Whipple disease

Whipple disease is a rare systemic infectious disorder caused by Tropheryma whipplei. It typically presents with chronic weight loss, malabsorption, steatorrhoea, arthralgia, lymphadenopathy and fever.

In the small intestine, infiltration of foamy macrophages containing PAS‑positive material leads to impaired lymphatic drainage, fat malabsorption and systemic manifestations. The disease historically carried nearly 100 % mortality, but with modern antibiotic regimens (initial IV therapy followed by long‑term oral treatment) the prognosis has dramatically improved.

Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and is supported by duodenal or jejunal biopsy showing PAS‑positive macrophages, PCR detection of T. whipplei, and sometimes electron microscopy displaying intracellular bacillary structures.

Given the multisystem nature, neurologic, cardiac and ocular involvement may occur, increasing complexity of treatment. Although once considered almost exclusively fatal, contemporary management emphasises prolonged therapy, relapse monitoring, and awareness that immune suppression may unmask or worsen disease.

History of Whipple disease

1895 – Sir William Henry Allchin (1846–1912) and Richard Grainger Hebb (1848-1918) reported a case of a 38-year-old man (F.J.) with chronic diarrhoea, cachexia, and ultimately death within 24 hours of hospital admission. At autopsy, the small intestine, especially the duodenum and jejunum showed:

The entire mucosa is beset with myriads of whitish flocculi, which give it a shaggy, coarsely villous appearance… Microscopical examination of the intestine confirms the view that the appearances are due to dilatation of the lymphatic vessels… Sections show large coarse villi containing varicose lacteals, which are distended with an amorphous, finely granular substance containing a few cells

Allchin, Hebb 1895

Right: A portion of the same under higher magnification, the distended lymphatic spaces stand outclearly.

Though Allchin and Hebb suspected lymphatic obstruction and their pathological findings foreshadow the mucosal and lymphatic features now recognised in Whipple disease.

1907 – George Hoyt Whipple published a hitherto undescribed disease characterized anatomically by deposits of fat and fatty acid in the intestinal and mesenteric lymphatic tissues. He detailed the fatal course a 36-year-old physician, suffering weight loss, chronic diarrhoea, weakness, and arthritis.

The lymphatic glands of the mesentery and small intestine are large, pinkish-gray, firm, and fatty. Microscopic study shows that these glands are filled with fat, both in the form of droplets and of fatty acids, and that there is a complete absence of the normal lymphoid structure

Whipple GH, 1907

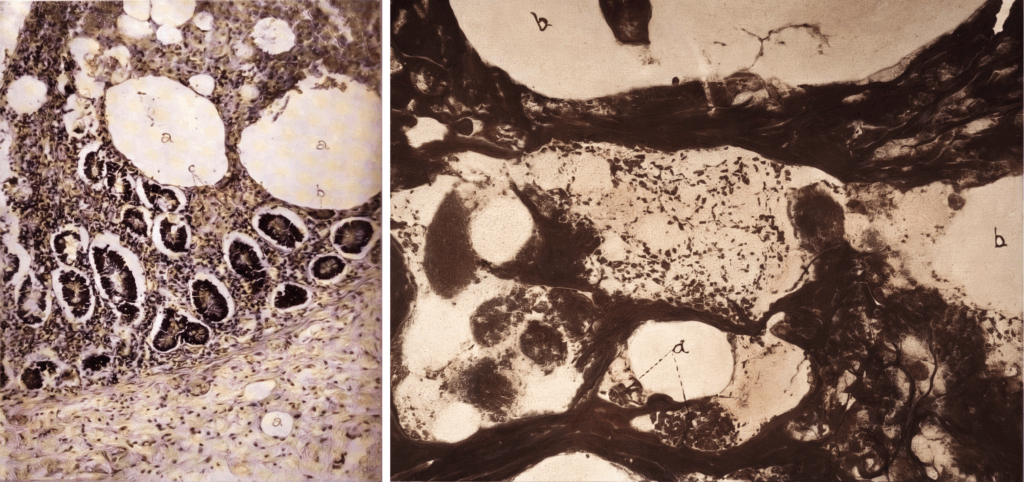

Right: Fig 9: Section of gland stained by Levaditi method. Vacuole (a) containing rod-shaped organism (?)

Whipple named the disorder “intestinal lipodystrophy” based on his belief that altered fat metabolism played a role in its pathogenesis. He also noted numerous rod-shaped organisms in a silver stained lymph node from his case, but the significance of this observation was not apparent in 1907.

1949 – Bernard Black-Schaffer (1910-2009) discovered the hallmark periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive staining in duodenal macrophages, a defining diagnostic feature. This confirmed that the foamy macrophages observed by Whipple contained glycoprotein-rich bacterial remnants, though the causative organism was still unknown.

1952 – The infectious nature of Whipple disease became apparent when antibiotics trials demonstrated that patients could be cured of this usually fatal disease. John Wylmer Paulley (1918-2007) reported a case successfully treated with antibiotics (tetracycline), strongly suggesting an infectious aetiology. He emphasised duodenal biopsy findings and linked antibiotic response to clinical remission, paving the way for non-fatal management of the disease.

1961 – Yardley and Hendrix used combined light and electron microscopy to demonstrate bacillary structures within PAS-positive macrophages. They correlated the disappearance of these organisms with clinical recovery post-antibiotic treatment, reinforcing the microbial cause.

1992 – Relman et al. used PCR-based molecular methods to identify the previously uncultured bacillus, naming it Tropheryma whippelii. This confirmed that Whipple disease was caused by a Gram-positive actinomycete, a major breakthrough in its microbial classification.

1997–2000 – Culturing and Genomic Identification. The organism was finally cultured in vitro in 2000. Complete genome sequencing revealed an intracellular pathogen with a reduced genome, consistent with its reliance on the host cell for survival.

2001 – La Scola et al renamed Tropheryma whippelii as Tropheryma whipplei

In order to avoid any confusion that could result from the introduction of a new name, especially for clinicians with patients suffering from Whipple’s disease, we propose to retain the name Tropheryma whipplei. We have corrected ‘whippelii’ to whipplei, as the name Whipple must be correctly Latinised to whippleus and thus the genitive is whipplei.

La Scola, 2001

Associated Persons

- Sir William Henry Allchin (1846–1912)

- Richard Grainger Hebb (1848-1918)

- George Hoyt Whipple (1878-1976)

- Bernard Black-Schaffer (1910-2009)

- John Wylmer Paulley (1918-2007)

Alternative names

- Whipple’s disease

- Intestinal lipodystrophy

- Whipple’s intestinal lipodystrophy

References

Original Articles

- Allchin WH, Hebb RG. Lymphangiectasis intestini. Transactions of the Pathological Society of London 1895; 46: 221-223

- Whipple GH. A hitherto undescribed disease characterized anatomically by deposits of fat and fatty acid in the intestinal and mesenteric lymphatic tissues. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1907;18:382–393.

- Black-Schaffer B. The tinctoral demonstration of a glycoprotein in Whipple’s disease. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1949 Oct;72(1):225-7.

- Paulley JW. A case of Whipple’s disease (intestinal lipodystrophy). Gastroenterology. 1952; 22(1): 128-133

- Yardley JH, Hendrix TR. Combined electron and light microscopy in Whipple’s disease. Demonstration of “bacillary bodies” in the intestine. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1961 Aug;109:80-98.

- Relman DA, Schmidt TM, MacDermott RP, Falkow S. Identification of the uncultured bacillus of Whipple’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1992 Jul 30;327(5):293-301.

Review articles

- Morgan AD. The first recorded case of Whipple’s disease? Gut. 1961 Dec;2(4):370-2.

- Haubrich WS. Whipple of Whipple’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(3):576

- Strausbaugh LJ, Maiwald M, Relman D. Whipple’s disease and Tropheryma whippelii: secrets slowly revealed. Clin Infect Dis. 2001 Feb 1;32(3):457-463

- Dutly F, Altwegg M. Whipple’s disease and “Tropheryma whippelii”. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001 Jul;14(3):561-583.

- La Scola B, Fenollar F, Fournier PE, Altwegg M, Mallet MN, Raoult D. Description of Tropheryma whipplei gen. nov., sp. nov., the Whipple’s disease bacillus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2001 Jul;51(Pt 4):1471-1479.

- Antunes C, Singhal M. Whipple Disease. 2023 Jul 4. In: StatPearls

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |