Joseph Jones

Joseph “Joe” Jones (1833-1896) was an American Confederate surgeon

Jones was a professor of chemistry, physiology, and pathology at Southern medical schools. His career shifted dramatically with the Civil War. Serving as a Confederate surgeon (1862–1865), Jones documented hospital gangrene in battlefield hospitals and prison camps, including Andersonville, estimating over 2,642 cases with nearly 50% mortality. His reports to Surgeon General Samuel P. Moore became foundational texts on gangrene, scurvy, and wound infection.

After the war, Jones became a dominant figure in Southern medicine and public health. He chaired Chemistry and Clinical Medicine at the University of Louisiana (later Tulane) from 1868 to 1895 and was visiting physician at Charity Hospital. His writings, notably the four-volume Medical and Surgical Memoirs (1876–1890), compiled decades of investigations on war injuries, malarial pathology, yellow fever, and sanitary reform. Jones served as President of the Louisiana State Board of Health (1880–1884), leading controversial battles over quarantine laws and national health authority, while implementing strict measures to exclude yellow fever from New Orleans.

Jones also made significant contributions to early microbiology, claiming to have observed the malarial parasite (1876) and typhoid bacillus (1862) years before their formal recognition by Laveran and Eberth. Though his interpretations were incomplete, his observations represented a “near-discovery” of key pathogens.

Biographical Timeline

- Born September 6, 1833 in Liberty County, Georgia.

- 1853 – Graduated B.A. and M.A., Princeton University.

- 1855 – Earned M.D., University of Pennsylvania; began teaching chemistry at Savannah Medical College.

- 1858–1860 – Professor of Natural Philosophy, University of Georgia; later Professor of Chemistry, Medical College of Georgia.

- 1861 – Commissioned as Confederate Army surgeon; later granted authority to inspect all Confederate hospitals.

- 1862–1865 – Conducted extensive research on hospital gangrene, tetanus, scurvy, malaria, and prison health; authored major Confederate medical reports.

- 1868 – Appointed Chair of Chemistry and Clinical Medicine, University of Louisiana; visiting physician at Charity Hospital, New Orleans.

- 1870 – Married Susan Rayner Polk after death of first wife; undertook European scientific tour.

- 1876–1890 – Published four volumes of Medical and Surgical Memoirs, including work on hospital gangrene and malarial pathology.

- 1878 – Claimed microscopic detection of malarial pigment in a medico-legal murder case (Arrieux murder), preceding Laveran’s parasite discovery.

- 1880–1884 – President, Louisiana State Board of Health; enforced quarantine laws during yellow fever epidemic; led high-profile disputes with the National Board of Health.

- 1887 – President, Section on Public and International Hygiene, Ninth International Medical Congress; asserted priority in malarial and typhoid discoveries.

- Died February 17, 1896 in New Orleans, aged 62.

Key Medical Contributions

Hospital Gangrene (Necrotizing Fasciitis)

During the American Civil War, Joseph Jones undertook a study of hospital gangrene, the devastating complication of gunshot wounds and amputations in overcrowded military hospitals. Working under direct authorisation from Confederate Surgeon General Samuel Preston Moore, Jones traveled extensively through field hospitals, prison camps, and major Confederate medical centres to observe, document, and analyse the disease.

He described the condition as characterised by rapid tissue destruction, foul-smelling necrosis, systemic toxaemia, and extremely high mortality. His clinical observations included meticulous post-mortem findings, blood and urine analyses, and histological examinations. Jones concluded that hospital gangrene was not due to a single agent but arose from a confluence of factors including devitalised tissue, poor sanitation, and environmental conditions conducive to “poisoned air.” His recommendations emphasised rigorous wound debridement, antiseptic dressings, isolation of infected cases, and improved ventilation.

These reports, later compiled in Medical and Surgical Memoirs and published in the Sanitary Memoirs of the United States Sanitary Commission (1871), influenced post-war surgical practice and served as a vital historical link to the later conceptualization of necrotizing fasciitis by Frank L. Meleney (1889–1963) in 1924 and Ben J. Wilson (1920–2015) in 1951.

The Arrieux Murder Case and the Near-Discovery of the Malarial Parasite

In December 1876, an elderly shopkeeper named Narcisse Arrieux was brutally murdered in Donaldsonville, Louisiana. During the investigation, one suspect, Wilson Childers, was found with reddish stains on his clothing, which he claimed were paint. The material was sent to New Orleans for expert analysis, where Jones, then Professor of Chemistry and Clinical Medicine at the University of Louisiana, performed detailed examinations and published his findings in 1878.

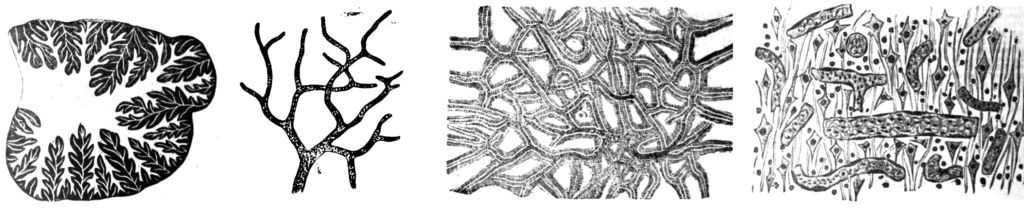

Using chemical tests and microscopic analysis, Jones confirmed that the stains were human blood rather than paint. More significantly, he observed abnormal structures in the blood that he interpreted as evidence of malarial infection in both the victim and the suspect. His microscopic descriptions included “black pigment or melanaemic corpuscles” and hyaline masses within red and white corpuscles, which are now recognized as features of Plasmodium infection. Jones concluded that the victim had been suffering from intermittent malarial fever at the time of death, a conclusion corroborated by witness testimony that Arrieux had experienced malarial symptoms for weeks prior to the murder.

I observed black pigment… in red globules and leucocytes, indicating malarial fever.

These observations, published two years before Alphonse Laveran’s definitive identification of the malarial parasite in 1880, place Jones among the first to document the microscopic features of the infection in human blood. His accompanying drawings, later reproduced in Medical and Surgical Memoirs (Vol. II, 1887), clearly illustrate forms corresponding to parasite stages within erythrocytes, as well as phagocytosed pigment within leukocytes (now known as malarial pigment). Despite this, Jones interpreted the structures as spore-like bodies from an environmental source, rather than as a parasitic protozoan transmitted by mosquitoes. This misinterpretation cost him the priority of discovery.

At the Ninth International Medical Congress (Washington, 1887), Jones laid formal claim to having first detected the malarial parasite, entering into the record his 1878 paper as evidence. He argued that his observations anticipated the discoveries of Laveran and others in Europe. While history has credited Laveran as the discoverer of the parasite, Jones’s medico-legal investigation of a Louisiana homicide remains a fascinating episode in medical history demonstrating how forensic science, clinical medicine, and emerging microbiology converged during the late 19th century.

Quinine and the Confederate Army

Jones regarded malaria as one of the greatest threats to the Confederate forces and devoted considerable effort to its prevention and treatment. Recognizing the endemic nature of “malarial fevers” in the swampy Southern terrain, he advocated for systematic administration of quinine prophylaxis to soldiers. In his writings, Jones asserted:

Sulphate of quinia administered during health is the best means of preventing chill and fever.

Southern Medical and Surgical Journal, 1861

He recommended that quinine be given in small daily doses to troops operating in malarial regions, a practice that prefigured later military prophylactic regimens. Jones also investigated indigenous botanical remedies as substitutes during periods of drug scarcity, highlighting resourcefulness in Confederate medical logistics. His work on quinine not only underscored the importance of chemoprophylaxis in military medicine but also reflected a broader transition in 19th-century therapeutic strategies from empirical remedies toward more systematic, pharmacologically grounded interventions.

Major Publications

- Jones J. Investigations, chemical and physiological, relative to certain American Vertebrata. 1856

- Jones J. Observations on some of the physical, chemical, physiological and pathological phenomena of malarial fever. 1859

- Jones J. Sulphate of Quinia administered in small doses during health, the best means of preventing Chill and Fever, and Bilious Fever, and Congestive Fever, in those exposed to the unhealthy climate of the rich low lands and swamps of the Southern Confederacy. 1861

- Jones J. Quinine as a prophylactic against malarial fever. 1864

- Jones J. Researches upon “spurious vaccination”. 1867

- Jones J. Mollities ossium : (malakosteon, osteo-malacia, osteo-sarcosis, Knochen-Erweichung, rachitismus adultorum, rickets, or softening of the bones in the adult). 1869

- Jones J. Outline of observations on hospital gangrene : as it manifested itself in the Confederate armies, during the American Civil War, 1861-1865. 1869 [necrotizing fasciitis]

- Jones J. Spontaneous combustion. 1874

- Jones J. Medico-legal Evidence relating to the detection of Human Blood presenting the alterations characteristic of Malarial Fever, on the clothing of a man, accused of the murder of Narcisse Arrieux, December 27th, 1876, near Donaldsonville. New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal 1878; 6: 139-156

- Jones J. Compulsory vaccination : the establishment of a uniform system of vaccination for all citizens and inhabitants of the state of Louisiana, by legislative enactment. 1878

- Jones J. Medical and surgical memoirs Volume II, 1887

- Jones J. Outline of investigations into the nature, causes and prevention of endemic and epidemic diseases, and more especially malarial fever, during a period of thirty years, with a claim to priority in the determination of the chemical and microscopical characters and changes of the blood in the various forms of malarial paroxysmal fever and the application of the results of these investigations to medical diagnosis and medical jurisprudence. Transactions of the International medical congress. Ninth session 1887

- Jones J. Medical and surgical memoirs Volume III, 1890

References

Biography

- Watson IA. Jones, Jospeh. Physicians and surgeons of America. 1896: 593-597

- Bayne-Jones S. Special article; Joseph Jones (1833-1896). The Bulletin of the Tulane Medical Faculty. 1958 May;17(3):223-30

- Jarcho S. Malaria and murder (Joseph Jones, 1878). Bull N Y Acad Med. 1968 Jun;44(6):759-60.

- Shayeb M. A Regional Affliction: a Portrait of Dr. Joseph Jones in the New South. 2017

- A Guide: Dr. Joseph Jones. Tulane University

Eponym

the person behind the name

BMedSci (infectious disease) MB ChB, Edinburgh University. Emergency Medicine training. Currently working at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Perth Austraslia.

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |