Tonsillitis and the Bull

aka Tropical Travel Trouble 011

You are working in far North Queensland and encounter a 20 year old Indigenous man with tonsillitis on your ED short stay ward round.

He has been receiving IV penicillin and metronidazole overnight but is deteriorating and now cannot open his mouth beyond 1.5cm, and has a swollen neck (some might say ‘Bull neck’).

In addition, he now has “gurgly” breathing. He is taken to OT to be intubated by ENT and they report a grade 4 airway with “large grey tonsils and moist scales”.

Q1. What is your differential?

Answer and interpretation

- Viral pharyngitis

- EBV

- Group A Strep

- Oral Candidiasis

- Epiglottitis

- Diphtheria

- Ludwigs angina

Q2. What is the cause of this man’s tonsillitis?

Answer and interpretation

Diphtheria.

The word diphtheria comes from the Greek word for leather, which refers to the tough pharyngeal membrane that is the clinical hallmark of infection.

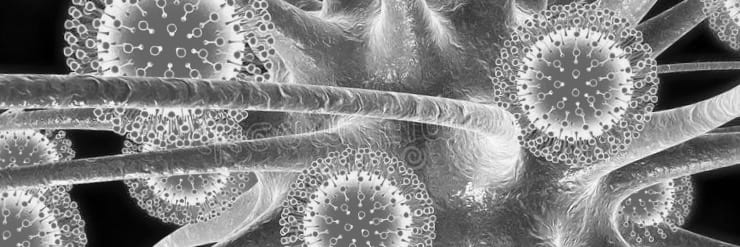

Here are a collection of images of the ‘grey pseudomembranous plaque’. The plaque occurs in the tosillopharyngeal region in 2/3rds of cases but can involve the laryngeal, nasal and tracheobronchial areas. Image 1 is in fact your barn door ‘regular tonsillitis’ for comparison.

Q3. What is diphtheria and how is spread?

Answer and interpretation

Diphtheria is caused by the gram-positive bacillus Corynebacterium diphtheriae or Corynebacterium ulcerans.

Diphtheria is spread by respiratory droplets or occasionally by direct contact with C. diphtheriae infected skin or an object/clothes. In some counties C.ulcerans moves from its cattle reservoir into the human population by the consumption of unpasteurised milk or close contact.

The incubation period of diphtheria is 2–5 days.

Q4. How would you confirm your clinical diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

Need to detect both the bacterium and the toxin. Asymptomatic pharyngeal carriage is relatively common therefore you could carry the toxin or the genes for the toxin but not have clinical disease.

Pharyngeal swab MC&S – Gram stain shows gram positive rods in a ‘Chinese character’ distribution for presumptive diagnosis. Swab the throat and under the membrane if possible. Label for diphtheria as this need to be grown on Loffler’s or Tindale’s media. For those of you who spend their time in the lab it is catalase positive, urease negative, cystinase positive, and pyrazinamidase negative.

Pharyngeal swab PCR – detect the DNA sequence encoding the A subunit of toxin. If negative this excludes diphtheria, if positive you also require a positive culture as the result only indicates the presence of the gene and not infectivity.

Other tests for toxins – there is a rapid enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for the detection of toxin and an Elek test which uses antitoxin impregnated filter paper laid over an agar culture of the organism (takes 24-48hrs to perform).

Q5. How does diphtheria cause harm?

Answer and interpretation

C. diphtheriae attaches to mucosal epithelial cells. Here an exotoxin is released by endosomes causing a local inflammatory reaction followed by tissue destruction and cell necrosis.

Inflammation mediated lymphatic and haemotologic spread means the endotoxin travels throughout the body leading to potential damage to the:

- Kidneys – renal failure and hypotension.

- Myocardium – In some studies 2/3rds of patients will have myocarditis (ST-T wave changes, QTc prolongation and/or first degree heart block – typically as the local respiratory symptoms improve or 7-14 days after the onset of symptoms). C. diphtheria has also been implicated in endocarditis and mycotic aneurysms.

- Nervous system – 75% of patients with severe disease will develop paralysis of the soft palate or posterior pharyngeal wall, cranial neuropathies and in some peripheral neuritis (weeks to months later) resulting in either mild weakness or complete paralysis.

The diphtheria endotoxin consists of 2 subunits – A and B.

- The B subunit binds to a receptor on the surface of the host cell and then proteolytically cleaves the membrane lipid layer allowing the A subunit to enter the cell.

- The A subunit then inhibits normal cell protein synthesis

Q6. Who is at risk of contracting Diphtheria?

Answer and interpretation

Diphtheria toxoid vaccination has been included in the childhood vaccination schedule since the 1920s in most developed countries. Therefore, those most at risk are the unimmunised.

Sporadic outbreaks are seen in mostly in disadvantaged groups who live in crowded conditions.

Adults and children under 5 are most at risk of dying from diphtheria with a mortality rate of up to 20%.

** Diphtheria global annual reported cases and DTP3 coverage 1980-2016

Q7. How does diphtheria present clinically?

Answer and interpretation

C. diphtheriae can infect any mucosal cell. There are two main forms of the disease (plus an asymptomatic carrier state):

1. Respiratory diphtheria (nasal, pharyngeal and laryngeal):

- Initially, patients present with URTI-like symptoms – pharyngitis, fever and cervical lymphadenopathy.

- As the disease progresses they develop a swollen neck (“bull neck” – a sign of malignant infection) and a thick grey “pseudomembrane” forms over the tonsils (of note this will bleed if scraped).

- The most common cause of death on day 3-5 of the illness is from airway obstruction or asphyxiation following pseudomembrane aspiration.

- Exotoxin mediated myocarditis occurs in up to 60% and is the second most common cause of death. The overall mortality rate from diphtheria is 5-10% even when adequately treated.

- In laryngeal diphtheria patients may only present with a cough and hoarseness as the larynx maybe the only site affected. Laryngoscopy will reveal a laryngeal pseudomembrane.

2. Cutaneous diphtheria

- Cutaneous diphtheria presents as a non-healing ulcer covered in a ‘dirty’ grey membrane. It occasionally progresses to respiratory diphtheria but this is rare due to a rapid response to treatment.

Q8. How do you treat diphtheria?

Answer and interpretation

It is important to treat with both antibiotics and diphtheria anti-toxin (DAT) before confirmatory diagnosis as delay in administering the anti-toxin is associated with significantly increased mortality.

If you suspect it, treat it immediately. There are commonly logistical delays on obtaining DAT, for example in Australia (it is only stocked in Brisbane), and there is limited worldwide supply due to ongoing outbreaks.

- Isolate your patient and use universal and droplet precautions.

- Secure airway pre-emptively.

- IV antibiotics:

- Erythromycin PO or IV (40 mg/kg/day; maximum 2 gm/day – adults 500mg Q6 hours) for 14 days OR

- Procaine penicillin G OD IM (300,000 U q12 hours <10kg and 600,000 U q12 hours >10kg), followed by oral penicillin V (250mg Q6 hours) for a total of 14 days.

- Patient is non-infectious 24 hours after commencing antibiotics.

- Repeat cultures at 24/48 hours and at 2 weeks after completion of treatment to prove eradication

Diphtheria antitoxin (DAT)

DAT is manufactured as snake antivenom (hyper immunised horses), so administration is as per snake antivenom. It neutralises the unbound exotoxin before it enters cells. Dose according to clinical severity (20,000 – 120,000 units):

- 20-40,000 for pharyngeal/laryngeal disease <48 hours

- 40-60,000 for nasopharyngeal disease

- 80-120,000 for >3 days of illness or diffuse neck swelling.

- 20-40,000 skin lesions only after discussion with a specialist.

Complications as seen with snake antivenom : anaphylaxis and serum sickness.

** Details on Diphtheria vaccination and Diphtheria antitoxin.

Q9. How do you prevent diphtheria?

Answer and interpretation

Mass vaccination is the best form of prevention. WHO recommends a 3-dose primary vaccination series with diphtheria toxoid, followed by a booster dose.

Children in Australia and New Zealand receive up to 6 doses of DTPa vaccine (diphtheria, tetanus and acellular pertussis toxoid).

In adults, opportunistic booster doses are given with the ADT or Boostrix vaccines more commonly used for their tetanus and pertussis properties. Serb-Surveillance studies in the UK show 50% of adults over the age of 30 are susceptible and increasing to 70% in the elderly.

Those individuals who are in close contact with a person with diphtheria should be swabbed and given a booster vaccine as well as prophylactic antibiotics for 2 weeks (penicillin or erythromycin).

Patients with diphtheria in hospital should be placed in respiratory droplet isolation and their bedding and clothes decontaminated.

Case Resolution

Case Outcome

While in ICU the patient developed myocarditis with a complete heart block requiring a temporary pacing wire. He received DAT on day 3 of illness. Unfortunately, despite aggressive supportive therapy he developed multi-organ failure and passed away on day 16 of illness.

References

- Beeching N, Gill G. Lecture Notes – Tropical Medicine. 7e. Wiley Blackwell

- Eddleston, Davidson, Brent, Wilkinson. Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine. OMH 4e

- Farrar J et al. Manson’s Tropical Diseases 23e. Elsevier

- Magill AJ, Ryan ET, Solomon T, Hill DR. Hunter’s Tropical Medicine and Emerging Infectious Disease. 9e. Elsevier

- The Green Book – Diphtheria

CLINICAL CASES

Tropical Travel Trouble

Peer Reviewers

• Dr Jennifer Ho: ID physician QLD, Australia

• Dr Mark Little: ED physician QLD, Australia

MBChB, MEmergHlth, FACEM. Kiwi emergency physician working in tropical Far North Queensland. Work interests include little people and making things happen faster and better. Outside work I'm a lifetime wonderer, devoted festival attendee, recurrent toddler wrangler and occasional body builder