Peter Safar

Peter Josef Safar (1924-2003) was an Austrian physician, innovator, educator and humanist.

Safar’s work earned him recognition as the “father of modern resuscitation” and “founder of critical care medicine.” He was the driving force behind mouth-to-mouth ventilation, the development of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and the establishment of intensive care units. His career embodied both scientific rigour and humanitarian commitment, spanning anaesthesiology, resuscitation science, emergency medicine, and disaster preparedness.

His landmark contributions began with the demonstration that expired-air ventilation could safely and effectively oxygenate patients, laying the foundation for rescue breathing. Working with James Elam, William Kouwenhoven, James Rude and colleagues, he integrated artificial ventilation with closed-chest cardiac massage to create modern CPR. He went further, advocating the systematic A–B–C sequence of resuscitation and later expanding it to include advanced and cerebral life support (CPCR). These insights shaped not only emergency response but also the way medicine approached the chain of survival.

Beyond CPR, Safar pioneered the first multidisciplinary intensive care units, trained the world’s first paramedics through Pittsburgh’s Freedom House Ambulance Service, and championed therapeutic hypothermia and suspended animation as strategies to protect the brain after cardiac arrest and trauma. Safar transformed resuscitation from improvisation into a discipline, saving countless lives worldwide.

Biographical Timeline

- Born on April 12, 1924 in Vienna, Austria, to Karl Safar M.D. (ophthalmologist) and Vinca Safar-Landauer, M.D (paediatrician).

- 1938–1943 – Austria annexed by Nazi Germany; Safar’s parents dismissed from posts due to his mother’s Jewish ancestry. Sent to forced labor in Bavaria; avoided conscription through deliberate aggravation of eczema.

- 1943 – Entered University of Vienna Medical School. Witnessed wartime starvation and battle trauma in Vienna, shaping his humanitarian ethos.

- 1948 – Graduated MD, University of Vienna.

- 1949 – Surgical scholarship to Yale University; began work in the United States.

- 1950 – Married Eva his lifelong partner. The couple emigrated to Pennsylvania with minimal resources.

- 1950–1956 – Trained in anesthesiology and critical care in the U.S.; joined Johns Hopkins Hospital.

- 1957 – Demonstrated effectiveness of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation combined with chest compressions; foundation of modern CPR.

- 1958 – Established one of the first U.S. Intensive Care Units at Baltimore City Hospital.

- 1966 – Helped develop the first U.S. paramedic emergency medical service in Pittsburgh (“Freedom House Ambulance Service”).

- 1979 – Founded the International Resuscitation Research Center (later the Safar Center for Resuscitation Research) at University of Pittsburgh.

- 1980s–1990s – Advanced concepts in “suspended animation” and therapeutic hypothermia for trauma and cardiac arrest patients.

- 1988 – Received Lasker Award for Public Service.

- 1992 – Death of his daughter, Elizabeth, from asthma, galvanized his advocacy for better emergency care for asthma and airway emergencies.

- 1996 – Awarded the American Heart Association’s Distinguished Achievement Award.

- Died August 3, 2003 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, aged 79, after 15 months battling cancer.

Medical Eponyms

Peter’s Laws for the Navigation of Life (1994)

In 1994, on the occasion of his 70th birthday Safar was presented with a framed set of laws by his friends and colleagues. They were titled ‘Peter’s Laws for the Navigation of Life‘ with the instructive subtitle ‘The Creed of the Sociopathic Obsessive Compulsive‘.

The laws are listed in his 1994 autobiography with a clear footnote. Laws #1–19 were not his own: they were a humorous compilation “discovered by Åke Grenvik,” with later additions by James Snyder and Peter Winter. Safar’s sole personal contribution was Law #22: “It is up to us to save the world.”

Key Medical Contributions

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

In the 1950s, a triad of discoveries converged to create modern resuscitation.

1954 – James Elam and colleagues proved that expired air was sufficient to sustain gas exchange in apneic, paralyzed patients:

Paralyzed patients ventilated with the operator’s expired air showed adequate oxygenation and carbon dioxide elimination.

Elam et al 1954

1957 – Safar built on this by demonstrating that airway maneuvers combined with mouth-to-mouth ventilation could reliably maintain life:

Expired air respiration is adequate to maintain life in apneic individuals if the airway is kept open.

Safar, Anesthesiology 1957

1960 – William Kouwenhoven, James R Jude, and Guy Knickerbocker introduced closed-chest cardiac massage:

External cardiac massage can maintain an artificial circulation sufficient to sustain life in man.

Kouwenhoven 1960

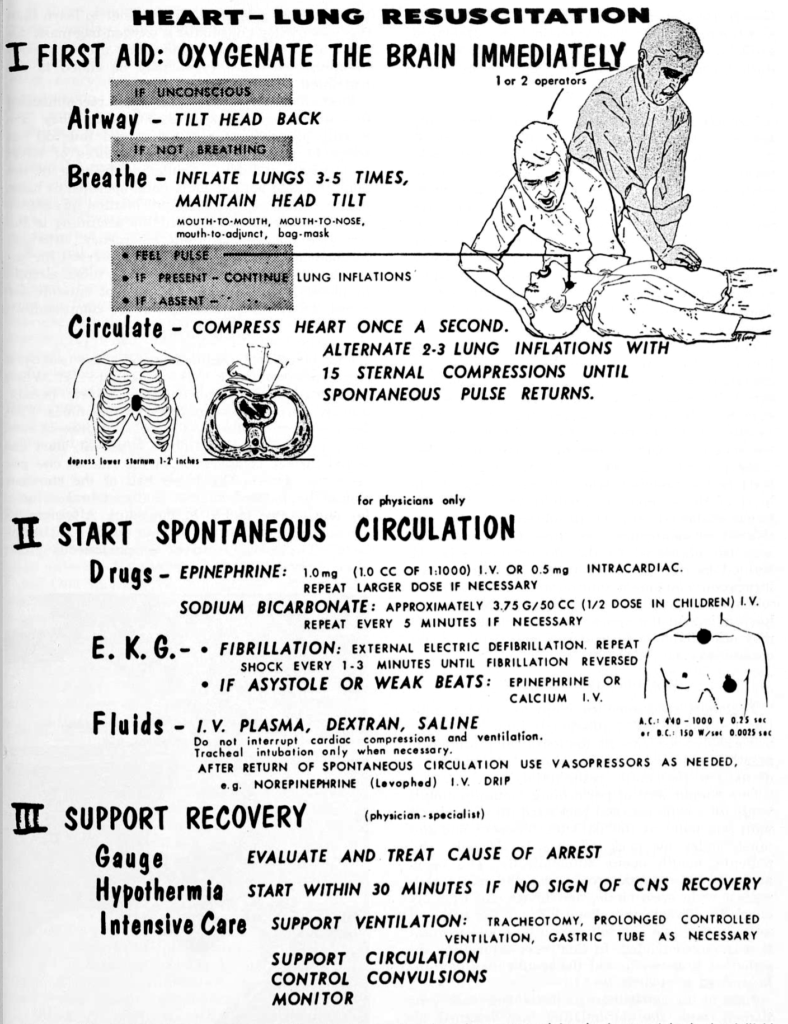

1961 – Safar articulated the sequence of Airway, Breathing, and Circulation as the clinical foundation of resuscitation.

By the fall of 1960, I already had conceptually extended the alphabet from steps A-B-C to steps D (drugs), E (electrocardiography), and F (fibrillation treatment) – transferred from open-chest CPR which together I called advanced life support (ALS). In 1961, I extended BLS and ALS further to prolonged life support (PLS), for which I extended the alphabet to step G (gauged), step H (humanized, brain oriented, and hypothermia [for cerebral resuscitation]), and step I (intensive care). In the early 1970’s I added “cerebral” and extended CPR to “cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation” (CPCR).

Safar, 1994

1962 – To spread the technique worldwide, Safar joined William Kouwenhoven and James Jude on a public campaign. During this tour, they enlisted director David Adams to create Pulse of life : the story of artificial respiration and artificial circulation, a 27-minute instructional film. For the first time, the letters A, B, C were used explicitly as a mnemonic to guide students and laypeople through the sequence.

1965 – Safar published an experimental study comparing various respiratory resuscitation techniques

Cardiopulmonary–Cerebral Resuscitation (CPCR)

Safar emphasized that resuscitation was not simply about restoring the heartbeat, but about protecting the brain. In the 1960s and 1970s he advanced the concept of cardiopulmonary–cerebral resuscitation (CPCR), combining airway, breathing, circulation, and therapeutic hypothermia to optimize neurological survival after cardiac arrest.

The object of CPCR is not merely to re-establish heartbeat and ventilation, but to preserve brain function. Without cerebral survival, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is a hollow success.

This cerebral focus distinguished Safar’s work from the narrower concept of CPR (cardiopulmonary resuscitation), which had gained traction after the 1960s. Over time, professional guidelines adopted CPR as the standard acronym, but Safar’s insistence on including the brain anticipated modern emphases on neuroprotective strategies and post-arrest care bundles.

Today, elements of Safar’s CPCR philosophy remain central with targeted temperature management, controlled oxygenation and ventilation, and structured post-resuscitation critical care. His holistic approach bridged the initial life-saving act of CPR with the long-term goal of meaningful neurological recovery.

The First Intensive Care Units (1958)

Peter Safar is widely regarded as one of the founders of modern intensive care medicine. In September 1958, he helped establish one of the first multidisciplinary intensive care units in the United States at Baltimore City Hospitals.

The ICU centralized critically ill patients under continuous observation, specialized teams, and advanced monitoring, improving survival in postoperative and emergency cases. This model became the prototype for ICUs across the United States and internationally, cementing Safar’s reputation as the “father of critical care medicine.”

In September 1958, the Department of Anesthesiology of the Baltimore City Hospitals in combination with the other clinical services and the nursing staff established an Intensive Care Unit. Initially this was an independent unit, but six months after its establishment … it was combined with the [surgical recovery ward].

Safar, 1961

By uniting airway management, ventilatory support, and circulatory stabilization within a dedicated ward, Safar’s ICU provided a new paradigm for critical care.

Freedom House and Paramedic Training

In 1966, Peter Safar helped launch the Freedom House Ambulance Service in Pittsburgh, the first U.S. program to train paramedics in advanced pre-hospital care. Partnering with civic leaders and community activists, Safar and colleagues recruited and trained unemployed African American men, equipping them with lifesaving skills that went far beyond the traditional “scoop and run” ambulance model.

The Freedom House paramedics were trained in airway management, CPR, defibrillation, drug administration, and trauma care. Despite facing skepticism and political resistance, their results were undeniable: patients treated by Freedom House paramedics had markedly higher survival rates than those transported by standard ambulance services.

Freedom House personnel demonstrated that non-physicians, when properly trained, could provide advanced life support outside the hospital, thereby transforming pre-hospital emergency care.

Although the service was eventually defunded in 1975, its legacy was profound, becoming the model for modern emergency medical services (EMS) across the United States and worldwide.

Rapid Sequence Induction (RSI)

In the early 1970s, Peter Safar and colleagues refined the practice of rapid sequence induction (RSI) as a method of securing the airway in critically ill patients at high risk of aspiration. RSI involved pre-oxygenation, administration of a rapidly acting sedative and neuromuscular blocker, and immediate tracheal intubation without bag-mask ventilation.

Safar promoted RSI as the safest way to induce anesthesia and control the airway in emergency and intensive care settings, where gastric aspiration and hypoxemia posed lethal threats. His protocols combined pharmacology with careful positioning and airway preparation, establishing a reproducible, lifesaving sequence still considered the gold standard in emergency and trauma care today.

The single most important duty of the physician in emergency anesthesia is to secure the airway promptly and protect the lungs from aspiration…A fifteen-step method of induction and intubation for avoiding aspiration of gastric contents has been used successfully in 80 patients over a 2-year period, and is described.

Safar 1970

Safar original RSI protocol (1970)

- Start intravenous infusion.

- Check equipment, including tracheal tube, cuff, stylet (for control of tube in emergency to avoid risking failure with the first attempt at intubation), adapters, oxygen source, bag-mask, and suction turned on, with a large-bore, rigid pharyngeal suction tip near the patient’s head.

- Insert a large-bore nasogastric tube and decompress the stomach with intermittent strong suction, to correct abdominal distention.

- Clean mouth and pharynx of foreign material, including dentures.

- Denitrogenate the lungs with 100 percent oxygen for at least 2 minutes, using a nonrebreathing system or a semiclosed-circuit system with over 10 L./min. flow and tight mask fit. Continue oxygen inhalation until intubation.

- Place patient in semisitting, V-position, with trunk elevated about 30 degrees, to counteract regurgitation by gravity, and feet elevated to prevent postural hypotension. Place pillow under occiput to support the head in the “sniffing” position for intubation.

- Apply electrocardiographic electrodes for monitoring the heart.

- Inject d-tubocurarine (3 mg/70 kg. body weight) intravenously.

- Give a predetermined dose of thiopental (e.g. 150 mg/70 kg. body weight) intravenously, about 2 minutes after injection of d-tubocurarine.

- Tilt the patient’s head gently backward with the onset of unconsciousness, and have an assistant apply and maintain firm, continuous cricoid pressure to close the oesophagus until the tracheal tube cuff is inflated at step 13.

- Inject succinylcholine chloride intravenously 100 mg/70 kg. body weight, immediately after the thiopental or the onset of unconsciousness

- Allow respiration to cease spontaneously. Apnea is essential, since partial paralysis would result in straining and regurgitation.

- Remove the mask while sustaining cricoid pressure, expose the larynx, and intubate the trachea rapidly; then inflate the cuff.

- Release cricoid pressure; ventilate; switch to maintenance anaesthetic.

- Insert a gastric tube, if one is not already in place.

Safar’s systematic teaching of RSI, first in the operating theatre and later in ICUs and EMS training, linked anesthesiology directly to modern emergency medicine.

Therapeutic Hypothermia and Suspended Animation

Peter Safar was among the first to imagine that cooling the body could extend the window for survival in cardiac arrest and trauma.

In the 1950s–60s, he experimented with therapeutic hypothermia to protect the brain during and after resuscitation. While early attempts at deep hypothermia led to complications, Safar demonstrated that moderate cooling after resuscitation could reduce neurological injury, foreshadowing what is now standard in post–cardiac arrest care.

By the 1990s, his work evolved into the idea of “suspended animation” for otherwise fatal haemorrhage inducing profound hypothermia in exsanguinating trauma patients to “buy time” for surgical repair. His experimental models on dogs cooled to 10 °C, exsanguinated, and later resuscitated was groundbreaking. Safar candidly described these studies as “science fiction made real,” yet they inspired decades of translational research.

We dared to ask whether the dying could be cooled into a state of suspended animation, giving surgeons an hour or more to repair lethal injuries. What had once seemed fantasy began to look like physiology.

The program I grew from my conviction that there are not only many “hearts too good to die“, but also many “brains too good to die.” In the 1980s, over half of our center’s effort was devoted to searching for a breakthrough in cerebral resuscitation after prolonged cardiac arrest

Today, both targeted temperature management after cardiac arrest and experimental emergency preservation and resuscitation (EPR) in trauma echo Safar’s vision. The once “radical” concept of suspended animation is now being trialed in humans.

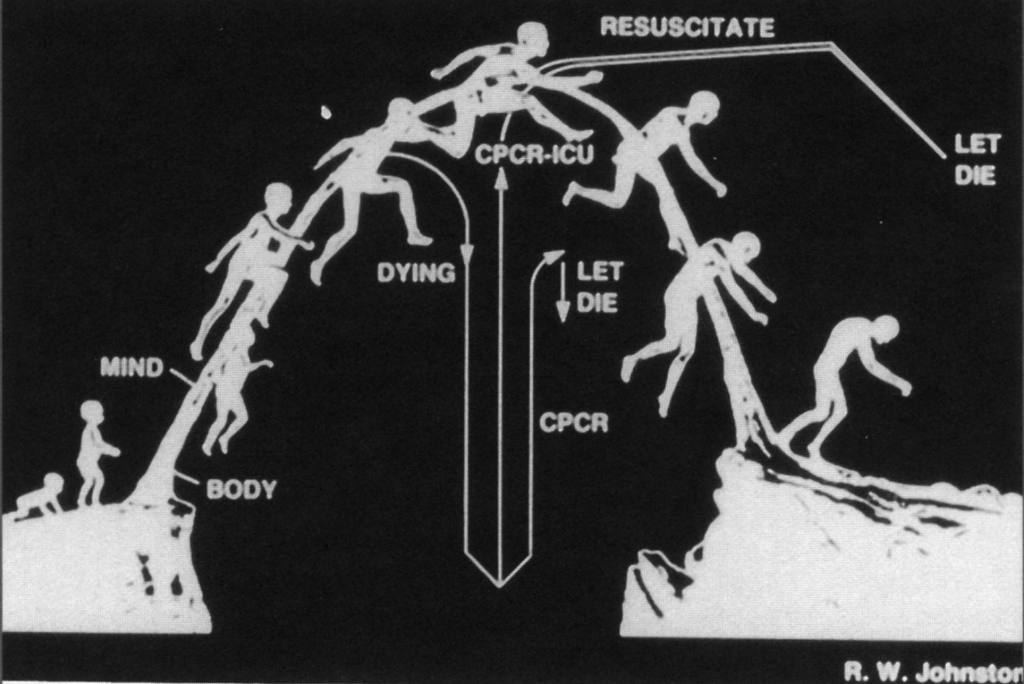

Nine Ages of Man

Safar modified the sculpture by Canadian artist R.W Johnston to describe the philosophy of resuscitation medicine. It focuses on the individual, whose arc of life is acutely interrupted by a natural or man-made insult in the absence of a lethal incurable disease, and before severe senile dementia. In old physical age, the mind can continue to advance.

Sculpture “Nine Ages of Man,” by Canadian artist R.W Johnston, a gift from the Department of Anesthesiology (Peter Winter) to the School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, on Peter Safar’s 60th birthday. [CPCR, cardiopulmonary cerebral resuscitation; ICU, intensive care unit.]

When an individual’s life is cut short unexpectedly (downward moving arrow), before his/her mind has declined (right upper corner of picture), all-out emergency resuscitation should be attempted. When, during subsequent prolonged life support, efforts clearly will not achieve a chance for a good cerebral outcome, death should be permitted. When the mind has a chance to recover long-term expensive intensive care is justified. When an old person has decided that the time has come, or is severely demented or unresponsive, and develops a sudden terminal state or cardiac arrest, resuscitative efforts are not justified.

Safar, 1994

Major Publications

- Safar P. Mouth-to-mouth airway. Anesthesiology. 1957 Nov-Dec;18(6):904-6.

- Safar P, Escarraga L, Elam J. A comparison of the mouth-to-mouth and mouth-to-airway methods of artificial respiration with the chest-pressure arm-lift methods. N Engl J Med. 1958 Apr 3;258(14):671-7.

- Safar P. Ventilatory efficacy of mouth-to-mouth artificial respiration; airway obstruction during manual and mouth-to-mouth artificial respiration. J Am Med Assoc. 1958 May 17;167(3):335-41.

- Safar P, McMahon MC. Resuscitation of the unconscious victim: a manual for rescue breathing. CC Thomas. 1959.

- Safar P, Redding J. The “tight jaw” in resuscitation. Anesthesiology. 1959 Sep-Oct;20:701-2.

- Safar P, Dekornfeld TJ, Pearson JW, Redding JS. The intensive care unit. A three year experience at Baltimore city hospitals. Anaesthesia. 1961 Jul;16:275-84

- Safar P. Community-wide cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J Iowa Med Soc. 1964 Nov;54:629-35.

- Stept WJ, Safar P. Rapid induction-intubation for prevention of gastric-content aspiration. Anesth Analg. 1970 Jul-Aug;49(4):633-6. [Original RSI paper]

- Safar P, Grenvik A. Organization and physician education in critical care medicine. Anesthesiology. 1977 Aug;47(2):82-95.

- Safar P. Cardiopulmonary Cerebral Resuscitation. AS Laerdal. 1981

- Safar P. Long-term animal outcome models for cardiopulmonary-cerebral resuscitation research. Crit Care Med. 1985 Nov;13(11):936-40.

- Safar P, Bircher NG. Cardiopulmonary–Cerebral Resuscitation: An Introduction to Resuscitation Medicine. London: WB Saunders; 1988 (3e)

- Safar P. Initiation of closed-chest cardiopulmonary resuscitation basic life support. A personal history. Resuscitation. 1989 Oct;18(1):7-20.

- Safar PJ. Careers In Anesthesiology: An Autobiographical Memoir. 1994 (Volume 5)

- Bellamy R, Safar P et al. Suspended animation for delayed resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 1996 Feb;24(2 Suppl):S24-47.

References

Biography

- Lenzer J. Peter Josef Safar. BMJ. 2003 Sep 13;327(7415):624

- Mitka M. Peter J. Safar, MD: “father of CPR,” innovator, teacher, humanist. JAMA. 2003 May 21;289(19):2485-6

- Stoy W, Grandey JT. Teacher, clinician … friend. Tributes to Peter Safar. JEMS. 2003 Oct;28(10):20-4.

- Acierno LJ, Worrell LT. Peter Safar: father of modern cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Clin Cardiol. 2007 Jan;30(1):52-4.

Eponym

- Elam JO, Brown ES, Elder JD Jr. Artificial respiration by mouth-to-mask method; a study of the respiratory gas exchange of paralyzed patients ventilated by operator’s expired air. N Engl J Med. 1954 May 6;250(18):749-54.

- Kouwenhoven WB, Jude JR, Knickerbocker GG. Closed-chest cardiac massage. JAMA. 1960 Jul 9;173:1064-7.

- Jude JR, Kouwenhoven WB, Knickerbocker GG. Cardiac arrest. Report of application of external cardiac massage on 118 patients. JAMA. 1961 Dec 16;178:1063-70.

- Meltzer ME, Benson D. Life in your hands [MOVIE]. Smith, Kline & French Laboratories 1961

- Jude JR, Kouwenhoven WB, Knickerbocker GG. External cardiac massage [MOVIE]. Smith, Kline & French Laboratories 1961

- Safar P, Jude JR, Kouwenhoven WB. Pulse of life : the story of artificial respiration and artificial circulation [MOVIE]. 1962

- Baskett PJ. Peter J. Safar, the early years 1924-1961, the birth of CPR. Resuscitation. 2001 Jul;50(1):17-22.

- Baskett PJ. Peter J. Safar. Part two. The University of Pittsburgh to the Safar Centre for Resuscitation Research 1961-2002. Resuscitation. 2002 Oct;55(1):3-7.

- Martens P, Mullie A. (Some of the) lessons learned from Peter Safar. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003 Dec;10(4):257.

- Delooz H. International emergency medicine: the vision of a pioneer, Prof. Dr Peter Safar, on emergency medical care. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003 Sep;10(3):163

- Edwards ML. Pittsburgh’s Freedom House Ambulance Service: The Origins of Emergency Medical Services and the Politics of Race and Health. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2019 Oct 1;74(4):440-466.

Eponym

the person behind the name

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |