Another Ankle Sprain

aka Bone and Joint Bamboozler 009

A 23 year-old female netball player presents with pain and swelling of her right ankle after injuring it while playing netball. She states she landed heavily, inverting her right ankle, after jumping up to defend a goal shot, but was able to play on for another 2-3 minutes before the pain, and swelling became too uncomfortable.

The patient hobbles into minor injuries room, where you elevate the leg, provided ice, analgesia, and start to wonder if she meets the criteria for X-ray to rule out a fracture…

What is the typical history of an ankle sprain?

Answer and interpretation

“Sprains are due to forced inversion or eversion of the ankle, usually while the ankle is plantar-flexed.”

- Ankle sprains occur in 75% of ankle injuries making this a common presentation to emergency departments, however these injuries are commonly mismanaged.

- The prevalence of ankle fractures among emergency department patients diagnosed with ankle sprains is about 15%.

- Most sprains commonly occur between the ages of 15-35 years, and generally occurs in sports such as netball, basketball, running and the various football codes.

- 85% of ankle sprains result from inversion stress that causes lateral ligamentous injury.

- Inversion stress affects the lateral joint capsule, and the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL), with isolated injury to the ATFL occurring in 60-70% of ankle sprains.

- When greater force is applied to the ankle the calcanofibular ligament (CFL) and the posterior talofibular ligament (PTFL) are also at risk of being injured.

- Eversion injuries generally don’t result in ankle sprains as the deltoid ligament is strong, however forceful injuries may rest in malleolar fractures.

How do you determine the severity of ankle sprains?

Answer and interpretation

Ankle sprains can be catergorised into three different degrees of severity, as determined by the amount of ligament instability on stress testing. In the acute setting adequate assessment of ligament integrity may be hindered by pain and swelling.

First degree: Ligament injury with-out tear

- Minimal functional loss (patient ambulates with minimal pain

- Minimal swelling

- Mildly tender over involved ligament

- No abnormal motion or pain on stress testing

Second–degree: Incomplete tear of a ligament

- Moderate functional loss (patient has pain with weight bearing and ambulation)

- Moderate swelling, ecchymosis, and tenderness

- Pain on normal motion

- Mild instability and moderate to severe pain on stress testing

Third-degree: Complete tear of a ligament

- Significant functional loss (patient is unable to bear weight or ambulate)

- Egg-shaped swelling within 2 hours of injury

- May be painless with complete rupture

- Positive stress test

What conditions may mimic an ankle sprain?

Answer and interpretation

Table adapted from from Hanlon, D. (2010) summary of entities that can mimic ankle sprains:

How do you approach ankle sprains and assess for ligament instability?

Answer and interpretation

Begin your assessment with:

- Look: for any bruising, swelling, erythema or deformity

- Feel: all structures below the knee, focusing on the head of the fibula, the calf, the Achilles tendon, the heel, the malleoli, and the base of the fifth metatarsal.

- Move: will generally be difficult with the acute swollen ankle, however assess ability to weight bear, and ligament stability.

The following video provides a nice review on ankle assessment

Assessing the ligaments:

- Assess the lateral malleolus, if swelling increases the size of the ankle by 4cm this has a probability of ligament rupture of 70%.

- Tenderness on palpation of the CFL suggesst rupture in 72% of cases, with the same occurring over the ATFL in 52% of cases.

- Patients demonstrating all 3 of these signs have a 91% chance of severe ligament rupture.

Stress Testing the ligaments:

- Anterior draw test: is a test of ankle instability.

- Flex the patients knee, stabilise the tibia by cupping the heel, and move the ankle mortise joint in an anteroposterior direction.

- A positive test is asymmetric ankle excursion.

- Talar tilt test: indicates ankle instability.

- Inversion at the ankle causing tilting and lifting of the mortise joint.

- A positive test is asymmetric ankle excursion.

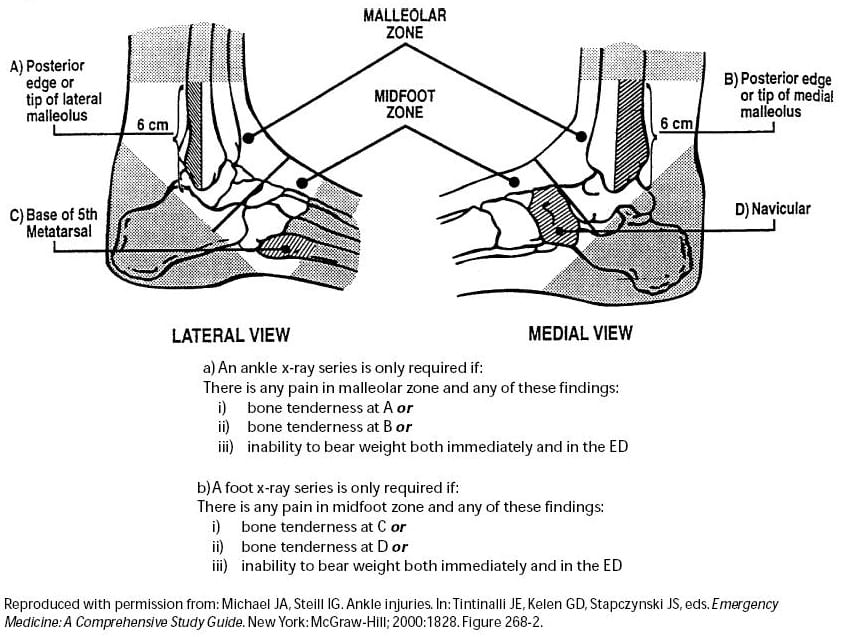

Which patients require an X-ray?

Answer and interpretation

The Ottawa ankle rules were developed to limit the amount of patients requiring X-rays, and the associated costs to the health system. The OAR were derived so that if the criteria for the rules are met, fractures can be effectively ruled out based on the clinical evaluation without the need for radiographs.

A recent systematic review by Bachmann, L. et al (2003) assessed the accuracy of the OAR in excluding fractures of the mid-foot and ankle. There was close to 100% sensitivity and a modest specificity. Used correctly the OAR should reduce unnecessary radiographs by about 30-40%.

What is the best way to manage ankle sprains in the ED?

Answer and interpretation

General Managent Principles (P.R.I.C.E.R)

- Protection: Give the patients crutches or a wheelchair during triage to protect the limb from further injury until assessment is completed

- Rest: An initial brief period of rest is advised to prevent further muscle damage, scaring and further trauma, however prolonged immobilisation is discouraged as result in new fibres to be weak and poorly organised.

- Ice: Ice is recommend in the initial stage of the injury with limited evidence to support continued use beyond this, and may even increase swelling. Apply every 2-3 hours for the first 24 hours. Ice works by causing local vasoconstriction preventing further bleeding to injury site, slows metabolism of oxygen at injury site, which then reduces cell death, which has a knock-on effect on decreasing the inflammatory process. The cold may also reduce nerve conduction at the site, providing analgesia to the patient.

- Compression: Bandages may discourage bleeding and swelling by exerting circumferential pressure on the limb, evidence shows most benefit is gain in the first 3 days after injury. Compression bandages should be avoided during periods of elevation as they may compromise circulation. Compression bandages should be applied firmly enough to assist in venous and lymphatic drainage, but not compromise arterial flow.

- Elevation: Elevating the limb above the heart may help to relieve swelling, and can be used when a compression device is not in-situ.

- Referral: Arrange for review and follow up with GP, physiotherapist or orthopaedic surgeon.

First Degree Ankle Sprain

- Encourage and implement P.R.I.C.E.R.

- Provided simple analgesia (paracetamol, NSAIDS)

- Tubi-grip or elastic support bandage for compression and ligament support

- Encourage early weight bearing, aiming for a return to full activity within a week

- Follow up with GP or physiotherapist.

Second Degree Ankle Sprain

- Encourage and implement P.R.I.C.E.R.

- Provided simple analgesia (paracetamol, NSAIDS)

- Provided ankle support which gives more stability than elastic compression bandages, for example airsplint, ankle-boot, bimalleolar orthotics. (Physiotherapist involvement is recommended)

- Patients should not weight bear for the first 48-72 hours, provide crutches to help reinforce this advice

- Follow up should be arrange with GP and physiotherapist for further monitoring and rehabilitation

Third Degree Ankle Sprain

- Encourage and implement P.R.I.C.E.R.

- Provided simple analgesia (paracetamol, NSAIDS) may require more analgesia due to severity of injury.

- Management becomes more controversial.

- A recent study found immobilisation in a plaster cast or air-splint for 10 days had a faster recovery over elastic bandage and early mobilisation. (abstract)

- These patients require close follow up with GP or orthopaedic surgeon and further management and rehabilitation by a physiotherapist.

References

- Bachamann, L. et.al. (2003). Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ. [BMJ Full text)]

- Hanlon, D. (2010). Leg, Ankle, and Foot Injuries. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. [PMID 20971396]

- Lamb, S. et.al. (2009). Mechanical support for acute, severe ankle sprain: a pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. [PMIS: 19217992]

- Sherman, S. Simon’s Emergency Orthopedics 7e

- Purcell, D. Minor Injuries A Clinical Guide 3e

- Pines, J Evidence-Based Emergency Care Diagnostic Testing and Clinical Decision Rules

CLINICAL CASES

Bone and Joint Bamboozler

Emergency nurse with ultra-keen interest in the realms of toxicology, sepsis, eLearning and the management of critical care in the Emergency Department | LinkedIn |