Gut under pressure

aka Gastrointestinal Gutwrencher 005

One day, in the only hospital close to here, you are doing your ICU ward round – alone again, because the consultant has been “called away” to an “urgent meeting” – probably at the coffee shop flirting with the ICU physiotherapist again…

Your first patient is a 68 year-old man, who is day 1 post-op laparotomy for perforated duodenal ulcer. They had difficulty closing the abdomen, but with some 1.0 nylon and some good strong knots they managed to appose the wound edges.

(“uggh…must…close…abdomen…grunt…at…all…costs…”)

Overnight the patient has become anuric, and the nurse comments to you that the abdomen feels tight. Being an ICU doctor, you shudder at the thought of actually touching a patient, and instead start fingering through the notes, looking at the ventilator settings and latest blood gas results.

The nurse interrupts your dithering, and says. “Do you think the abdominal pressure might be a bit too high?”

“Hmmm”, you say thoughtfully, frantically trying to remember the normal abdominal pressures, and the consequences of high intraabdominal pressures. “You might be right…”

Questions

Q1. What is the normal intra-abdominal pressure?

Answer and interpretation

The normal intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) is between 5-7 mmHg.

In obese persons normal can range from 9-14mmHg.

Q2. What is intra-abdominal hypertension?

Answer and interpretation

Intra-abdominal hypertension (IAH) is an IAP ≥ 12 mmHg.

There are 4 grades of IAH.

- Grade I — 12-15 mmHg

- Grade II — 16-20 mmHg

- Grade III — 21-25 mmHg

- Grade IV — >25 mmHg

Q3. When does intra-abdominal hypertension become abdominal compartment syndrome?

Answer and interpretation

Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) requires NEW organ failure or dysfunction (especially renal) and an IAP >20 mmHg (i.e. Grade III or IV).

ACS occurs infrequently (5-12% of ICU patients), although IAH may be as common as 50%.

Q4. What causes ACS?

Answer and interpretation

ACS is a consequence of:

- decreased abdominal wall compliance (e.g. abdominal surgery esp tight closure or wall haematoma)

- increased abdominal volume (e.g. masses, fluid, colonic dilatation)

- or a combination of both (obesity, pancreatitis, sepsis/shock, burns, abdominal infection).

Primary ACS is due to an intra-abdominal cause whilst secondary ACS is due to an extra-abdominal cause, particularly overzealous fluid resuscitation. It is more common with major abdominal surgery or trauma.

This patient has now become anuric, having not passed urine for 4 hours. The creatinine has doubled.

The nurse asks you “I have felt his abdomen (for you) and it feels tight. Doesn’t this patient have Abdominal Compartment Syndrome?”

Knowing that clinical examination is unreliable in estimating IAP, you cunningly deflect her question, with a question of your own…

Q5. What question do you ask the ICU nurse?

Answer and interpretation

You ask the nurse, “What is his intra-abdominal pressure?” You get a blank look. Whew, finally some breathing space.

She replies, with another question of her own:

“Can you show me how to measure the abdominal pressure?”

Q6. How do you measure the intra-abdominal pressure?

Answer and interpretation

Intra-vesicular (intra-bladder) pressure has been shown to correlate accurately with intra-abdominal pressure.

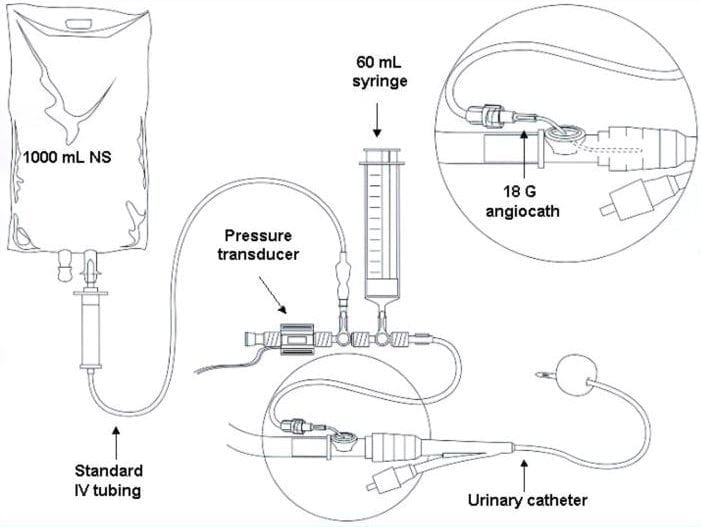

There are commercially available devices to measure IAP, however the most common method involves using a foley catheter (indwelling catheter) and a manometer.

You start by filling the patients’ empty bladder with 50-100ml of sterile saline through the catheter, then allowing the saline to flow back to the clamp. Occlude the catheter and use a Y-connector to attach a normal manometer. Zero the manometer with the patient supine at the midaxillary line or symphysis pubis, at the end of expiration.

So you take this reading and the IAP is 24mmHg.

Bingo.

The nurse is right (again). This patient has ACS. But so what?

Q7. What are the physiological consequences of IAH?

Answer and interpretation

IAH reduces splanchnic perfusion, resulting in ischaemia to abdominal organs leading to increased mucosal permeability and bacterial translocation from the GI tract. However renal impairment appears to be the most important physiological change, activating the renin, angiotensin and aldosterone pathways, and leading to acute kidney injury.

Other physiological consequences include:

- cardiovascular — increased central venous pressure, decreased venous return and decreased cardiac output

- respiratory — decreased thoracic compliance resulting in increased inspiratory pressures or decreased tidal volumes.

- intracranial — decreased cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP = MAP – ICP) due to cerebral oedema resulting from decreased venous return from the brain.

If ACS develops, mortality is high, approaching 50%.

Q8. What is the treatment for ACS?

Answer and interpretation

The mainstay of treatment may be urgent surgical decompressive laparotomy — so call the surgeons!

Conservative measures include:

- improve abdominal wall compliance —e.g. positioning (head up >20 degrees, avoid prone position), remove constrictive dressings, analgesia/ sedation, neuromuscular blockade

- decompress intraluminal contents — e.g. NG tube, rectal tube, enemas, prokinetics such as metoclopramide, erythromycin or neostigmine infusion, colonoscopic decompression

- treat intrabdominal space occupying lesions — e.g. paracentesis

- correct fluid overload — e.g. fluid restriction, diuresis, colloids, renal replacement therapy

- optimise abdominal perfusion pressure (APP = MAP – IAP): target APP > 70 mmHg: fluid resuscitation, vasopressors/ inotropes, invasive monitoring

Check out these algorithms from WSACS FOAM education resources (they are pdf downloads):

References

- Cheatham ML, Safcsak K. Intraabdominal pressure: a revised method for measurement. J Am Coll Surg. 1998 May;186(5):594-5. PMID: 9583702.

- Crashingpatient.com — Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

- De Waele JJ, De Laet I, Kirkpatrick AW, Hoste E. Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011 Jan;57(1):159-69. Review. PMID: 21184922.

- World Society of Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

CLINICAL CASES

Gastrointestinal Gutwrencher

Specialist Intensive Care Physician working at the Austin Hospital, Melbourne. Interests: Shoulder Dislocations, Pain Management, End-of-life care, Organ Donation and ECGs | Linkedin |