Approach to Snakebite

Potential or definite snakebite is a common presentation to Australian emergency departments. Fortunately it is rare to have a severe envenoming as many bites will have insufficient venom injected (dry bite). However, due to the potential lethality of snakebites they should be managed with a time-critical robust approach as detailed below regardless of clinical appearance:

Prehospital

First Aid:

- Keep the patient calm

- Avoid unproven techniques such as tourniquets or sucking the bite

- Apply a Pressure Bandage Immobilisation (PBI)

PBI Video

- Preferentially an elasticated bandage is preferred for a PBI at a pressure similar to a sprained ankle

- The use of a PBI 4 hours post bite is unlikely to be effective

- Immobilise the whole patient

- If the bite is on the torso, apply local pressure to the area and immobilise the patient

- Do not wash the wound as in a few cases a wound swab will be required for a CSL Snake Venom Detection Kit (SVDK)

- The PBI should not be removed until the patient has been fully assessed and found to show no objective evidence of envenomation or they have been envenomed and receiving antivenom (usually the PBI is removed once half of the antivenom has been infused)

Transport

The patient requires a hospital that has the following:

- A doctor that can manage snakebites and potential complications (e.g. anaphylaxis)

- 24 hours laboratory capability

- Adequate stocks of antivenom or capability of this being transported to the hospital in a timely fashion

If the above is not met, initial management may occur at the first site and then retrieval services will transfer out. If envenomation is clinically evident then antivenom maybe brought out by the retrieval services and started en-route to the next hospital.

Hospital

Resuscitation

- Most patients with a history of snakebite do not require immediate resuscitation but should be initially assessed in a an area capable of cardiorespiratory monitoring

- Establish IV access

- Early Life threats include:

- Cardiac Arrest (most commonly seen with brown snake envenomation, although rare, 1 ampule of antivenom can be given undiluted as an IV push and resuscitation proceeds along conventional lines)

- Sudden Collapse (hypotension)

- Respiratory Failure secondary to paralysis

- Seizures

- Uncontrolled haemorrhage secondary to severe venom-induced consumptive coagulopathy (VICC)

Envenomed or not?

The aim over the next 12 hours (post bite) is to determine if the patient has been envenomed and if so, which snake is responsible. This is based on the history, examination and investigations (never use bedside point-of-care INR and D-dimer as they are inaccurate).

How often do I examine or do bloods?

1. Abnormal physical exam or initial laboratory results consistent with envenomation: Antivenom therapy is required. See below for determining the type of monovalent antivenom required.

2. Patient is clinically well and has normal initial laboratory results: The PBI is removed. If there is immediate deterioration then the PBI is reapplied, laboratory studies are repeated and antivenom is administered.

3. No deterioration post PBI removal:

- Physical examination and laboratory studies 1 hour post PBI removal, then ….

- Physical examination and laboratory studies 6 hours post bite, then …

- Physical examination and laboratory studies 12 hours post bite (also at least 6 hours post removal of PBI)

If at any of these points there are physical or laboratory evidence of envenomation then antivenom is administered. It is often wise to educate the patient about the subtle exam findings such as double vision so they can alert nursing staff if this occurs.

4. No evidence of envenoming 12 hours post bite: The patient can be discharged if it is not during the night (subtle neurotoxicity may not be detected).

Determining the type of monovalent antivenom required:

Ideally monovalent antivenom should be used, it is cheaper and safer to use. The polyvalent antivenom contains one ampuole of each monovalent therefore the high protein load has a higher risk of anaphylaxis. Polyvalent is used when it is not possible to narrow the choice of antivenoms down to two monovalents.

Classically we chose our monovalent based on the geographical history, physical findings and the laboratory results, Below are the tables used to determine which antivenom to use. It is best practise to discuss your choice of antivenom with a toxicologist as local knowledge can change the choice of antivenom (snakes don’t read maps).

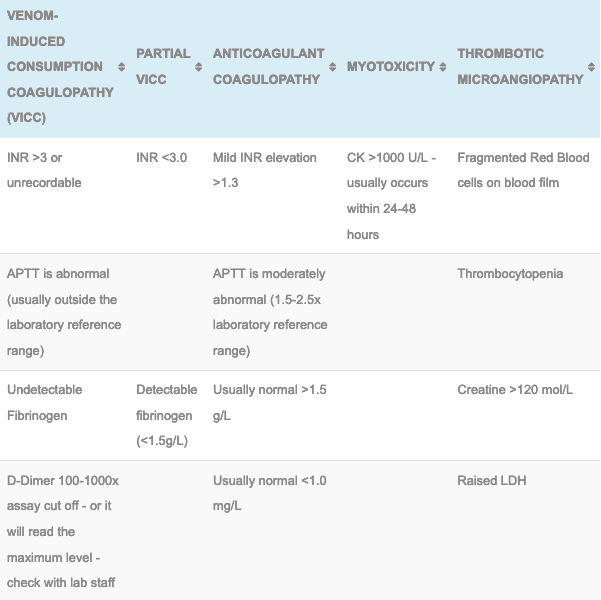

My easy (easier) method/tips for remembering envenomation effects:

- Any snake that causes a VICC can cause a Thrombotic microangiopathy

- Brown, Tiger and Taipan cause VICC (or a partial VICC)

- The Taipan is like the Tiger but on steroids!! It will also cause neurotoxicity as well as VICC

- Black = mild anticoagulant coagulopathy, like you’ve been injected with heparin – mildly raised APTT

- Death and rarely Sea Snakes cause neurotoxicity

Putting it all together with the following examples:

- Snakebite in Tasmania with VICC = Tiger (only venomous snake in Tasmania and the Tiger snake causes a VICC)

- Snakebite in Melbourne with VICC = Tiger and Brown (only two to cause a VICC in this area), if the patient had a anticoagulant coagulopathy then the Red-Bellied Black snake would be responsible and Black or tiger antivenom could be used

- Snakebite in the North West at night, no laboratory abnormalities but the patient has decending paralysis = Death Adder, only one in that area to cause paralysis without a laboratory derangement.

Administering Antivenom:

- One vial of antivenom is now recommended to treat children and adults for all snake types. This data is based on on the Australian Snakebite Project (ASP) studies. Over the past 15 studies there has been no evidence that more antivenom is required but beware that in exceptional circumstances, some toxicologists have given repeated doses for patient who are severely unwell (always consult if your are considering another vial due to the risks of complications).

- Please see our antivenom page for more details on administration and complications. The clinician should be prepared for the possibility of anaphylaxis.

- Following antivenom administration the bloods are repeated after 6 hours and 12 hours. Then every 12 hours until they have normalised. Even with antivenom it may take 24-36 hours for the coagulation studies to return to normal (Median time for INR <2.0 is 15 hours).

Adjuvant therapy

- Update tetanus prophylaxis

- If the patient has a potentially life-threatening bleed then the administration of FFP is reasonable. FFP however, has not been proven to have clinical benefit in other patient groups.

- Neuromuscular paralysis and myotoxicity with acute renal failure will need to be managed with supportive care in a high-dependency area. Some patients may require ventilatory support for days or weeks and those with severe myotoxicity may need dialysis.

- Patients with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) may also need dialysis and close electrolyte monitoring. As yet there has been no evidence to support the use of plasmapheresis in TMA but consultation with a haematologist and renal physician is recommended due to the limited evidence in this area.

The CSL Snake Venom Detection Kit (SVDK) use and warning:

- The SVDK is not used to diagnose envenomation but only to support the choice of monovalent antivenom once the choice to administer antivenom had been made.

- If you have a choice of two snakes and the SVDK is indeterminate it is better to give 2 monovalent antivenins than the polyvalent.

- Ideally the SVDK should be performed by a bite site swab but urine can be used as second line (never serum or blood)

- False positives and false negative occur – treat the patient, not the SVDK

- 1 in 10 tiger snake envenomations have shown positive for brown snake with the SVDK

- Another study showed an incorrect diagnosis in 14% of snake handlers when the exact snake was known

- Fasle negatives can be as high as 25%

- Many toxicologists will use the tables shown above to determine the best monovalent to use.

References and Additional Resources:

Additional Resources:

- Chris Nickson’s talk on assessing the snakebite

- GK Isbister – Does antivenom work? SMACC Podcast

- Antivenom

- Tox Conundrum 005 – Snakebite vs Stickbite

- Tox Conundrum 026 – Snakebite Envenoming Challenge

References:

- Isbister GK, Brown SGA, McCoubrie DL, Green SL, Buckley NA. Snakebite in Australia: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment. Medical Journal of Australia 2013; 199:793-798

- White J. A clinician’s guide to Australian venomous bites and stings: Incorporating the updated CSL antivenom handbook. Melbourne: CSL Ltd, 2012

Dr Neil Long BMBS FACEM FRCEM FRCPC. Emergency Physician at Kelowna hospital, British Columbia. Loves the misery of alpine climbing and working in austere environments (namely tertiary trauma centres). Supporter of FOAMed, lifelong education and trying to find that elusive peak performance.