success in 1849.

In 1855, Sims established the Woman’s Hospital of the State of New York, the first dedicated institution for women’s health in the United States. Later he would also be appointed President of the American Medical Association (1876) and President of the American Gynaecological Society (1880).

Biographical Timeline

- Born January 25, 1813 in Lancaster County, South Carolina

- 1835 – Graduated from Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia

- 1835 – Began practicing in South Carolina but relocated after the deaths of two infant patients

- 1835-1849 Practiced throughout Alabama, primarily treating enslaved patients on plantations, and later increasingly treating the rich

- 1845 – Developed the Sims speculum and began experimental surgery for vesicovaginal fistulas using enslaved women in a small hospital built on his property

- 1849 – Achieved his first successful vesicovaginal fistula repair

- 1855 – Founded “The Woman’s Hospital of the State of New York”

- 1861-1868 Practiced in Europe during the American Civil War; reportedly treated Empress Eugénie in Paris

- 1874 – Removed as a surgeon from the Woman’s Hospital after criticising a ban on cancer patients and limitations on numbers of surgical observers in theatres

- 1876 – Elected President of the American Medical Association

- 1880 – Elected President of the American Gynaecological Society

- 1881 – Called to consult on President Garfield’s autopsy

- Died on November 13, 1883 of a heart attack in New York City

While Sims was lauded during his lifetime for his surgical ingenuity, his legacy has become increasingly contentious due to the non-consensual medical experimentation he conducted on enslaved Black women in the antebellum South. These procedures were performed without anesthesia, at a time when ether and chloroform were already available, and were often repeated multiple times on the same subjects. Sims’ notes identify several of these women by first name only (Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy). Their experiences are now central to critiques of medical ethics and systemic racism.

Further controversy surrounds his removal from the Woman’s Hospital in 1874. Disputes arose between Sims and the board of governors regarding his defiance of institutional policies, specifically his refusal to limit the number of surgical observers during operations and his objection to a ban on treating cancer patients. Sims viewed these restrictions as an affront to his professional autonomy, ultimately resigning in protest after being pressured to comply.

Though commemorated by statues and professional accolades throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, his memorials have been increasingly challenged or removed in recent years, reflecting broader societal reassessment of historical figures linked to racial injustice in medicine.

Medical Eponyms

Sims Speculum

The Sims speculum is a double-bladed vaginal retractor used for examination and surgery. Sims developed the idea in 1845 while practicing in Montgomery, Alabama. Treating a woman who had fallen from a horse and painfully retroverted her uterus, he placed her in an all-fours position and performed a vaginal examination with his finger. This distended her vagina with air and successfully anteverted her uterus. Inspired by this success, he applied the same approach to examine enslaved women with vesicovaginal fistulas whom he had previously seen and thought to be incurable.

He placed these women in the same all-fours position and using a bent pewter spoon he bought from a local store, Sims visualised the fistulas more clearly than ever and became convinced they could be cured.

Introducing the bent handle of the spoon I saw everything, as no man had ever seen before. The fistula was as plain as the nose on a man’s face

Modelled after his bent spoon, he quickly had the first versions of his speculum made and began experimenting surgically without anaesthesia on enslaved women. Three of these women are named in his autobiography as Lucy, Anarcha, and Betsey. After 30 surgeries on Anarcha alone, he eventually achieved success in repairing her fistula using silver sutures which he had also designed.

After moving to New York in 1853, Sims refined the speculum by adding a bend to the handle to improve ergonomics during long procedures.

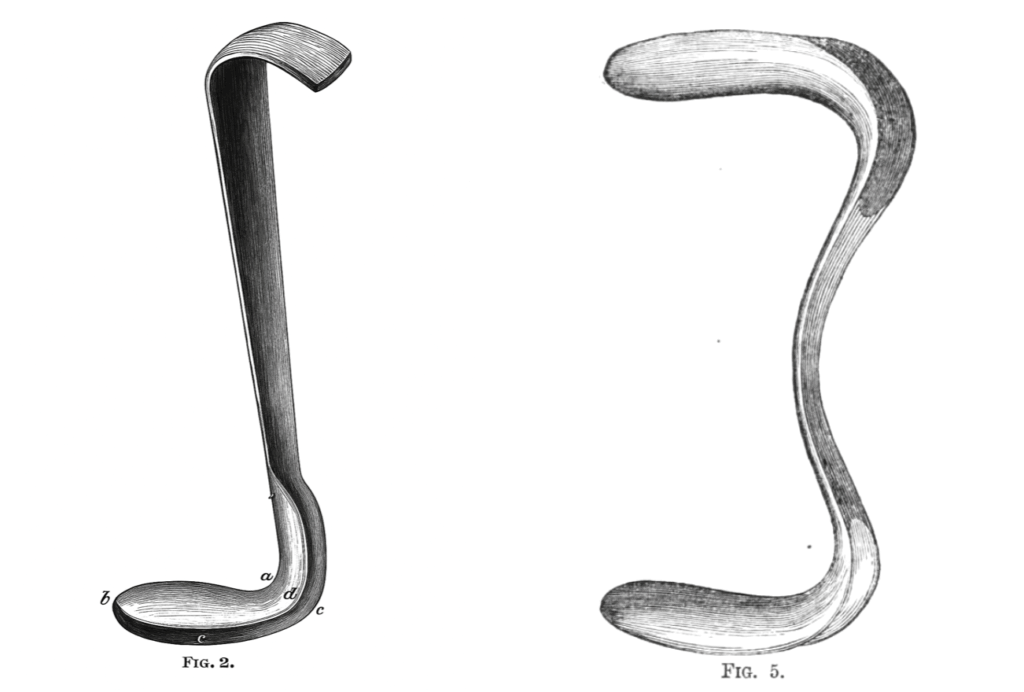

To facilitate the exhibition of the parts, the assistant on the right side of the patient introduces into the vagina the lever speculum, represented in fig. 2, and then, by lifting the perineum, stretching the sphincter, and raising up the recto-vaginal septum, it is as easy to view the whole vaginal canal as it is to examine the fauces, by turning a mouth widely open to a strong light.

The speculum is univalve or duck-billed, as some have called it. For the sake of convenience, two specula of unequal sizes are attached to the same handle, one at each extremity. This handle may be slightly bent, as seen in fig. 5, or it may be perfectly straight, as I formerly used it (fig. 2). The only object in the slight curvature is to facilitate its leverage in prolonged operations.

While the Sims speculum is often credited as the first of its kind, the first vaginal specula predate it by centuries. In his publications Sims himself acknowledges other devices and evidence exists that speculum were in use as far back as ancient Rome, with one such device found in the ruins of Pompeii and now displayed at the Museo Nazionale in Naples.

Sims Position

The Sims, or left lateral decubitus position, involves lying on the left side with the right hip and knee flexed, and the left hip and knee straight or slightly flexed. It can be used for rectal and vaginal examinations.

Sims first describes using the position after 1853 when practicing in New York, not during his surgeries on enslaved women in Alabama, as is often claimed. He introduced it as a more practical alternative to the uncomfortable all-fours position he had previously used for fistula repairs and vaginal surgery.

Although side-lying positions may have appeared in earlier medical texts, Sims is generally regarded as the first person to clearly describe and standardise the left lateral position for his uses.

Silver Sutures in Surgery 1858

In this position the thighs are to be flexed at about right angles with the pelvis, the right a little more than the left. The left arm is thrown behind, and the chest rotated forwards, bringing the sternum quite closely in contact with the table, while the spine is fully extended, with the head resting on the parietal bone.

Sims Sigmoid Catheter

Less discussed than his speculum or surgical position, Sims is also credited with the design of a sigmoid-shaped catheter which was placed through the urethra to drain urine after fistula repairs. This invention was conceived after one of his first experimental subjects Lucy nearly died of post-operative sepsis when Sims left a cloth in place as a makeshift catheter, before refining his techniques.

Typically made of tin or glass, the catheter’s curve was tailored to the patient’s anatomy to maintain continuous bladder drainage post-surgery.

Controversies

Experimentation Without Anaesthesia

Sims’ legacy is most damaged by his experimental surgeries on enslaved Black women in 1840s Alabama. These procedures, including over 30 on Anarcha alone, were performed without anaesthesia, which was not yet widely used or understood. While Sims claims that these women were consenting participants, he also describes acquiring them from their enslavers as property explicitly for experimentation.

If you will give me Anarcha and Betsey for experiment, I agree to perforin no experiment or operation on either of them to endanger their lives, and will not charge a cent for keeping them, but you must pay their taxes and clothe them. I will keep them at my own expense.

Later in his career Sims took an interest in anaesthesia and even published papers on the utility of nitrous oxide and chloroform as they became increasingly utilised. While Sims doses describe some use of opium in his publications, it is unclear if he administered it in his original experiments.

Amid growing criticism, Sims’ New York statue was taken down in 2018. Built in 1894, it was the first public statue in the United States memorialising a medical professional. In 2021 a statue named “Mothers of Gynaecology” was erected in Montgomery Alabama, recognising the women he experimented on for their contribution to gynaecology.

Confederacy

It has been speculated that during his time in Europe from 1863, Sims acted as a confederate envoy, seeking support for the South during the American Civil War. While evidence is limited, Sims openly declared his sympathies for the Confederacy in his autobiography.

His political stance is known to have sometimes caused him difficulty in Europe. When nominated for the Order of Leopold by the King of Belgium’s surgeon, the U.S. minister in Brussels objected, declaring Sims a rebel and an enemy of his country.

Additional Contributions to Women’s Health

Sims has been credited with other pioneering achievements in women’s health including the founding of “The Woman’s Hospital of the State of New York” in 1855 – considered the first in the U.S. dedicated to treating women. His motives were complex, and in his autobiography, he admits the hospital was born out of professional rejection.

Later in his career Sims publicly opposed the hospital board’s refusal to admit gynaecological cancer patients due to their concerns over odour and stigma. Subsequently, he was dismissed for insubordination. His 1876 election as AMA president was credited by his contemporaries as vindication for this action.

Publications of Note

- Sims JM. An Essay on the Pathology and Treatment of Trismus Nascentium, or Lockjaw of Infants. Philadelphia: Lea & Blanchard; 1846. Reprinted from American Journal of the Medical Sciences.

- Sims JM. Osteo‑Sarcoma of the Lower Jaw. Removal of the Body of the Bone without External Mutilation. American Journal of the Medical Sciences; 1847.

- Sims JM. On the Treatment of Vesicovaginal Fistula. American Journal of the Medical Sciences; 1852.

- Sims JM. A Review of Silver Sutures in Surgery: Anniversary Discourse before the New York Academy of Medicine. Philadelphia; 1858.

- Sims JM. Clinical Notes on Uterine Surgery, with Special Reference to the Management of the Sterile Condition. New York: Wood & Co.; 1866.

- Sims JM. On the Nitrous Oxide Gas as an Anaesthetic; with a Note by J. Thierry‑Mieg. British Medical Journal; 1868.

- Sims JM. Illustrations of the Value of the Microscope in the Treatment of the Sterile Condition. British Medical Journal; 1868

- Sims JM. On Nélaton’s Method of Resuscitation from Chloroform Narcosis. British Medical Journal; 1874.

- Hammond WA, Ashhurst J Jr, Sims JM, Hodgen JT. The Surgical Treatment of President Garfield. North American Review; 1881.

- Sims JM. The Story of My Life. New York: Appleton & Company; 1884.

References

Biography

- Baldwin WO. Tribute to the Late James Marion Sims. Montgomery: W.D. Brown & Co.; 1884.

- Wylie WG. Memorial Sketch of the Life of J. Marion Sims, M.D. New York: Appleton & Company; 1884.

- American Medical Association. Full List of Annual Meetings and Presidents. Internet Archive. Accessed July 2025.

- The Surgical Treatment of President Garfield. British Medical Journal; 1881;2(1094):989–991.

- Encyclopedia of Alabama. Photograph of J. Marion Sims. Accessed July 2025.

Eponymous terms and Controversies

- Sims JM. Clinical Notes on Uterine Surgery: With Special Reference to the Management of the Sterile Condition. Medicine in the Americas [Preprint]; 1866.

- Dudley EC. The Principles and Practice of Gynecology: For Students and Practitioners. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co.; 1904; p. 594.

- The statue of Dr. J. Marion Sims in Bryant Park. JAMA. 1894;23(18):689–690.

- Martin H, Ehrlich H, Butler F. J. Marion Sims—Pioneer Cancer Protagonist. Cancer; 1950;3(2):189–204.

- Wright HG. On the Early History of Uterine Pathology, and Use of the Speculum Among the Ancients. [Preprint]; 1865.

- Wall LL. The Sims Position and the Sims Vaginal Speculum, Re‑examined. International Urogynecology Journal; 2021;32(10):2595–2601.

- Costa CM. James Marion Sims: Some Speculations and a New Position. Medical Journal of Australia; 2003;178(12):660–663.

- Michelle Browder. Anarcha Lucy Betsey. AnarchaLucyBetsey.org; 2025. Accessed July 2025

- H.C. J. Marion Sims and the Civil War — A Rollicking Tale of Deceit and Spycraft. Montgomery Advertiser; 2018.

- Science Museum Group. Copy of Vaginal Speculum, Europe, 1901–1939. Accessed July 2025.

Eponym

the person behind the name

Junior doctor at Royal Perth Hospital. Interested in physiology, procedures, medical history and fiction. Always careful to check my blind spot when merging into the fast lane.