RUQ Pain and Jaundice

aka Tropical Travel Trouble 005

A 35 year old male presents to your emergency room for right upper quadrant pain that has gotten worse over the last 2-3 days. He also describes associated nausea, vomiting, and fevers. He denies other abdominal pain, or change in his bowel or bladder habits. His wife notes that he has started to “look more yellow” recently. The patient denies alcohol, tobacco, recreational substances, or sexual exposures.

He recently returned from a backpacking trip through Guatemala and Honduras around 6 weeks ago. His wife is quite concerned because she read online about “a parasite that dissolves your colon and liver!”

Q1. Is the patient’s wife right?

Answer and interpretation

Sort of!

Entamoeba histolytica is a protozoan parasite that can invade tissue, phagocytes cells, and cause cell lysis. It can affect most tissues in your body, but usually causes disease in the intestines and liver. Its name – histolytica—refers to disintegration and dissolution of organic tissues.

Entamoeba histolytica infections occur worldwide; an estimated 50 million people are infected, and 70,000 deaths occur per year as a result of the invasive disease (Amoebic dysentery).

Because of the high proportion of asymptomatic carriers, in some communities infection rates can be over 90%

E. histolytica infection coincides with poor sanitation, poor hygiene, overcrowding, and poverty. It is also seen in immigrants, displaced people, and travelers visiting low and middle-income countries (although it is an uncommon cause of travellers’ diarrhoea, 0.3% in one perspective study of German’s in the tropics).

Q2. How does infection occur?

Answer and interpretation

Fecal-oral fashion by ingesting E. hystolytica cysts, cysts are the infective form and can survive in the environment for weeks to months.

- The ingestion of one cyst is enough to cause disease.

- The cysts are resistant to stomach acid and pass into the small intestine.

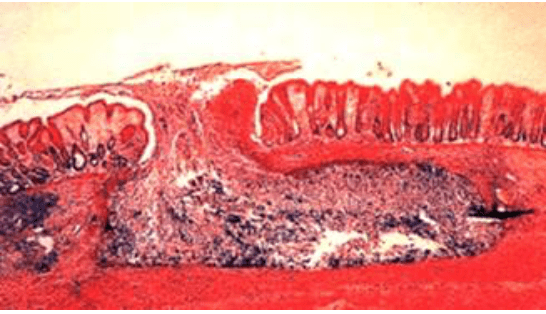

- 4 active trophozoites emerge from one cyst (each cyst has 4 nuclei), mature and travel toward the colon. The trophozoites cause the invasive disease ultimately resulting in body diarrhoea (dysentery). These trophozoites invade the mucosa by killing epithelial cells and inflammatory cells, secrete proteinases, and possibly disrupt tight junctions resulting in a characteristic flask-spaced ulcer

Q3. How does E. hystolitica infection progress?

Answer and interpretation

Around 90% of people exposed to Entamoeba histolytica will remain asymptomatic and most will eventually clear the infection without developing any clinical disease.

In 10% of exposed individuals, pathogenic amoebae invade the mucosa of the colon and cause amoebic dysentery or extra intestinal complications.

The incubation period is usually 1–4 weeks. However, in some instances clinical disease can be delayed for years. Progression of illness may be triggered by another gastrointestinal infection, systemic illness, or immunosuppression.

In intestinal amoebiasis, typically there is a subacute onset over 1-3 weeks with symptoms ranging from mild diarrhoea to severe dysentery:

- Abdominal pain 12-80%

- Diarrhoea 94-100%

- Bloody stools 94-100%

- Weight loss

- Fevers 38%

Q4. What are the two general forms of E. hystolitica amoebiasis disease, and what are the complications?

Answer and interpretation

Intestinal and Extra-intestinal.

Intestinal:

- Patients with mild disease are quite well; they relate a history of insidious onset of abdominal discomfort with nonspecific loose stools rarely containing mucous or blood.

- In more severe disease, patients can produce 5–15 bloody stools a day, complain of abdominal pain and tenesmus. On exam, they reveal abdominal tenderness, but often remain non-toxic and afebrile.

- Fevers and constitutional symptoms occur in a minority of cases. Immunosuppressed patients are more likely to present with fulminant colitis. As the colonic ulcerations coalesce, areas of necrosis can develop and cause perforation and peritonitis.

- Complications from intestinal amoebiasis include:

- Hemorrhage

- Bowel perforation (0.5%)

- Peritonitis (amoebic and bacterial)

- Toxic megacolon

- Amoebic appendicitis

- Amoeboma, and strictures. Amoebomas (also called amoebic granulomas) are inflammatory masses that occur after chronic, repeated ulcerations by E. Hystolitica. They occur most commonly in the cecum, can mimic carcinoma, and can present as bowel obstructions or intussusception. This same process of chronic fibrosis can lead to the formation of colonic strictures.

Extra-intestinal Amoebiasis:

E. histolytica has the capacity to travel to and destroy almost all tissues of the human body. Hematogenous or direct spread can lead to infections of the liver, lungs, heart, brain, kidneys, skin, cartilage, and bone.

Amoebic Liver Abscesses

- Amoebic Liver Abscesses are the most common form of extra-intestinal amoebiasis; they occur after invasive trophozoites travel to the liver via the portal circulation.

- Signs and symptoms of amoebic liver abscess include: florid progression of fever with rigors, RUQ dull/achy pain that is worse with deep inspiration or lying on the right side, referred pain to right shoulder blade (secondary to diaphragm irritation), pleuritic chest pain +/- nonproductive cough, hepatomegaly with point tenderness under or between the ribs (Durban’s sign). If the abscess develops at the dome of the liver, tender hepatomegaly may not be appreciated, a hiccup or respiratory findings will likely be more prominent (including development of a pleural effusion).

- Amoebic liver abscess can occur even in the absence of current gastrointestinal symptoms. Concomitant dysentery or diarrhoea occur in only 10–35% patients with a liver abscess, less than 50% have a history of dysentery within the prior month, and many have no history of dysentery.

- The right lobe of the liver is four times more likely to be affected than the left. Men are 10x more likely to get an abscess and it often occurs in the 4th or 5th decade of life.

- Lab investigations reveal bilirubin elevation in 10-25% of patients, leukocytosis in 63-94% of patients, elevated transaminases in 26-50% of patients, elevated alkaline phosphatase in 38-84% of patients, and elevated ESR in 81% of patients.

- The appearance of abscess fluid is classically described as “anchovy paste” or “chocolate syrup.” The abscess fluid is mostly composed of liquified hepatocytes, as the amoebae tend to localise to the periphery. It will contain cellular debris but few cells and will often be bacteriologically sterile, although secondary bacterial infection can occur.

Other

- Pleuropulmonary amoebiasis is the most common complication of amoebic liver abscess, and occurs when a superior right liver lobe abscess erodes through the diaphragm. This can result in pneumonia, pneumonitis, lung abscess, and bronchohepatic fistula formation. Patients often have acute development of right chest pain, cough, and expectoration of large volumes of dark brown fluid.

- Pericardial Amoebiasis occurs in less than 1% of amoebic liver abscesses, but is more common if the left lobe is affected. There is often a precursor stage where a sterile pericardial effusion forms (a friction rub might be appreciated), but invasion of the abscess into the pericardium commonly results in tamponade and death in ~40% of patients. Subsequent loculations are common, necessitating open drainage of the pericardial sac.

- Cerebral amoebiasis has been described in less than 0.1% of patients in large clinical series, but has been documented in up to 2.5% of patients who have amoebiasis at autopsy. Although the symptoms of cerebral involvement depend on the lesion, reports often show abrupt onset of symptoms and death within 12–72 hours if treatment is delayed or indequate. Therefore, high clinical suspicion for cerebral involvement should be demonstrated when patients have a change in mental status or focal neurological signs; an emergent head CT should be performed.

- Cutaneous Amoebiasis can occur secondary to abscess perforation or intestinal fistulisation into the skin. Direct inoculation of this skin can also lead to cutaneous ulcers. Lesions are well-demarcated, round, with elevated borders and punched-out, necrotic centers, and often produce copious exudate.

- Perianal fistulas, rectovaginal fistulas, and vulvar and penile skin ulcerations can occur as a result of intestinal disease or secondary to sexual transmission.

- Surgical wounds can become infected if invaded by a nearby or internal amoebic lesion. Trophozoites can be seen under microscopy in fresh ulcer discharge or scrapings of the ulcer edge.

Q5. What is the differential diagnosis for Amoebic liver abscess?

Answer and interpretation

- Pyogenic abscess.

- Primary hepatocellular carcinoma or metastasis to liver.

- Hydatid cyst.

- Tuberculosis.

- Syphilitic gumma.

Q6. What diagnostic studies can be utilised?

Answer and interpretation

Stool Microscopy:

- The gold standard diagnosis of amoebic dysentery is made by finding motile hematophagous trophozoites (trophozoites which have phagocytosed red blood cells) in a fresh stool sample (i.e. look within 15 minutes).

- This remains the main-stay of diagnosis in resource-limited settings. Sensitivity can increase to 85% if 3 samples are sent.

- The cysts of E. histolytica are indistinguishable from E. dispar (a non-pathogenic amoeba), and therefore, visualisation of cysts can be suggestive of disease but do not confirm amoebic dysentery.

- As stated above, most cases of extra-intestinal abscess exist without coexisting intestinal infection; stool studies are only 40% sensitive for detection of E. histolytica in patients with amoebic liver abscess.

Antigen tests and serology:

- Stool antigen tests are generally available in more affluent settings and significantly improve upon the specificity and sensitivity of wet prep stool analysis. The development of enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) allows for a simple rapid diagnostic tests

- Stated sensitivities and specificities of these kits all exceed 90% compared to culture. Importantly, these tests can distinguish between E. histolytica (pathogenic ameba) and E. dispar (non-pathogenic).

- Serological tests are more useful in non-endemic areas. Specific antibodies are present in up to 95% of patients with invasive disease, but in endemic areas many people will show positive serology because of recent infection or asymptomatic infection.

- It takes approximately 5-7 days for patients to develop antibodies which may persist for years. Therefore in an endemic area, a negative test is useful to exclude disease.

- Indirect haemagglutination (IHA) by ELISA tests are usually negative after 6-12 months, and could be of better use in endemic areas.

- PCR techniques for detecting parasitic DNA or RNA are 100% specific and more sensitive than microscopy for E.histolytica but will be laboratory dependent.

Non-specific blood tests:

- In mild cases of amoebic colitis, laboratory tests are often normal.

- Leukocytosis is often present in severe disease and in patients with amoebic liver abscesses.

- Eosinophilia is not associated with extra-intestinal amoebiasis.

- Anaemia is common, secondary to chronic liver abscess or acute hemorrhage from colonic ulcers.

- The level of alkaline phosphatase is raised in more than 75% of patients.

- Transaminitis is present in 50% of cases, especially in patients with acute disease or complications.

- Transaminitis usually resolves quickly with therapy, but alkaline phosphatase may remain raised for several months.

Endoscopy:

- Colonoscopy is particularly useful in patients with suspected amoebiasis, but who have negative or inconclusive stool microscopy or antigen tests. Ulcerations are appreciated in acute and chronic cases.

- Scrapings or aspirates from the ulcer contain erythrophagocytic trophozoites of E. histolytica and should be positive on antigen testing.

Imaging:

- AXR: In an acutely toxic patient, who shows signs of peritonitis, a plain abdominal radiograph should be obtained to check for free air or megacolon.

- CXR: In patients with liver abscess, a chest x-ray might reveal a right hemidiaphragm elevation or costophrenic blunting from a pleural effusion.

- Imaging of the liver by ultrasonography, CT, or MRI will reveal amoebic liver abscess.

- Utrasound is a useful study to obtain in suspected hepatic involvement; it typically reveals a round hypoechoic region, contiguous with the liver capsule and without pronounced wall echo.

- CT with IV contrast shows the non-enhancing abscess center, surrounded by an irregular rim of in inflammation/enhancement. CT does not definitively discern between amoebic and pyogenic liver abscess.

Q7. How can you tell the difference between an Amoebic liver abscess and a pyogenic liver abscess?

Answer and interpretation

- Pyogenic and amoebic liver abscesses cannot be distinguished clinically, but there are differences in disease pattern that can assist in the right clinical context.

- In low and middle-income countries, amoebic liver abscesses are more common.

- Pyogenic abscesses tend to be multiple as opposed to the large, single amoebic abscess in the right lobe.

- Pyogenic liver abscesses have positive blood cultures in 50% of patients and patients tend to be older than 50 years.

- Patients with amoebic abscesses are more likely to present with jaundice.

- Empiric antibiotics can be utilised, however, if the patient progresses and the diagnosis remains elusive despite blood cultures, stool studies, serology, and imaging, most patients have an aspiration performed. As discussed above, amoebic abscess aspirate is described as “anchovy paste” or “chocolate syrup,” and gram stain is negative (unless secondary bacterial infection has occurred).

Q8. What is the treatment of Amoebic dysentery and Amoebic Liver abscess?

Answer and interpretation

Two classes of drugs are used to treat amoebic infections:

- Tissue amoebicides — such as metronidazole, tinidazole, nitazoxanide, chloroquine — that are effective against invasive amoebiasis.

- Luminal amoebicides — diloxanide furoate, paromycin, iodoquinol — that act on amoeba in the intestinal lumen.

For amoebic dysentery, a treatment course of a tissue amoebecide should be given, followed by a course of a luminal amoebicide to rid the intestine of persistent parasites.

- Metronidazole 500 – 750mg PO TDS for 7 to 10 days (35 – 50mg/kg in children).

- Or tindazole 2g for 5 days in adults.

And

- Paromomycin 25-30 mg/kg PO in 3 divided doses for 7 days.

- Or diiodohydroxyguin 650mg PO TDS for 20 days in adults (30-40 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses in children).

- Or diloxanide furoate 500mg PO TDS for 10 days in adults (20mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses in children).

For amoebic liver abscess: metronidazole or tinidazole followed by diloxanide furoate is the treatment of choice as per the above regimens.

Aspiration is indicated:

- To rule out pyogenic abscess (especially if multiple lesions), as adjunct to medical therapy (no response in 72 hours).

- If rupture is imminent.

- If the abscess is >/= 10cm, or if the abscess is in left lobe (increased potential to rupture with critical complications).

- Surgery should be performed for abscess rupture, bacterial superinfection, or if abscess needs aspiration but percutaneous access limited by anatomy.

- Perforation, toxic megacolon or abscesses that fail medical treatment, all need surgical intervention +/- broad spectrum antibiotics.

Case Resolution

Case Outcome

- Bedside ultrasound revealed a single 7×4 cm fluid collection in the right lobe of the liver and no lung findings. CXR was negative for acute pathology. The patient was started on IV piperacillin/tazobactam and metronidazole. Stool wet prep was negative for amoeba, stool serology was positive for E. Hystolitica.

- After 3 days, that patient continued to have pain, fever, and no change in his leukocytosis.

- Repeat imaging of his liver revealed no change in size. Percutaneous aspiration of the liver lesions was performed and revealed chocolate-milk appearing fluid. Gram smear was negative for bacteria and piperacillin/tazobactam was discontinued.

- The patient rapidly improved over the next 2 days. He continued metronidazole for 10 days and then was given a 10 day course of oral diloxanide furoate.

References

- Beeching N, Gill G. Lecture Notes – Tropical Medicine. 7e Wiley Blackwell .

- Eddleston, Davidson, Brent, Wilkinson. Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine. Oxford Medical Handbooks. 4e

- Farrar J et al. Manson’s Tropical Diseases 23e Elsevier. .

- Magill AJ, Ryan ET, Solomon T, Hill DR. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease. 9e. Elsevier.

- Grouzard V, Rigal J, Sutton M. Clinical guidelines – Diagnosis and treatment manual. Médecins Sans Frontières. 2016.

- Uptodate – Intestinal and Extraintestinal Amoebiasis

Guest Post

Global Health Fellow, Department of Emergency Medicine. UT Health San Antonio, @SkarpMD

Branden Skarpiak, MD

CLINICAL CASES

Tropical Travel Trouble

Dr Neil Long BMBS FACEM FRCEM FRCPC. Emergency Physician at Kelowna hospital, British Columbia. Loves the misery of alpine climbing and working in austere environments (namely tertiary trauma centres). Supporter of FOAMed, lifelong education and trying to find that elusive peak performance.