A Touch Extreme

Sports medicine at the Touch World Cup in Malaysia

The quadrennial 9th edition of the Touch World Cup took place during May, 2019 in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Traveling as the Australian team doctor, thorough medical preparation was critical when the tournament posed significant challenges playing in extremely hot conditions, dealing with outbreaks of traveler’s diarrhoea and the logistics of caring for a touring party of more than 220 people in a foreign country.

Touch football is a variation of rugby league played as unisex or mixed teams with 6 players on the field per side. Games are played over 2 x 20 minute halves at a rapid pace requiring high levels of speed, endurance and skill. Approximately 2,400 athletes from 26 countries were represented at the 6-day tournament in Malaysia. Australia and New Zealand were the teams to beat, with both nations competing in most of the 11 category finals and Australia emerging victorious in 81. Kuala Lumpur, the capital and largest city of Malaysia, is notoriously hot and humid, which became a significant issue as large numbers of players suffered exertional heat illness.

Exertional heat illness is a continuum of heat-related medical problems experienced during exercise2, with heat cramps and heat rash at the mild end, up to the severe end with heat-stroke having potentially fatal consequences. Some risk factors include exercise intensity, recent illness, lack of acclimatisation and high ambient weather conditions2; all of which were prevalent issues for many of the touring group. Of most concern were the ambient conditions, which on one day reached a high of 51.9oC on the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)3. The most important factor dealing with heat-related illness is early recognition of concerning signs and symptoms, such as altered GCS and a core body temperature >40oC 2, and being prepared to rapidly cool the player.

The British Journal of Sports Medicine released a consensus recommendation in 2015 on training and competing in the heat4 which proposes 4 strategies to optimise performance in hot conditions; namely heat acclimatisation, hydration, cooling and recommendations for event organisers. Heat acclimatisation is championed as the most important intervention and would ideally involve 1-2 weeks of being exposed to exercise in the heat before commencement of competition. Hydration recommendations include monitoring morning body mass for fluid losses, drinking 6mL of fluid per kg of body mass 2-3 hours before exercise, minimising fluid loss during exercise and adequately rehydrating afterwards with fluids containing sodium, carbohydrates and protein.

Cooling strategies include external means (cold-water immersion, applying iced garments/ towels, fanning) and internal means (ingestion of cold fluids or ice-slurry) with a mixture of both being more effective than any strategy in isolation. Recommendations for event organisers include monitoring the WBGT with appropriate heat policies, scheduling play around the weather conditions and paying particular attention to ‘at risk’ populations, such as those that are unacclimatised or who have a recent or current illness. Thankfully for our Australian party, most people already lived in a hot climate and were somewhat acclimatised.

We were vigilant with hydration, fluid loss monitoring and we had access to all of the cooling strategies recommended. The event organisers also took heed of the recommendations and included more breaks in play or cancelled play completely if extreme heat conditions were encountered (play was even postponed on finals day due to lightning strike). Despite all of these measures, I still had to manage a handful of players at high risk of heatstroke requiring rapid cooling via cold water immersion, rehydration with intravenous fluids and transfer to a medical facility for further monitoring and treatment without serious consequence.

Photo: Glen Eaton/Aisle 5 Photography

A significant risk factor for heat illness is recent or current illness. This was a significant issue for many participants at the tournament who experienced ‘traveler’s diarrhoea (TD)’. Mild (acute) TD is defined as “diarrhoea that is tolerable, is not distressing, and does not interfere with planned activities” while severe (acute) TD is “diarrhoea that is incapacitating or completely prevents planned activities”5.

TD is the most common infectious illness encountered by travelling sports teams6 and risk factors include location (Malaysia is high risk) and a lack of caution in food and beverage selection7 with poor hygiene. In Southeast Asia, the most common pathogens responsible are Campylobacter, Escherichia coli, Salmonella and Giardia7. As with managing exertional heat illness, the key to TD is preparation and prevention. Dietary advice including “boil it, cook it, peel it, or forget it”7, consuming only bottled beverages and being vigilant with hand hygiene can significantly reduce risk.

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be reserved for travelers at severe risk of complication from diarrhoea5, but treatment for established TD with a course of Azithromycin (1000mg single dose or 500mg for 3 days) is first-line treatment in Southeast Asia to help reduce the duration of moderate to severe TD7. In most instances though, supportive therapy will suffice, including oral rehydration solution, anti-spasmodics for abdominal cramps and an antimotility agent. Loperamide can be particularly useful for players who can’t afford to have frequent bowel motions during competition.

Photo: Glen Eaton/Aisle 5 Photography

The final critical piece of the medical puzzle traveling with a 220-strong contingent was preparing the players and staff themselves. Before leaving Australia, everybody had to submit a medical history of pre-existing conditions that I reviewed and addressed. In some instances this required follow-up, but it was mostly being aware of potentially life-threatening conditions (e.g. anaphylaxis, severe asthma), ensuring everybody had enough of their prescription medications and that everyone had comprehensive travel insurance.

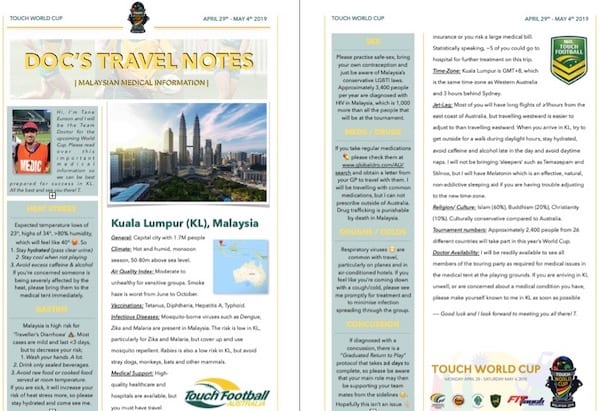

I also compiled ‘travel notes’ educating the touring group on likely health issues we would encounter at the tournament and relevant medical advice (see figure below). Once we prepared our players, it was critical to also know what medical facilities and resources were available at the tournament.

My greatest resource was a fantastic group of Australian physiotherapists, trainers and local massage therapists to shoulder the large number of musculoskeletal issues. For more critical medical concerns, the tournament venue was equipped with 3 temporary medical stations that were staffed by Malaysian emergency and sports medicine doctors with the ability to perform basic bedside imaging and monitoring, or they could rapidly transfer players to a nearby tertiary hospital if required. Their help was invaluable at times when I had players require more intensive monitoring and management for heat illness and investigations for deep vein thromboses and pneumothorax. Without the luxury of having their expertise on hand, it would have been imperative to know where the nearest emergency centre was, how to get there and how to facilitate timely investigations if needed.

The Touch World Cup in Malaysia was a great success both on and off the field for Australia. The main lesson I took as the traveling team doctor was that preparation is vital. By knowing who and what to expect at your destination, the medical team can be best prepared for whatever comes their way, even if the situation becomes a touch extreme.

References

- Australia dominate touch world cup. Federation of International Touch. 2019

- Springer B. Exertional Heat Illness. Cambridge University Press: 2016; p 390-407.

- Kenney WL. Physiology of sport and exercise, 5e. Human Kinetics. 2012.

- Racinais S et al. Consensus Recommendations on Training and Competing in the Heat. Sports Med. 2015 Jul;45(7):925-38

- Riddle MS et al. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: a graded expert panel report. J Travel Med. 2017 Apr 1;24(suppl_1):S57-S74.

- Brukner P, Khan K. Brukner & Khan’s Clinical Sports Medicine, 4e. McGraw-Hill Education. 2011.

- Steffen R, Hill DR, DuPont HL. Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015 Jan 6;313(1):71-80

Māori doctor passionate about sport & exercise medicine. #FOAMed evangelist | @taneeunson | LinkedIn

Half-wimps, the lot of them.

If only the typically solo remote workers and farm workers had a team of physio’s and specialists around them each day as they cope with the heat and dust and flies and run-down old machinery, as they try to feed and clothe the nation.

Anyway, hopefully all the touch footy players are taught that HS is accumulative, and after the first serious taste of it they will never be the same sports person again, and that their deep life force is forever damaged. It may be un-noticable the first time, but the fatigue has begun, as silently as kidney disease.