Abdominal CT: renal stones

Detecting renal stones

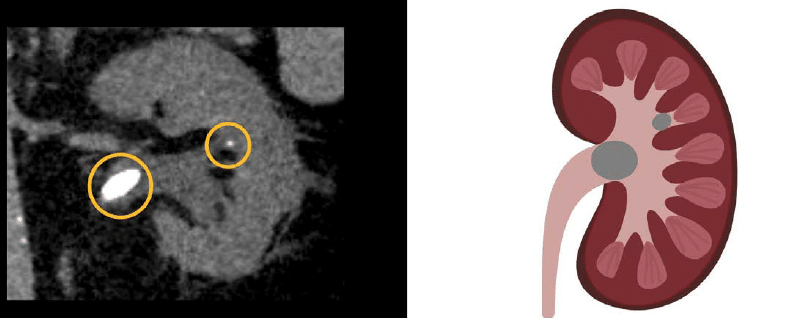

Renal stones are hard deposits that form in the kidney. They can move down the urinary tract, causing obstruction and pain as well as blood in the urine. Most stones are calcified and visible on CT as bright dots. They can range from a small bright dot to a large stone…

Concern about kidney stones is a common reason to obtain CT in the emergency department. Patients often present with flank pain radiating to the groin and haematuria.

When reviewing CT images for these patients, it is important to look for stones along the entire genitourinary tract as they can result in varied degrees of upstream obstruction and inflammation.

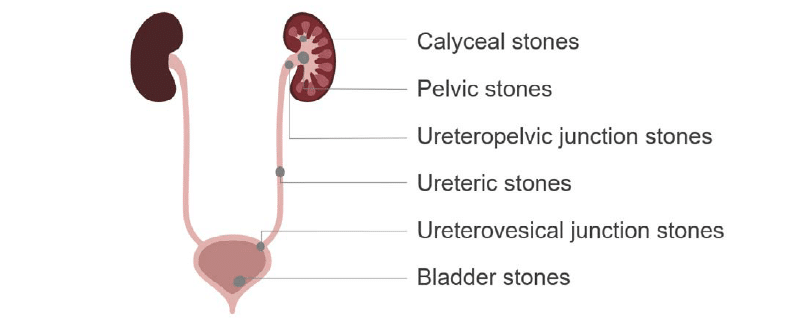

There are six key locations where kidney stones can occur:

- Calyceal stones. These are confined to the kidney, are often small, and usually do not cause obstruction until they migrate.

- Pelvic stones. These can cause partial obstruction or inflammation of the kidney pelvis.

- Ureteropelvic junction stones. These become lodged in the proximal ureter as they leave the tapering renal pelvis.

- Ureteric stones. These occur along the course of the ureter and are often symptomatic.

- Ureterovesical junction stones. These are found where the ureter joins the bladder.

- Stones within the bladder. These can be due to a passed stone or one that formed in the bladder due to urinary stasis.

Ultrasound can be used to screen for dilation and obstruction of the kidney, also known as hydronephrosis. However, it is not very good at seeing or accurately measuring stones in the kidney, and it cannot provide an image for most of the ureter.

For this reason, CT is the best examination tool to evaluate the entire urogenital tract. Most institutions have a specialized CT study called a CT flank pain study or renal stone study. This study can be used to look for stones without the use of contrast and at a lower radiation dose than a typical CT.

The flank pain study is very similar to a non-contrast CT except the patient is usually asked to drink water rather than bright oral contrast. Drinking water can help to distend the urinary system, making it easier to view.

Key findings

There are three key findings to indicate the presence of stones and possible obstruction in a CT flank pain study:

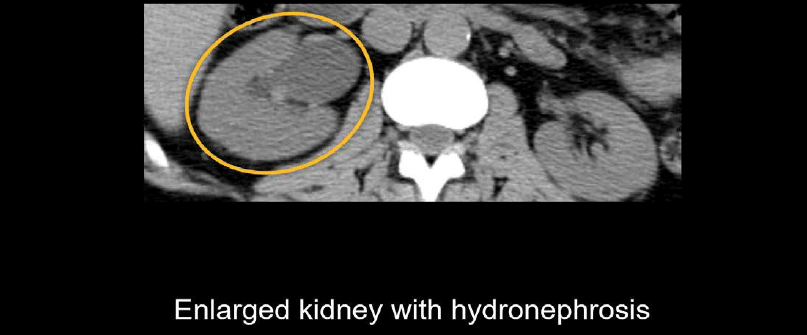

- Asymmetric kidney size and hydronephrosis

- Dilation of the proximal ureter

- Calcified renal stones of various sizes and locations in the kidney

Asymmetric kidney size and hydronephrosis. These can indicate obstruction and edema of the affected kidney.

Dilation of the proximal ureter. Dilation can lead you to the site of a more distal obstruction. Notice below how the dilated right ureter compares to the normal left ureter.

Calcified renal stones of various sizes and locations in the kidney In the example below, there is a larger stone in the pelvis and a tiny calyceal stone in the mid kidney.

Contrast-enhanced study

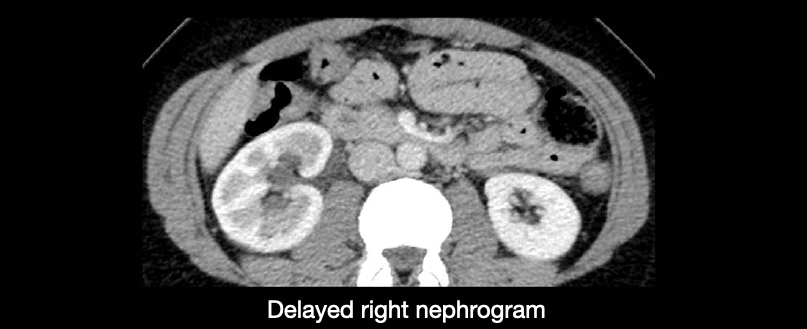

You can still identify renal stones on a contrast-enhanced study, of course. But keep in mind that when a kidney is obstructed, it will enhance more slowly than the non-obstructed kidney due to increased pressures.

A contrast-enhanced study can help you identify the problem when you compare the kidneys side by side. You might also see increased enhancement of the ureter related to inflammation caused by the passing stone.

Example 1

The right kidney is swollen and enhancing less than the left, and you can still see the inner medulla. The left kidney is normal-sized and enhances more uniformly throughout. Thus, there is a delayed right nephrogram, which indicates obstruction somewhere along the course of the right ureter.

Example 2

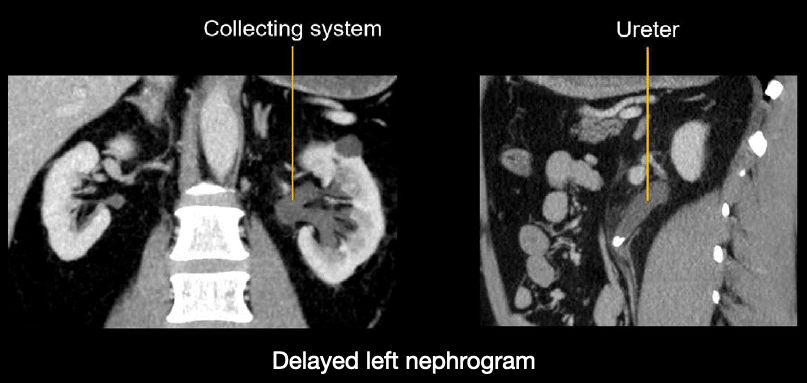

The left kidney enhancement is delayed due to a proximal ureteric stone. These images nicely illustrate the dilated collecting system and ureter leading toward the obstructive stone.

Reading a flank pain CT

Renal stones can be diagnosed using a special non-contrast scan known as a flank pain CT. here are two more examples to help practice diagnosing renal stones

Case 1

Scroll through these PACS viewer images

- Start by choosing to view the axial and coronal images side-by-side so you can find your landmarks.

- As you make your way down, scroll through the kidneys looking for the key findings of asymmetric enlargement, hydronephrosis, and calcified stones.

- Stones form near the tip of the renal pyramids, so focus your review there.

- Notice that the right kidney looks okay, but the left kidney is enlarged and has surrounding stranding, indicating edema.

- There is also dilation of the collecting system and calyces, which you can confirm by comparing the right and left sides on the coronal images.

- You’ll notice a tiny stone near the calyx that is not causing obstruction.

- You’ll also find a large stone at the junction of the renal pelvis and proximal ureter.

- The diagnosis here is a ureteropelvic junction stone causing mild hydronephrosis.

- Practice measuring the size of the stone, as this measurement will help guide treatment.

Case 2

Scroll through these PACS viewer images of a a patient presenting with flank pain and blood in the urine

- Starting with the axial images, notice the right kidney is asymmetrically enlarged

- Notice also that it has dilated, urine-filled calyces, which is referred to as hydronephrosis.

- Following the dilated right ureter down to the urinary bladder, you will find a small, rounded calcification at the ureterovesical junction.

- The left ureter and kidney are free from stones or obstruction.

- The diagnosis in this case is a right ureterovesical junction stone causing mild upstream dilation of the ureter and kidney, collectively referred to as hydroureteronephrosis.

This is an edited excerpt from the Medmastery course Abdominal CT Pathologies by Michael P. Hartung, MD. Acknowledgement and attribution to Medmastery for providing course transcripts

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: Common Pathologies. Medmastery

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: Essentials. Medmastery

- Hartung MP. Abdomen CT: Trauma. Medmastery

References

- Top 100 CT scan quiz. LITFL

Radiology Library: Acute abdomen. Solid organ and Vascular pathology

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: acute interstitial pancreatitis

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: acute necrotizing pancreatitis

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: renal stones and the flank pain CT

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: renal infections

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: cholecystitis

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: intestinal ischaemia

- Hartung MP. Abdominal CT: rupturing abdominal aortic aneurysm

Abdominal CT interpretation

Assistant Professor of Abdominal Imaging and Intervention at the University of Wisconsin Madison School of Medicine and Public Health. Interests include resident and medical student education, incorporating the latest technology for teaching radiology. I am also active as a volunteer teleradiologist for hospitals in Peru and Kenya. | Medmastery | Radiopaedia | Website | Twitter | LinkedIn | Scopus

MBChB (hons), BMedSci - University of Edinburgh. Living the good life in emergency medicine down under. Interested in medical imaging and physiology. Love hiking, cycling and the great outdoors.