Renal colic

Renal colic (or nephrolithiasis) is an extremely common presenting problem to the Emergency Department. The immediate priority will be pain relief.

Introduction

~90% of stones pass spontaneously within 1 month. Stones >5 mm are less likely to pass without intervention. Most patients managed in ED; admission criteria include:

- Fever/sepsis (urological emergency)

- Intractable pain

- Severe hydronephrosis

- Impaired renal function

- Single functioning kidney

- Bilateral ureteric stones

- Transplanted kidney

History

- Long historical context: ancient surgical records of stone management.

- Modern imaging: CT-KUB replaced IVP.

- Treatment: ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy preferred over extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL).

Epidemiology

- 50% have single episode; 50% recur in 5 years.

- Common in ages 20-50; alternative diagnoses in young/elderly.

Pathophysiology

- Contributing factors: dehydration, genetics.

- Stone types:

- Calcium-based (75%). States of hypercalcaemia (from any cause) may predispose to calcium stones [Calcium oxalate, Calcium phosphate, Calcium oxalate/ phosphate mix]

- Uric acid (8%) – associated with a urinary pH of less than 5.5, high dietary purine intake or malignancy (i.e., rapid cell turnover).

- Struvite (15%) – (magnesium ammonium phosphate) – associated with chronic urinary tract infection with gram-negative bacilli. Usual organisms include Proteus, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella species.

- Cystine (2%) – metabolic defect resulting in failure of renal tubular reabsorption of cystine, ornithine, lysine, and arginine.

- Xanthine (rare) – inborn defect of the enzyme xanthine oxidase

- Common points of obstruction:

- PUJ – Pelviureteric junction

- Pelvic brim

- VUJ – Vesicoureteric junction

Complications

- Infection – urological emergency

- Severe hydronephrosis (risk of atrophy, ureteric rupture)

Clinical Assessment

- Symptoms: severe, colicky loin to groin pain, N/V

- Pain location varies with stone position

- Pain confined to the RIF/ LIF may indicate a stone in the region of the VUJ

- Bladder stone may result in suprapubic pain or a sense of urgency/ frequency

- Assess for coagulopathy (e.g. warfarin/DOAC)

- Key exam points: vitals, flank/abdominal pain, testicular exam

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical diagnosis of renal colic is usually straight forward, although without radiological imaging can never be definitive. Not all presentations of renal colic are “classical” and important differential diagnoses are legion and the risk profile for various pathologies needs to be carefully assessed in each patient.

- AAA

- Lung pathology (e.g. PE, pneumonia)

- Retroperitoneal hematoma

- Renal malignancy

- PUJ obstruction

- Testicular torsion

- GIT (e.g. appendicitis, diverticulitis, bowel obstruction)

- Spinal pathology; disc disease/sciatica/malignancy

- Gynecological: ectopic pregnancy, ovarian torsion

Investigations

- Bloods: FBE, CRP, U&E, glucose, LFT/lipase, beta-HCG (if needed)

- Metabolic screen (Ca, PO4, uric acid)

- FWT: hematuria often present but not definitive

- Stone analysis: if passed

- KUB X-ray: done if CT-positive for stone to guide follow-up. Note that 100% of stones are seen on CT, whilst only 85% of stones are seen on plain x-ray. Whether a stone is seen on plain x-ray largely depends on its composition.

- CT-KUB: gold standard for diagnosis. It can accurately determine the size of the stone – an essential parameter for planning both disposition and management. CT may also distinguish complicating pyelonephritis and uroma

- Ultrasound: detects hydronephrosis, less sensitive for stones

- MRI: alternative for pregnancy

Management

- Analgesia

- NSAIDs preferred (ibuprofen, ketorolac, indomethacin)

- Opioids (morphine or fentanyl IV)

- IV Fluids

- For dehydration or prolonged NBM

- Tamsulosin

- May assist passage of distal stones 5-10 mm

- Intervention Options

- ESWL: least invasive, limited efficacy

- Ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy: most common, high efficacy

- Percutaneous nephrolithotomy: for >2 cm/staghorn calculi

- Open surgery: rarely used

- Nephrostomy: urgent drainage in obstruction + sepsis

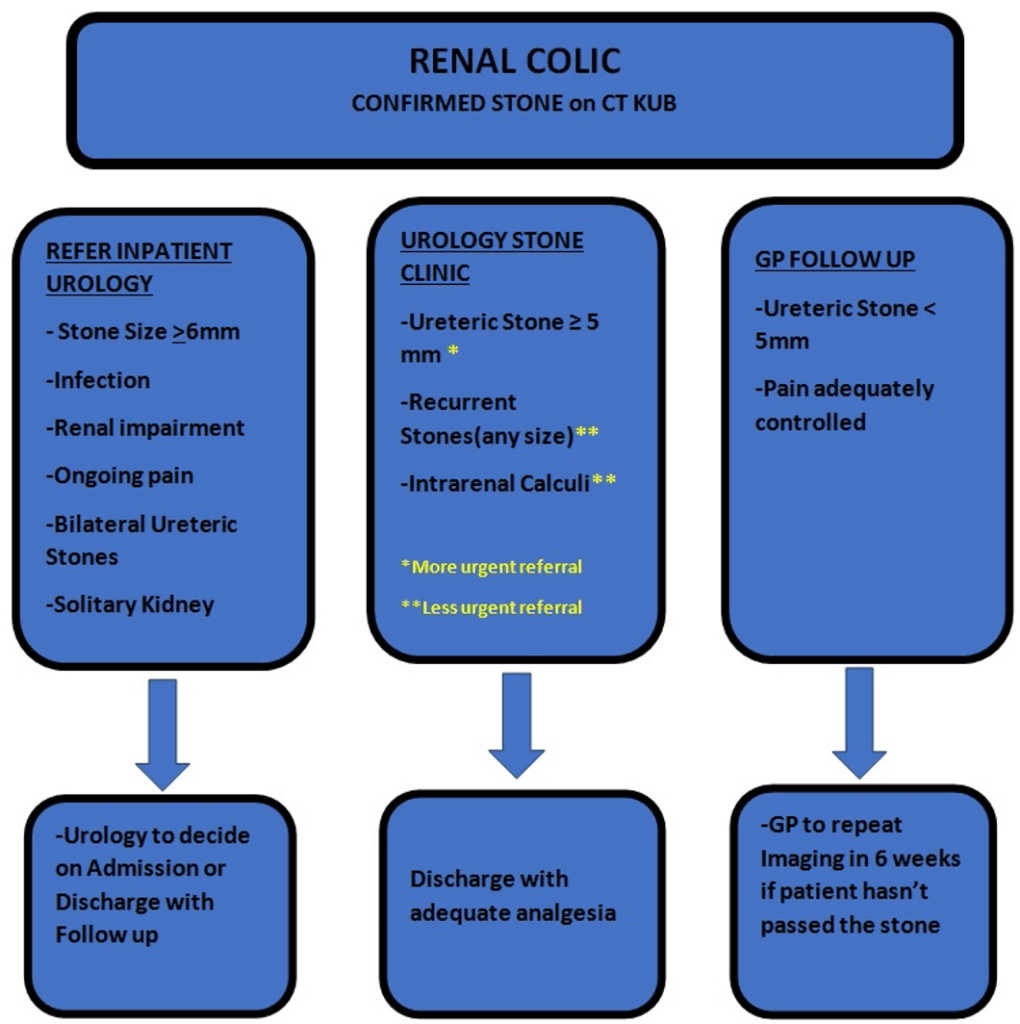

Disposition

- ED discharge if:

- Symptoms controlled

- No complicating factors

- Small stone (<5 mm)

- Admission if:

- Fever

- Intractable pain

- Deteriorating renal function.

- Severe hydronephrosis

- Single kidney or bilateral obstruction

- Patients with a transplanted kidney

- Stone >5 mm (especially proximal) – have high rates of re-presentation

Follow-Up

- Urology outpatient referral:

- Ureteric stone ≥ 5 mm

- Recurrent stones

- Intrarenal calculi

- GP follow-up:

- Single episode, stone <5 mm, uncomplicated

Appendix 1:

Patients with intractable pain:

Intractable pain may be due to a large stone (> 5 mm), which will have difficulty in passing spontaneously or severe hydronephrosis or even a “uroma”(ruptured caylaceal system). In general terms:

| Stone Size | Likely outcome |

| ≤ 4 mm | 90 % will pass within a month |

| 5- 7 mm | 50 % will pass within a month |

| ≥ 7 mm | 5 % will pass within a month |

The overall passage rates for a stone within the ureter are:

| Position within the Ureter | Overall likelihood of passage |

| Proximal ureteric stones | 25% |

| Mid ureteric stones | 45% |

| Distal ureteric stones | 75% |

Appendix 2:

Appendix 3:

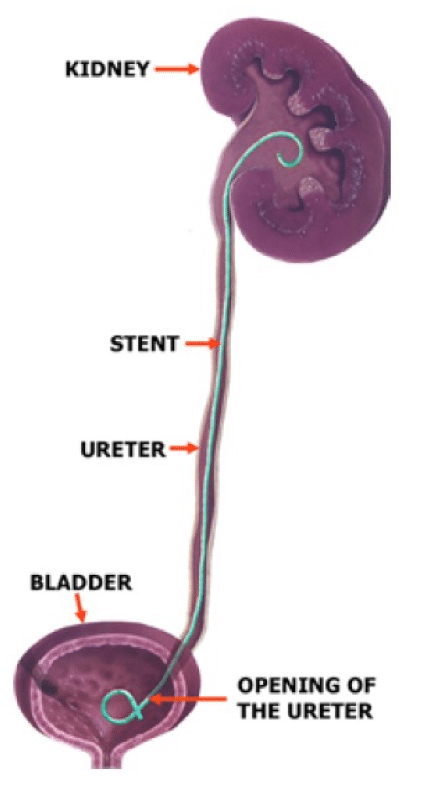

The Double J Stent:

The double J stent is a thin, hollow stent that is often placed inside the ureter during surgery to ensure drainage of urine from the kidney into the bladder. J shaped curls are present at both ends to hold the tube in place and prevent migration, hence the description “double J stent”.

They allow the kidney(s) to drain urine by temporarily relieving any blockage, or to assist the kidney(s) in draining stone fragments freely into the bladder if definitive kidney stone surgery is carried out.

Stents are used in temporary situations and must eventually be removed from the body, within 6 months – but most are removed well before this

References

FOAMed

- Cadogan M. Dietl’s Crisis. LITFL

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: renal stones. LITFL

- Yousif F. POCUS Made Easy: Renal LITFL

- Cunningham K. Abdominal Imaging Cases 017. LITFL

- Rippey J. Ultrasound Case 103 Fire and Brimstone. LITFL

- Rippy J, Aldawood A. Ultrasound Case 106. LITFL

Publications

- Holdgate A, Pollock T. Systematic review of the relative efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids in the treatment of acute renal colic. BMJ. 2004 Jun 12;328(7453):1401

- Holdgate A, Oh CM. Is there a role for antimuscarinics in renal colic? A randomized controlled trial. J Urol. 2005 Aug;174(2):572-5; discussion 575.

- Furyk JS, Chu K, Banks C, Greenslade J, Keijzers G, Thom O, Torpie T, Dux C, Narula R. Distal Ureteric Stones and Tamsulosin: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomized, Multicenter Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2016 Jan;67(1):86-95.e2

Fellowship Notes

Physician in training. German translator and lover of medical history.

Educator, magister, munus exemplar, dicata in agro subitis medicina et discrimine cura | FFS |