Bloody Diarrhoea

aka Tropical Travel Trouble 004

A medical student who has just returned from their elective in Nepal presents with 1 week of bloody diarrhoea. He had been in the lowlands and stayed with a family in the local village.

The diarrhoea started three days prior to leaving Nepal, but is getting worse. He is now opening his bowels 10x a day with associated cramps, fevers and has started feeling dizzy.

Q1. What is dysentery and what is your differential?

Answer and interpretation

Dysentery is simply diarrhoea with blood – it is usually associated with fever but this is not always the case.

Sir William Osler described dysentery as “One of the four great epidemic diseases of the world”. He further stated “In the tropics it destroys more life than cholera, and it has been more fatal to armies than powder and shot.”

While the differential is moderately large, most commonly amoebic dysentery (E.histolytica) and bacillary dysentery (shigellosis) are the most prevalent. [Reference]

Differentials include:

- Bacterial:

- Gram positive – Clostridium Difficile

- Gram negative – Shigellosis, Enterohaemorrhagic E.coli, Salmonella, Yersinia enterocolitica

- Protozoa – Entamoeba histolytica, Balantidium coli

- Helminths – Schistoma (S. mansion or S. japonicum), Ascariasis, Trichuriasis

- Non-infectious – inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer, polyps, ischaemic colitis

Q2. What tests would you order to help narrow the differential?

Answer and interpretation

Stool MC+S, cysts, ova and parasites are commonly requested but routine microscopy of fresh stool is a simple screening test to detect invasive bacterial diarrhoea. It is cheap, rapid and easy to perform, even in a peripheral health facility.

A fresh stool wet mount will allow any lab to detect the protozoan cysts and trophozoites (E.histolytica, E.coli, Giardia, Balantidium coli). They will also see the eggs of the schistoma, ascariasis, trichuriasis and other helminths.

The identification of numerous PMNs suggest a bacterial aetiology, but does not distinguish shigellosis from disease caused by other invasive bacteria, such as Campylobacter jejuni.

Some laboratories are now using automated polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnostics on stool. These systems typically have the capability to identify any of multiple enteric bacterial pathogens from a homogenized stool sample in a few hours. However, they are not able to assess antimicrobial susceptibility of identified pathogens.

Stool microscopy shows leukocytes but no trophozoites or cysts (amoebic dysentery, e.coli, giardia, B.coli), no helminth eggs. The patient has no PMH and no prior antibiotic use. Given his travels and knowing that amoebic dysentery or shigella is most likely you suspect shigella.

Q3. Who is the natural host for shigellosis? And what is the incubation period?

Answer and interpretation

Humans are the only natural host for shigella. There are four main infective species: S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. sonnei and S. boydii. They are gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, nonspore-forming, non-motile, rod-shaped bacteria genetically closely related to E. coli.

- As few as 10 colony forming units of S. dysenteriae can cause infection. The low infectious inoculum facilitates person-to-person spread by faecal–oral contact, which is the predominant mode of transmission. Flies can also disseminate the disease if there is faecal contamination in the environment.

- A definitive diagnosis of Shigella requires serotyping and culture to determine antimicrobial sensitivity as resistance can be common (this will be lab dependent).

- Inadequate sanitation and hygiene favour transmission.

- The incubation period is 1-4 days up to 8 days with S. dysenteriae.

Q4. Who is at risk of Shigella?

Answer and interpretation

- Children aged 1-4 years living in resource-restricted settings or in daycare.

- Travellers to endemic areas (represents 9% of travellers’ diarrhoea).

- Men who have sex with men.

- Immunocompromised (HIV, steroids, immunosuppression)

- Malnourished

- Globally shigella is the second-leading cause of diarrhoea deaths after rotavirus, responsible for 164,300 deaths worldwide, of which 54,900 are children under 5 years of age.

Q5. What are the classic clinical features?

Answer and interpretation

Shigella was the major pathogen in dysentery (attributable fraction 63.8%), but it was also the second most common pathogen associated with watery diarrhoea (attributable fraction 12.9%). Enterotoxins are probable mediators of the watery diarrhoea often seen during the early stages—or as the sole manifestation—of shigellosis.

- It may also be asymptomatic in those that have had a prior infection (asymptomatic carriers).

- Typically patients present with a fever, headache, malaise, anorexia and vomiting with watery diarrhoea. If this is not self limiting, it can then progress onto dysentery, lower abdominal cramps and tenesmus with up to 20 stools per day.

- In shigella dysentery the frequency of signs are as follows:

- Fever 80%

- Abdominal cramps 81%

- Vomiting 18% (usually a later sign and more common in a patient with watery diarrhoea).

- Dehydration 13%

- Tenesmus 68%

- Rectal prolapse 3%

Q6. What are the complications of shigella?

Answer and interpretation

Intestinal complications:

- Rectal prolapse

- Toxic megacolon

- Perforation

- Obstruction

- Appendicitis

- Persistent diarrhoea

Extraintestinal complications:

- Dehydration

- Severe hyponatraemia

- Hypoglycaemia

- Focal infections (meningitis, osteomyelitis, arthritis, splenic abscess and vaginitis).

- Seizures (occur in 5-30% of admitted children) or encephalopathy (Ekiri syndrome).

- Leukaemoid reaction (peripheral leucocytes >40,000)

Post infectious manifestations:

- Haemolytic uraemia syndrome – is attributed to the prothrombotic effects of circulating shiga toxin, which binds to microvascular endothelial cells, resulting in microangiopathic haemolysis, azotemia, and neurological abnormalities.

- Reactive arthritis. This is an immune mediated seronegative spondylarthropathy that develops 1-4 weeks after shigella in about 1-2% of cases and resolves within 12 months.

- Irritable bowel syndrome (often resolves within 12 months).

- Malnutrition

Q7. What are your treatment options?

Answer and interpretation

The cornerstone of treatment is hydration and electrolyte balance.

- You may get away with oral rehydration as per the WHO formula.

- Antimotility agents are NOT recommended due to an increase risk of compensation and a prolonged period of bacterial shedding.

- Antibiotics for dysentery producing shigella is beneficial. It reduces the course of the illness by 1-2 days including bacterial shedding and thus reduces the risk of person-person transmission. Antibiotic use in watery diarrhoeal forms of shigella is less clear. Also given the implication of HUS you may have thought that antibiotic use should be with caution, however antibiotic use with shigella and HUS is very unclear with some studies suggesting it lowers the risk of HUS.

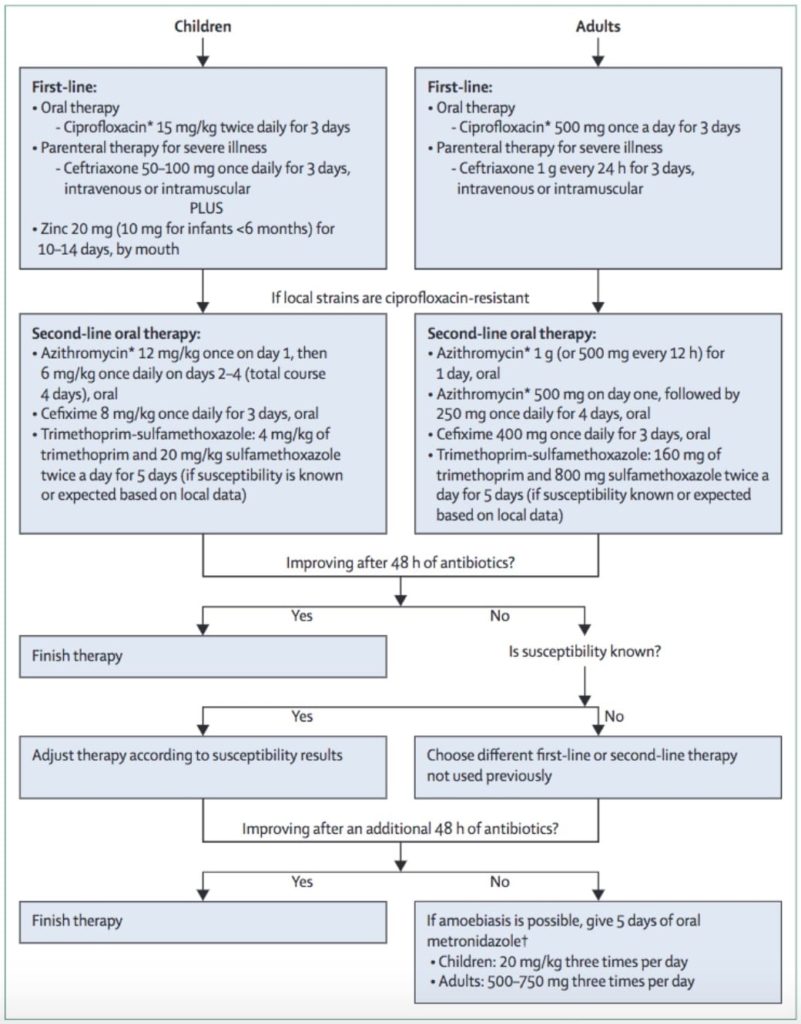

WHO 2015 guidelines:

- 1st line Ciprofloxacin 15mg/kg in paediatrics (max 500mg) and adults 500mg BD for 3 days.

- 2nd line Ceftriaxone 50mg/kg in paediatrics (max 1g) and adults 1g OD for 3 days

- Or:

- Azithromycin 12mg/kg on day 1 and 6mg/kg on days 2-4 in paediatrics. 500mg BD on day one for adults then 250mg for 4 days, Or:

- Pivmecillinam 20mg/kg in paediatrics (max 100mg) and adults 100mg QID for 5 days.

Antibiotics to avoid due to resistance: ampicillin, amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, tetracycline, nitrofurans, aminoglycosides, first and second generation cephalosporins and nalidixic acid.

Children: Oral zinc 20mg (10mg for infants <6 months) for 10-14 days. The role of vitamin A is not clear.

And for our Australian readers, Azithromycin is likely the best first line agent [MJA reference]

Bottom line (excuse the pun), know your antibiotic resistance, and use appropriate 1st line agents. Expect an improvement within 48hrs. If no improvement, check for sensitivities and resistance. Consider changing to a second line agent.

Q8. I’m going traveling, how do I prevent this, what about a vaccine?

Answer and interpretation

- Currently unavailable, but three vaccines are in trial so watch this space.

- The best prevention is good hand hygiene with soap or a dilute chlorine solution.

- Treat drinking water with chlorine or boiling is sufficient to kill shigella.

Case Resolution

Case Outcome

The patient was treated with azithromycin due to high resistance to ciprofloxacin in Nepal and made a full recovery 3 days later. Watch this space to see where he travels to next and what he catches!!

Quick Summary:

- Shigella is a common form of dysentery (along with amoebic dysentery).

- Stool microscopy in resource-poor settings will knock off most of the differential for bloody diarrhoea and you will likely see a report of lots of blood and polymers seen in the stool. If possible culture and sensitivity is important to order but you may be limited in the developing setting.

- Treat empirically as per local resistance (either ciprofloxacin or azithromycin) for those that the disease is not resolving, dehydrated, at risk or need hospitalisation.

- Cornerstone of treatment is hydration and electrolyte balance.

- Children also benefit from zinc therapy.

- Multiple complications can occur including: hyponatramia, hypoglycaemia, seizures, leukamoid reaction, HUS, rectal prolapse and reactive arthritis.

- Killed by boiling water and chlorine. Wash your hands with soap or chlorinated water.

References

- Beeching N and Gill G. Lecture Notes – Tropical Medicine. 7e Wiley Blackwell 2014.

- Eddleston, Davidson, Brent, Wilkinson. Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine. Oxford Medical Handbooks. 4e 2014

- Guidlines for the control of shigellois – WHO – 2015 (A good resource on how to manage an outbreak)

- Kotloff K et al. Shigellosis. Lancet Seminar Dec 2017.

- Matthews PC. Tropical Medicine Notebook. Oxford University Press, 2017

- Manatsathit S. Guideline for the management of acute diarrhoea in adults. J. Gastr and hep 2002

- Rothe C. Clinical Cases in Tropical Medicine. Elsevier 2015. ISBN 9780702058240

- Uptodate – Shigella

CLINICAL CASES

Tropical Travel Trouble

Dr Neil Long BMBS FACEM FRCEM FRCPC. Emergency Physician at Kelowna hospital, British Columbia. Loves the misery of alpine climbing and working in austere environments (namely tertiary trauma centres). Supporter of FOAMed, lifelong education and trying to find that elusive peak performance.