Claudius Amyand

Claudius Amyand (c.1680-1740) was a French-born English surgeon

Amyand was a Huguenot refugee from Paris who rose to become Serjeant-Surgeon to King George II and a pioneer of early modern surgery in London. Born into a Protestant family forced to flee France after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, he was naturalised in England in 1700 and built his career in the military and hospital practice.

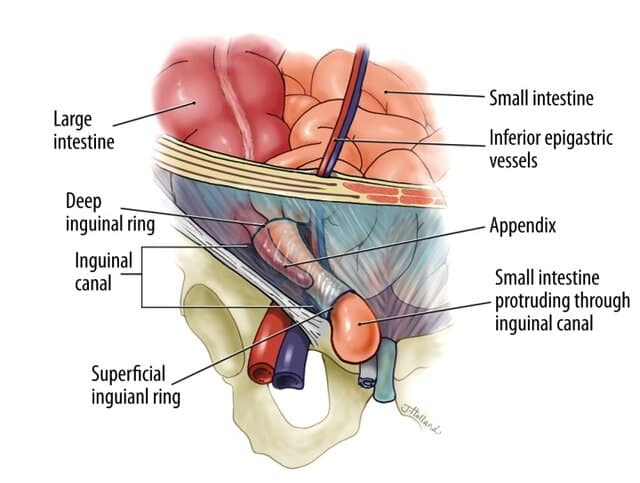

He is best remembered for performing, on December 6, 1735 at St George’s Hospital, the first recorded appendicectomy, removing a pin-perforated appendix during an operation for an inguinal hernia. The presence of the appendix within an inguinal hernia remains known as Amyand’s hernia. Nearly three centuries later, the association of Amyand’s hernia, appendicitis, and undescended testis was coined as Amyand’s triad.

Despite these achievements, aspects of Amyand’s legacy remain debated. A Gainsborough portrait long attributed to him is now thought to depict his son, Claudius Amyand junior (1718–1774), an MP and Keeper of the King’s Library. No authentic likeness of the surgeon is known, yet his place in surgical history is secure: a refugee who became royal surgeon, Fellow of the Royal Society, and the first to remove a human appendix.

Biographical Timeline

- c.1680 – Born at Mornac, Departement de la Charente, Poitou-Charentes, France second son of Isaac Amyand, a Huguenot refugee, and Anne Hottot. No formal records of birth.

- 1685 – Following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV, the Amyand’s fled France and settled in London. Issac was naturalised in 1688 along with many other Huguenot refugees.

- 1700 – Claudius received the sacrament on February 18, and was naturalised in London on April 11, suggesting he was around 16 at the time.

- 1704 – Served as apprentice surgeon in the War of the Spanish Succession; present at the Battle of Blenheim (13 August). Received £30 bounty for service.

- 1708 – Reported surgical cases from Ghent to the Royal Society, including “A Relation of an Idiot at Ostend,” published in Philosophical Transactions.

- 1715 – Commissioned Surgeon of Lumley’s Horse (First Dragoon Guards). Commission renewed in 1727 to continue until 1739.

- 1716 – Elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).

- 1717 – Married Mary Rabache, with whom he had three sons and six daughters, including Claudius Amyand junior (1718–1774), later MP and Keeper of the King’s Library.

- 1721–1722 – Assisted Princess Caroline of Ansbach and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in early smallpox inoculation experiments. Inoculated condemned prisoners and later the royal princesses Amelia and Caroline under the supervision of Sir Hans Sloane.

- 1721 – Appointed first Principal Surgeon to Westminster Hospital.

- 1727 – On the accession of George II, appointed Serjeant-Surgeon to the King.

- 1728 – Admitted to the Company of Barber-Surgeons; later Warden (1729–30) and Master (1731).

- 1734 – Appointed Principal Surgeon of St George’s Hospital, newly opened at Lanesborough House, Hyde Park Corner.

- 1735 – On December 6, performed the first recorded appendicectomy at St George’s Hospital, removing a perforated appendix from 11-year-old Hanvil Anderson during surgery for a scrotal hernia.

- 1736 – Elected Governor of St George’s Hospital.

- Died July 3, 1740 following a fall and head injury

Medical Eponyms

Amyand’s hernia (1735)

Amyand’s hernia describes the presence of the vermiform appendix within an inguinal hernia sac, whether inflamed or not. Case reports range from incidental finding to incarcerated hernia with appendicitis or perforation. Management depends on appendix status (normal vs inflamed) and degree of contamination; mesh is avoided in infected fields.

Reported prevalence of Amyand’s hernia is 0.4–0.6% of all inguinal hernias, with appendicitis within an Amyand hernia in ~0.07–0.13%. In children, prevalence may reach ~1%. There is a male predominance (≈90% in reviews) and often right-sided due to anatomical predisposition.

Historical Significance

This was the first recorded appendicectomy. It was performed by Amyand, on December 6, 1735 at St George’s Hospital, London. The patient was Hanvil Anderson, an 11-year old male with an inguinal hernia and faecal fistula.

At operation, Amyand found a perforated appendix (penetrated by a swallowed pin); within the inguinal canal which he excised.

This Operation proved the most complicated and perplexing I ever met with…greatly disturbed by the Discharge of Faeces coming out of the Gut…which brought in View the Aperture made in it by the Pin hitherto concealed, through which that Part of it, which was incrusted with Chalk, had just made its way out upon an occasional Pressure, as a Cork out of a Bottle.

The Pin frequently lying in the way of the Knife, and starting out of the wounded Gut, as a Shot out of a Gun…It was the opinion of the Physicians and Surgeons present, to amputate this Gut: To which End a circular Ligature was made…That the Appendix Coeci should be the only Gut found in this Rupture, is a Case singular in Practice.

Amyand 1735

It is worth exploring other eponymous hernia adventures such as:

- Littre’s hernia (Meckel’s diverticulum in a hernia).

- de Garengeot hernia (appendix in femoral hernia) in 1731

- Richter’s hernia (partial bowel wall incarceration).

Amyand’s Triad (2018)

- Amyand’s hernia

- Appendicitis

- Undescended testis

2018 – Coined by Dhanasekarapandian, Shanmugam and Jagannathan who published the case of a 35-day-old infant with an irreducible right inguinal hernia, inflamed appendix, and gangrenous undescended testis managed by appendicectomy, orchidectomy, and herniotomy.

The authors noted the incidence of Amyand’s hernia in children as 0.07–0.28%, and with inflamed appendix ≈0.08%. They cite one other reported case of an Amyand’s hernia with appendicitis and undescended testis, that of a 26-day-old neonate with an inguinal hernia containing a perforated appendix that clinically mimicked testicular torsion of an undescended testis. The patient required an appendicectomy and orchidopexy [Kumar et al 2008]

We would like to name this rare triple association as “The Amyand’s triad” with the components being Amyand’s hernia, appendicitis, and undescended testis.

Dhanasekarapandian et al, 2018

Controversies

Early Life, Huguenot Refuge, and Naturalisation

Claudius Amyand was born c.1680–1684 in Paris to Isaac Amyand and Anne Hottot, members of a French Protestant (Huguenot) family. Huguenots were French Protestants following the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition.

In 1685, following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV, Protestants lost their civil and religious freedoms, facing forced Catholic conversion, exile, or persecution. This forced thousands of Huguenots into exile; the Amyands fled to London, where Isaac was naturalised in 1688.

Claudius himself was naturalised later, receiving the sacrament of the Church of England on February 18, 1700, and formally naturalised on April 11, 1700. Under the requirements of the Act, he must have been at least 14 years old at that date, fixing his birth between 1681–1684.

Many secondary sources give 1688 as Claudius’s own naturalisation date, but this in fact refers to his father Isaac. Primary evidence confirms that 1700 is the correct year for Claudius’s naturalisation.

The Portrait Controversy

For many years a portrait attributed to Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788) has circulated under the name of “Claudius Amyand.” Auction records (Christie’s, 1921; Sotheby’s, 2000) list the sitter simply as Claudius Amyand, without dates of birth or death. The painting shows a man in a dark blue coat with gold edging, a style consistent with Gainsborough’s London portraiture of the 1760s–1770s.

Chronologically it is highly unlikely to be of Claudius Amyand senior (c.1680–1740) with Gainsborough being only 13 at the time of Amyand senior’s death. Gainsborough painted almost exclusively from life and there is no evidence of an earlier likeness or sketch on which such a posthumous portrait could have been based.

The sitter therefore aligns far more convincingly with Claudius Amyand Jr (1718–1774), Amyand’s eldest son, who served as a Member of Parliament and Keeper of the King’s Library. He lived into the period when Gainsborough was active and would have been a typical client for a society portrait.

Conclusion: The Gainsborough portrait almost certainly represents Claudius Amyand Jr (1718–1774). No authentic portrait of Claudius Amyand Sr (the surgeon) is currently known.

Date of Death

Most secondary accounts state that Claudius Amyand, Serjeant-Surgeon to George II, died on July 6, 1740 or occasionally July 7, 1740. However, a contemporary report in the Derby Mercury (July 10, 1740) records that Amyand suffered a fall in Greenwich Park on Saturday July 2, 1740 and died the following morning, Sunday July 3, 1740, at his home in Castle Street, Leicester Fields.

[On Saturday July 2, 1740] Claudius Amyand, Esq; principal Surgeon to his Majesty, had the Misfortune to fall with his Head on a Stone as he was walking in Greenwich-Park, and although all proper Care was taken, he died of the Bruise he received by his fall on Sunday Morning, at his House in Castle-street, near Leicester Fields.

Derby Mercury July 10, 1740

Parish registers confirm that he was buried on July 11, 1740, and his will was proved on July 9, 1740, further supporting the earlier death date. The most consistent reconstruction is:

- July 2, 1740 – Fall in Greenwich Park with head injury

- July 3, 1740 – Death at home the following morning

- July 9, 1740 – Will proved.

- July 11, 1740 – Burial.

Major Publications

- Amyand C. A relation of an idiot at ostend; with two other chirurgical cases. Communicated to the Royal Society by Mr. de la Fage. Philos. Tr. R. Soc. London, 1708, 26: 170-174.

- Amyand C. VIII. Three cases communicated by Claudius Amyand, Esq; F. R. S. Serjeant Surgeon to his Majesty. – I. Concerning a child born with the bowels hanging out of the belly. – II. Of an extraordinary cause of a suppression of urine in a woman. – III. Of a stricture in the middle of the stomach in a girl, dividing it into two bags. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1732; 37: 258–260

- Amyand C. VIII. An Extraordinary Case of the Foramen Ovale of the Heart, being found open in an Adult Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1735; 39: 172

- Amyand C. Of an inguinal rupture, with a pin in the appendix caeci, incrusted with stone; and some observations on wounds in the guts. Phil. Trans. R. Soc., 1736, 39: 329-336. [Amyand’s hernia]

- Amyand C. VII. Of an obstruction of the biliary ducts, and an impostumation of the gall-bladder, discharging upwards of 18 quarts of bilious matter in 25 Days, without any apparent defect in the animal functions, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1738; 40: 317–325

- Amyand C. Of a bubonocele or rupture the groin, and the operation made upon it, Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1738; 40: 361–367

- Amyand C. VI. Of an iliac passion, occasioned by an appendix in the ilion: By the late Claudius Amyand Esq; Serjeant-Surgeon to His Majesty, and F. R. S. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1745; 43: 369–370

- Amyand C. V. Some observations on the spina ventosa. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1746; 44: 193–211

References

Biography

- Extract of a letter from Bordeaux July 9th. The Derby Mercury, Sun, 10 Jul 1740 page 3

- Claudius Amyand. The history of St. George’s Hospital. 1910: 288-290

- Claudius Amyand. Annals of the Barber-Surgeons 1890: 565

Eponymous terms

- Creese PG. The first appendectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1953 Nov;97(5):643-52.

- Hutchinson R. Amyand’s hernia. J R Soc Med. 1993 Feb;86(2):104-5.

- Kumar R, Mahajan JK, Rao KL. Perforated appendix in hernial sac mimicking torsion of undescended testis in a neonate. J Pediatr Surg. 2008 Apr;43(4):e9-10.

- Sengul I, Sengul D, Aribas D. An elective detection of an Amyand’s hernia with an adhesive caecum to the sac: Report of a rare case. N Am J Med Sci. 2011 Aug;3(8):391-3.

- Singal R, Gupta S. Amyand’s Hernia – Pathophysiology, Role of Investigations and Treatment. Maedica (Bucur). 2011 Oct;6(4):321-7.

- Ivanschuk G, Cesmebasi A, Sorenson EP, Blaak C, Loukas M, Tubbs SR. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Med Sci Monit. 2014 Jan 28;20:140-6.

- Michalinos A, Moris D, Vernadakis S. Amyand’s hernia: a review. Am J Surg. 2014 Jun;207(6):989-95.

- Dhanasekarapandian V, Shanmugam V, Jagannathan M. Amyand’s Hernia, Appendicitis, and Undescended Testis: The Amyand’s Triad. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2018 Jul-Sep;23(3):169-170. [Amyand’s Triad]

- Manatakis DK, Tasis N, Antonopoulou MI, Anagnostopoulos P, Acheimastos V, Papageorgiou D, Fradelos E, Zoulamoglou M, Agalianos C, Tsiaoussis J, Xynos E. Revisiting Amyand’s Hernia: A 20-Year Systematic Review. World J Surg. 2021 Jun;45(6):1763-1770.

- Dunea G. Claudius Amyand (c. 1680–1740) of the first appendectomy Hektoen International 2023

- Stick a Pin in It: Amyand Revisited. ACS Case Reviews. 2024

- Zhang L, Chen Z, Fu Y, Zhang Q, Hu H. Amyand’s hernia: a case report and literature review. Front Pediatr. 2025 Jul 9;13:1637375.

- Cadogan M. Eponymous triads, tetrads and pentads. LITFL

Eponym

the person behind the name

BSc (Hons) MBBS, St George’s University of London. Foundation training at St George's University Hospitals NHS Foundation trust and Kingston NHS Foundation trust. RMO in Emergency Medicine at the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth preparing for emergency training. When I'm not working I enjoy spending my time outdoors sailing, diving and hiking and hope to combine these passions with my career, pursuing interests in expedition and barometric medicine within my ED work.

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |