Marshall Hall

Marshall Hall (1790-1857) was an English physician, physiologist and humanitarian

Hall was a pioneering English physician, physiologist, and social reformer whose work reshaped 19th-century medicine and physiology. Educated at Edinburgh and deeply influenced by experimental science, Hall is best remembered for elucidating the reflex function of the spinal cord, a concept that revolutionized neurophysiology. His identification of the spinal cord as an “excito-motory” system anticipated the integration of physiology with clinical neurology and influenced figures such as Claude Bernard and Charles Sherrington.

Hall’s prolific career spanned physiology, pathology, and public health. He challenged the prevailing reliance on bloodletting, publishing landmark critiques that helped shift therapeutic practice. His experimental rigor extended to animal ethics, as he introduced the first formal principles for humane vivisection in 1835—decades before legislation on animal welfare.

Beyond the laboratory, Hall was a reformer and humanitarian. His “Ready Method” of resuscitation for drowning victims transformed lifesaving practice and inspired modern CPR. Yet his life was not without controversy: his combative style, strong opinions on slavery, and personal temperament brought him into repeated conflict with medical institutions and colleagues. A tireless advocate for scientific medicine and social responsibility, Hall died in 1857, leaving an enduring legacy that bridged clinical practice, experimental physiology, and public health reform.

Biographical Timeline

- Born on February 18, 1790 at Basford, near Nottingham, England

- 1804 – Apprenticed to a chemist in Newark, marking early scientific interest

- 1809 – Entered Edinburgh University to study medicine; excelled academically

- 1811 – Elected Senior President of the Royal Medical Society (Edinburgh)

- 1812 – Graduated MD Edinburgh with Dissertatio inauguralis de febribus inordinatis; appointed House Physician at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary

- 1814 – Traveled through Paris, Göttingen, Berlin to study medicine

- 1817 – Published On Diagnosis; settled in Nottingham as a physician

- 1825 – Published On Some Effects of Loss of Blood, challenging indiscriminate bloodletting; appointed physician to the Nottingham General Hospital

- 1826 – Moved to London, continued private practice; published Commentaries on some of the more important of the diseases of females

- 1831 – Published A critical and experimental essay on the circulation of the blood; early work on crush injury and shock

- 1832 – Discovery of reflex action (spinal cord as “excito-motory system”) via experiments on amphibians; concept rejected by Royal Society who refused to publish his papers; difficulty finding a physician appointment at any London hospital despite his previously high esteem.

- 1833–1837 Published series of papers on reflex action, leading to major physiological controversy

- 1835 – Published Principles of Investigation in Physiology; introduced 5 ethical rules for animal experimentation

- 1836 – Lectures on Nervous System and its Diseases; early description of sensory ataxia (predating Romberg)

- 1841 – Elected FRCP (London)

- 1842 – Delivered Goulstonian Lectures; began lecturing at St Thomas’s Hospital (1842–1846)

- 1842–1846 lecturer at St. Thomas’s Hospital

- 1850–1852 Delivered Croonian Lectures on the nervous system

- 1856 – Introduced the Marshall Hall “Ready Method” for resuscitation in drowning: postural artificial respiration without apparatus

- Died August 11, 1857 in Brighton, aged 67, after prolonged illness

Medical Eponyms

Marshall Hall ‘Ready Method’ of treating asphyxia (1856)

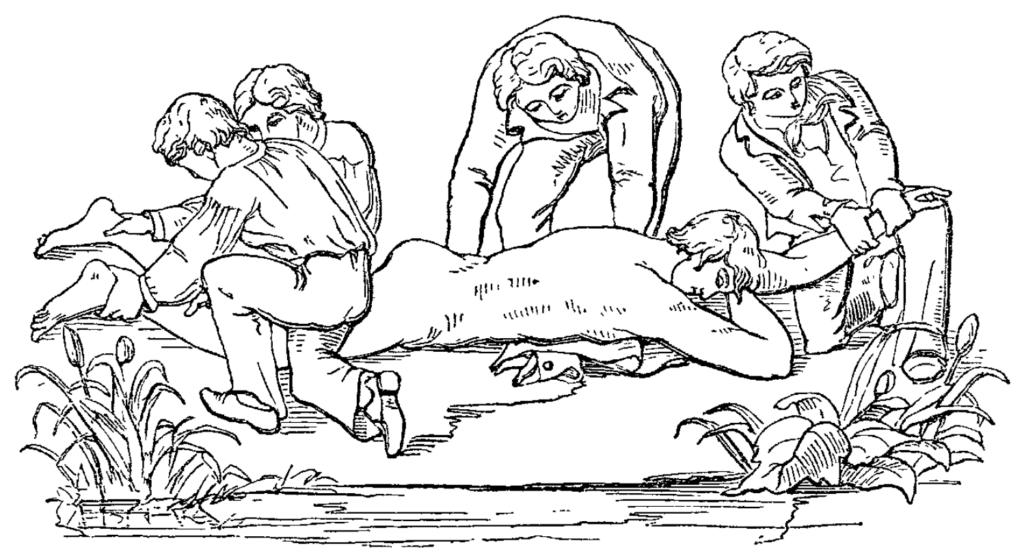

Hall’s most celebrated contribution to public health was his “Ready Method”—a postural technique for resuscitation in drowning and asphyxia. Rejecting the use of bellows and the warm bath, he emphasized prompt action on the spot. His method relied on alternate prone and side positioning to create natural respiration:

If there be one fact more self-evident than another, it is that artificial respiration is the sine qua non in the treatment of asphyxia, apnoea, or suspended respiration

Nothing can be more beautiful than this life-giving—if life can be given—breathing process

Marshall Hall, 1856

Hall’s Ready Method and 5 rules was adopted by the National Lifeboat Institution, though later supplanted by the Silvester method (1858).

Rule I: Remove obstruction of the glottis by placing the patient in the prone position with one wrist under the forehead

Rule II: Excite respiration physiologically (e.g. snuff or a dash of cold water to the face)

Rule III: Imitate the act of mechanical respiration; turn the body gently, but completely, on the side and a little beyond, and then on the face, alternately; repeating these measures deliberately, efficiently, and perseveringly, fifteen times in the minute

Rule IV: Induce circulation and warmth; rub the limbs upwards, with firm pressure and with energy to promote the flow of venous blood, and to restore warmth in the limbs

Rule V: Excite respiration once more; let the surface of the body be slapped briskly with the hand or, let cold water be dashed briskly on the surface previously rubbed dry

Key Medical Contributions

Romberg Sign (1836)

A decade before Romberg’s classic account, Hall described sensory ataxia and coordination deficits in spinal disease, linking these to reflex impairment. Hall recognized the compensatory role of vision but did not formalize this observation into a clinical test.

He walks safely while his eyes are fixed upon the ground, but stumbles immediately if he attempts to walk in the dark. His own words are: ‘My feet are numb; I cannot tell in the dark where they are, and I cannot poise myself

Though overshadowed by Romberg, Hall’s observations hinted at the clinical application of his reflex theory.

Crush Injury and Haemorrhagic Shock (1831)

Hall was among the first to recognize the physiological consequences of severe trauma and blood loss, describing systemic collapse following crush injuries. In A critical and experimental essay on the circulation of the blood (1831), he proposed that the body’s vital powers fail not only from haemorrhage but from nervous exhaustion and vascular collapse, foreshadowing modern concepts of shock:

The state of the system after great loss of blood, or after severe crushing of the limbs, exhibits a condition of profound prostration… the capillary circulation becomes arrested and the nervous system sinks into paralysis.

His work anticipated the later differentiation between neurogenic shock and hypovolaemic shock. Hall emphasized cautious transfusion and conservative measures. Radical ideas in an age dominated by aggressive venesection.

Reflex Action and the Spinal Cord (1832–1837)

Hall introduced the revolutionary concept of the reflex function of the spinal cord, which he termed the “excito-motory system.” Through meticulous experiments on decapitated animals, Hall demonstrated that the spinal cord could mediate involuntary movements independently of the brain.

The spinal system is an independent system, endowed with its own laws of action.

This work earned Hall recognition as a founder of modern neurophysiology and influenced the later work of Sherrington on the integrative action of the nervous system.

Reforming Bloodletting (1824)

In an era dominated by depletion therapy, Hall vigorously opposed indiscriminate bloodletting, advocating careful observation and moderation. His early work On Some Effects of Loss of Blood (1824) helped to displace a practice that had persisted for centuries.

Neurological landmarks (1841)

Marshall Hall recognized and described:

- the cerebrum as the source of voluntary motion;

- the medulla oblongata as the source of respiratory motion;

- the spinal cord as the middle arc of reflex function.

I incidentally observed a remarkable phenomenon; the separated tail of the eft [newt] moved on being irritated by the point of the scalpel … I conceived it impossible that any such phenomenon should exist in nature without such connection, and I resolved to pursue the subject

Marshall Hall 1841

Animal Welfare and Experimental Ethics (1835)

Hall introduced the first formal principles for humane vivisection, outlining five ethical rules (paraphrased):

- An experiment should never be performed if the necessary information can be derived from observations

- No experiment should be performed without a clearly defined, and obtainable, objective

- Scientists should be well-informed about the work of their predecessors and peers in order to avoid unnecessary repetition of an experiment

- Justifiable experimentation should be carried out with the least possible infliction of suffering (often through the use of lower, less sentient animals)

- Every experiment should be performed under circumstances that would provide the clearest possible results, thereby diminishing the need for repetition of experiments

This code predated legislative protection for animals by decades.

Controversies

Controversies and Temper

Hall’s uncompromising nature led to frequent disputes—with the Royal Society (over recognition for reflex theory), hospital boards, and contemporaries. His criticism of the Royal Humane Society’s resuscitation guidelines strained relations further, though his reforms were ultimately vindicated.

Slavery and Social Causes

Hall was outspoken on social issues, condemning slavery during his visit to the United States (1853–1854). He also campaigned for prison reform, abolition of corporal punishment, and public health improvements, demonstrating his humanitarian outlook beyond medicine.

Legacy

Hall’s insights transformed neurology, resuscitation, and medical ethics. His concept of reflex action laid the groundwork for modern neurophysiology. His Ready Method influenced early CPR techniques, and his advocacy for humane research foreshadowed animal protection laws.

Major Publications

- Hall M. On diagnosis, in four parts. 1817

- Hall M. On the reflex function of the medulla oblongata and the medulla spinalis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 1833; 123:635-65.

- Hall M. Observations on blood-letting founded upon researches on the morbid and curative effects of loss of blood. 1830

- Hall M. A critical and experimental essay on the circulation of the blood. 1831 [Crush injury and Haemorrhagic shock]

- Hall M. On the reflex function of the medulla oblongata and medulla spinalis. 1833

- Hall M. Lectures on the nervous system and its diseases. London. 1836 [Romberg Sign]

- Hall M. Memoirs on the nervous system. London, Sherwood, Gilbert, & Piper 1837

- Hall M. On the diseases and derangements of the nervous system. London, Bailiere 1841

- Hall M. New memoir on the nervous system. 1843

- Hall M. Essays on the theory of convulsive diseases. 1847

- Hall M. Synopsis of the diastaltic nervous system. 1850

- Hall M. Synopsis of cerebral and spinal seizures. 1851

- Hall M. On the threatenings of apoplexy and paralysis. 1851

- Hall M. Synopsis of apoplexy and epilepsy. 1852

- Hall M. The two-fold slavery of the United States; with a project of self-emancipation. 1854

- Hall M. On a new mode of effecting artificial respiration. Lancet 1856; 67(1696): 229 [Ready Method]

- Hall M. Asphyxia, its rationale and its remedy. Lancet 1856; 67(1702): 393-394

- Hall M. The ready method in asphyxia. Lancet 1856; 68(1730): 458-459

- Hall M. Abstract of an investigation into asphyxia: its nature, carbonic acid blood-poisoning, and its remedy, prone and postural respiration. London: Churchill. 1856

- Hall M. The danger of all attempts at artificial respiration, except in the prone position. Lancet; 1857; 69(1745): 134-135

- Hall M. Prone and postural respiration in drowning and other forms of apnoea or suspended respiration. London: Churchill. 1857

References

Biography

- Hall C. Memoirs of Marshall Hall. London: R. Bentley. 1861

- Green JH. Marshall Hall; 1790-1857: a biographical study. Med Hist. 1958 Apr;2(2):120-33.

- Manuel DE. Marshall Hall, F.R.S. (1790-1857); a conspectus of his life and work. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 1980 Dec;35(2):135-66.

- Biography: Marshall Hall. Lives of the Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians of London. Munk’s Roll: Volume IV, page 27

Eponymous terms

- Campbell FC. A claim of the priority in the discovery and naming of the excito-secretory system of nerves. 1857

- Jarcho S. Marshall Hall on crush injury and traumatic shock (1831). Am J Cardiol. 1967; 20(6): 853-6

- Manuel DE. Marshall Hall (1790-1857): Science and medicine in early Victorian society. Clio Med. 1996;37:x-xiii, 1-378.

- Pearce JM. Marshall Hall and “Romberg’s sign”. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005; 76(9): 1241.

- Baskett TF. Resuscitation greats: Marshall Hall and his ready method of resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003 Jun;57(3):227-30

Eponym

the person behind the name

MBChB, BMedSci in Global Health and Health Policy, University of Edinburgh. Currently working in the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Australia. Career focus is emergency medicine, with interests in humanitarian and pre-hospital care and treatment difficulties faced in resource-limited settings.

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |