Angelo Mosso

Angelo Mosso (1846 – 1910) was an Italian physiologist, archaeologist, politician, mountain climber and teacher.

Having been into poverty and made to work in his father’s carpenter shop, Mosso’s modest upbringing shaped him to hold strong values on education and equality, and his hard work and brilliant results in secondary schooling allowed him to pursue the study of medicine. Mosso would then go on to establish himself as one of the most brilliant physiologists of the time, studying under the likes of Maurizio Schiff and Carl Ludwig, and being at the forefront of human circulation and muscular physiology.

Becoming the chair of physiology at the University of Turin at the age of 33, Mosso’s 25-year tenure of the post would see the department become known as a ‘physiological mecca’ due to the myriad of high-profile physiologists whom he trained and collaborated with, amongst them being Vittorio Aducco, Amedeo Herlitzka, David Ferrier, and Harvey Cushing. During that time, Mosso would also combine his love of mountain climbing and physiology to successfully launch the idea of establishing a research station in the Alps.

A man of many interests, Mosso gave lectures on various topics, ranging from mountain climbing to wine diffusing, and had stints in politics and archaeology during the later years of his life, becoming a senator of Italy and making a few prominent archaeological discoveries. Despite his astronomic success, Mosso always remained true to his frugal roots, even going as far as to write a book on the modern life of Italians dedicated to his daughter, Mimi Mosso, so that she could ‘learn about her country and how to love the poor.’

Mosso is best known for his work regarding neuroimaging and muscular fatigue. He is eponymous with the Mosso Method and Mosso Balance and is attributed to the discovery of Bozzolo’s sign.

Biography

- Born 30 May 1846 in Turin, Italy.

- July 1870 – Graduated Doctor of Medicine from the University of Turin magna cum laude.

- 1870 – 1871 – Posted at Florence, Naples, Salerno, and Messina as a battalion physician.

- 1871 – 1874 – Researcher under Maurizio Schiff in Florenze, Italy, where he met Giulio Ceradini who introduced him to the graphical method.

- 1874 – 1875 – Researcher under Carl Ludwig and student of the graphical method to Leopold Kronecker in Leipzig, Germany.

- 1875 – Went to Paris to work with Claude Bernard and Étienne-Jules Marey; returned to Turin and appointed Professor of Pharmacology at the University of Turin.

- 1879 – 1904 – Chair of Physiology at the University of Turin

- 1879 – Awarded the Royal Prize by the Accademia de Lincei for his work on the circulation of blood in the brain.

- December 1881 – Awarded National Fellow of the Accademia dei Lincei.

- 1882 – Founded Les Archives Italiennes de Biologie with zoologist Carlo Emery.

- 1901 – Presided over the 5th International Congress of Physiologists held in Turin.

- 1904 – Senator of the Kingdom of Italy.

- 1905 – Invited to speak at the Olympic Games held in Rome, Italy.

- Died 24 November 1910, possibly due to complications relating to diabetes.

Key Medical Contributions

The Mosso Method and Mosso Balance (1880, 1882)

Sulla circolazione del sangue nel cervello dell’uomo. 1880

During his European tour, Mosso learned to utilize graphical methods to investigate the dynamics of physiological phenomena under the tutelage of Étienne-Jules Marey; an expert on graphical methods and photographic techniques who had pioneered cinematography. Upon his return to Turin, he applied the graphical method to measure numerous physiological processes, including the circulation in the human brain.

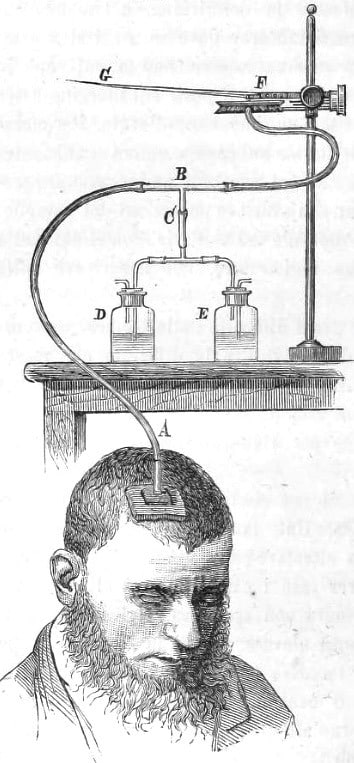

Mosso began by measuring the pulsations of the human cortex in patients with skull defects following neurosurgical procedures by means of a special plethysmograph he developed for this purpose. By converting brain pulsations into plethysmographic waves, Mosso was able to quantify the magnitude and changes in volume and from this, he inferred that an increase in mental activity resulted in increased blood flow to the brain. Mosso documented these findings in his paper Sulla circolazione del sangue nel cervello dell’uomo, and this technique of measurement was later aptly named the Mosso Method.

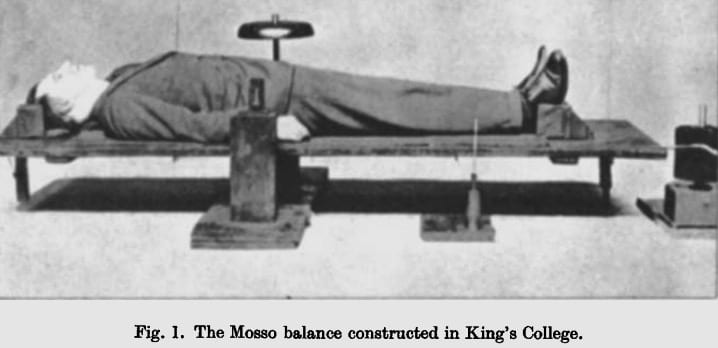

The Mosso method, however, was only applicable to subjects with skull breaches and could not be used to assess blood flow variations in healthy subjects. Mosso overcame this limitation by developing an apparatus he named the ‘human circulation balance’ (Mosso’s balance). The apparatus consisted of a wooden table lying on a fulcrum, with the subject lying supine and very still. The table would tilt with the slightest increase in weight, and it was this sensitivity that allowed the device to measure the subtle changes in weight that resulted from an increased blood flow to the brain during mental stimulation. Careful positioning and instructions, alongside a variety of weights and counterweights, were implemented to offset any artifactual changes, such as that arising from changes in blood flow due to respiration.

Mosso was awarded the Royal Prize by the Accademia de Lincei for his work on the circulation of blood in the brain in 1879; one year before his first work on the topic was officially published. His inventions on measuring changes in blood flow of the brain are regarded as the first-ever neuroimaging technique and a forerunner of the more refined techniques of FMRI and PET.

Bozzolo sign (1887)

Visible pulsation of the arteries within the nasal mucosa. Initially described with thoracic aortic aneurysm, later associated with aortic regurgitation

Bozzolo attributed his sign to the previous work and studies of Giulio Ceradini (1844 – 1894) and Angelo Mosso (1846 – 1910)

Muscular Fatigue (1891)

La Fatica, a book comprising of multiple studies undertaken by Mosso on the subject of muscle fatigue, is widely regarded as one of his best works. The book not only aimed to disseminate his scientific findings, but also conveyed strong views on prominent cultural and sociopolitical themes and ideas, and resultingly the book influenced doctors, politicians, sociologists, entrepreneurs, scholars, and revolutionaries of the time.

To achieve his goal, Mosso first analysed the fatigue seen in birds who flew great distances, analogizing birdwings to the human arm, and the origin of muscle strength, starting with the notes of Helmholtz on the relationships between heat, work, and energy transformations. He then developed a device known as an ergograph that allowed him to measure muscle contractions in human subjects, and utilized this to study fatigue under a range of different variables.

From his analyses, Mosso was able to characterize muscle fatigue and associate its occurrence with mental or muscular influences, demonstrate that exercise would increase muscular strength and endurance whilst prolonging the occurrence of fatigue, and describe the phenomenon of contracture, and formulated a set of laws regarding exhaustion.

Mosso’s work on fatigue was commemorated during the 2005 International Congress of Physiological Sciences; over 100 years after they were published.

Mosso’s Laws of Exhaustion as described in La Fatica

- Il consumo del nostro corpo non cresce in proporzione del lavoro. Se faccio un lavoro eguale ad uno non si può dire, avrò uno di fatica; e per due, o per tre di lavoro successivo, avrò due o tre di fatica in più.

- Esaminando ciò che succede nella fatica, due serie di fenomeni richiamano la nostra attenzione. La prima è la diminuzione della forza muscolare. La seconda è la fatica come sensazione interna. Abbiamo cioè un fatto tisico che possiamo misurare e paragonare, ed uno psichico che sfugge allemisure ed ai raffronti.

- I bambini poveri moiono in maggior numero che non i bambini delle classi agiate, o, crescendo, vengono su meno prosperosi, perchè il vitto loro è insufficiente, o perchè risentono gli effetti della fatica che sopportarono le loro madri durante la gravidanza.

- L’esaurimento più grave delle torze e lo strapazzo non succede nella campagna, ma nelle miniere dello solfo. Pasquale Villari, il celebre storico, l’autore della Storia di Girolamo Savonarola e di quella di Niccolò Machiavelli, scrisse già un libro sulla questione sociale dell’Italia meridionale.

- Se ci voltiamo indietro nella storia degli ultimi secoli, vediamo che tutti i popoli sono dominati da unapreoccupazione costante, quella di rendere più intenso il lavoro del cervello e delle braccia. La società moderna si affatica con moto sempre più rapido, con strumenti sempre meglio adatti a moltiplicare e rendere più fecondo il lavoro dei muscoli e dell’intelligenza. L’allargamento prodigioso delle industrie, la velocità accresciuta delle macchine ci incalzano, e la fretta ci spingerà sempre più, e crescerà fino all’estremo, fino là dove la legge dell’ esaurimento metterà un limite insuperabile all’ingordigia del guadagno.

- La macchina non riconosce altro limite nella sua velocità che la debolezza dell’uomo che deve darle aiuto… lo stesso Marx che scrisse certo il libro migliore della letteratura socialistica, non dà nell’opera sua il Capitale prove serie ed inoppugnabili, dell’esaurimento che le macchine producono nell’operaio.

Mosso: La Fatica, 1891

- The consumption of our body does not grow in proportion to the work. If I do a job equal to one unit of effort, it cannot be said that if the work doubled or tripled, I will use two or three times more effort.

- By examining fatigue, two sets of phenomena call our attention. The first is the decrease in muscle strength. The second is fatigue as an internal sensation. In other words, we have a physical fact that we can measure and compare, and a psychic that escapes measurement and comparison

- Poor children die in greater numbers than children of the upper classes, or, growing up, they are less prosperous, because their food is insufficient, or because they are affected by the effects of the fatigue that their mothers endured during pregnancy.

- The most severe exhaustion of the [body] does not happen in the countryside, but in the sulphur mines. Pasquale Villari, the famous historian, the author of the History of Girolamo Savonarola and that of Niccolò Machiavelli, already wrote a book addressing the social questions of Southern Italy.

- If we turn back in the history of the last centuries, we see that all peoples are dominated by a constant concern, that of making the work of the brain and arms more intense. Modern society is getting tired with faster and faster motion, with better and better tools multiply and make the work of muscles and intelligence more fruitful. The prodigious enlargement of the industries, the increased speed of the machines press us, and the haste will always push us more, and will grow to the extreme, up to where the law of exhaustion will put an unsurpassed limit on the greed of earnings.

- The machine recognizes no other limit in its speed than the weakness of the man who must help her … Marx himself, who certainly wrote the best book of socialist literature, fails to convey in his works the serious and incontrovertible proof of the exhaustion that machines produce in the worker.

Mosso: La Fatica, 1891

Experimental Psychology

In 1884, Mosso published a text titled La Paura discussing physiological explanations for the psychological reactions seen in fear. This drew the attention of psychologists such as Agostino Gemelli and Mario Ponzo, whom were attracted to his Institute of Physiology to study with him, and the hypotheses Mosso construed from his work were confirmed by Cesare Lombroso with his studies on the anthropology of criminals.

Mosso was also successful in having a resolution passed during his 1901 presidency of the Fifth International Congress of Physiologists in Turin, which saw efforts be made for the teaching and research of experimental psychology in universities where the subject did not yet exist.

Other Contributions

Mosso’s love of altitude science prompted him to launch the idea of a scientific station up in the Alps in 1901 during the 5th International Congress of Physiologists held in Turin. His idea gained traction and support from the scientific community, the national government and even Queen Margherita of Savoy, and in 1903 the newly opened Alpine Station at Col d’Olen was named after Mosso, by unanimous vote of the physiologists meeting at the 7th International Congress of Physiology in Heidelberg.

In his later years (1907-1910), Mosso was also an accomplished archaeologist, having participated in excavations in Sicily, Lazio (Tarquinia), and Puglia (Molfetta, Terlizzi, Manfredonia, and Bisceglie), and discovering 49 Neolithic tombs in the sought after metropolis and the Dolmen of Bisceglie in the Province of Bari in 1908.

Major Publications

- Mosso A. Introduzione ad una serie di esperienza sui movimenti del cervello nell’uomo. Archivio per le scienze mediche 1876; 1: 206-244

- Giacomini C, Mosso A. Esperienza sui movimenti del cervello nell’uomo. Archivio per le scienze mediche 1876; 1: 245-278

- Mosso A. Sul polso negativo e sui rapporti della respirazione addominale et toracica nell’uomo. Archivio per le scienze mediche 1878; 2: 401-464

- Mosso A. Sulle variazioni locali del polso nell’antibraccio dell’uomo. 1878

- Mosso A. Die Diagnostik des Pulses in Bezug auf die localen Veränderungen desselben. 1879

- Mosso A. Sulla circolazione del sangue nel cervello dell’uomo. 1880 [Mosso Method]

- Mosso A. Applicazione della bilancia allo studio della circolazione delsangue nell’uomo. Atti R Accad Sci Torino 1882; XVII: 534–35. [Mosso’s balance]

- Mosso A. La Paura. 1884

- Mosso A. La peur; étude psycho-physiologique: étude psycho-physiologique. 1886

- Mosso A. Ueber die Gesetze der Ermüdung: Untersuchungen an Muskeln des Menschen. Archiv für Physiologie: 1890; 89-168

- Mosso A. La Fatica. 1891 [Ergograph and muscle fatigue]

- Mosso A. Die Temperatur des Gehirns : Untersuchungen. 1894

- Mosso A. Fisiologia dell’uomo sulle Alpi: studii fatti sul Monte Rosa. 1897

- Mosso A. Les exercices physiques et le développement intellectuel. 1904

- Mosso A. La fatigue intellectuelle et physique: intellectuelle et physique. 1908

- Moss A. La democrazia nella religione e nella scienza: studi sull’ America. 1908

Controversies

Incorrect Theory on Altitude Sickness

Mosso developed a key interest in mountain climbing during his lifetime, to the degree his daughter would document his adventures in a book titled Un cercatore d’ignoto. Mosso’s combined interests in science and altitude led him to ascend the Alps and study a vast range of topics ranging from the laws of human muscle fatigue to the analysis of behavioral reactions and the modifications of sleep architecture of monkeys at high altitude.

Amongst the topics Mosso studied, one was of the phenomena of respiration at altitudes above the “snow-line”. In 1898, Mosso incorrectly theorized that mountain-sickness was caused by the increased washing out of carbon dioxide from the blood in the lungs as opposed to a decrease in oxygen availability. The theory went against that proposed by Paul Bert decades earlier, and thus was deemed preposterous by some. One such critic was Joseph Barcroft, who believed ”…Mosso seems to have overlooked the fact that the body is exposed to what is practically a vacuum of CO2, whether it be at the Capanna Margherita or in his own laboratory at Turin’’.

References

Biography

- Foà P. Angelo Mosso – Commemorazione. Torino, 1911.

- Prof. Angelo Mosso (1846–1910) Nature. 1946; 157: 689–690

- Sandrone S et al. Angelo Mosso (1846-1910). J Neurol. 2012; 259(11): 2513-4

- Bibliography. Mosso, A. (Angelo) 1846-1910. WorldCat Identities

Eponymous terms

- Angeli A. Angelo Mosso’s Ergograph. Accademia di Medicina

- Lowe MF. The application of the balance to the study of the bodily changes occurring during periods of volitional activity. British Journal of Psychology. General Section 1936; 26: 245–62.

- Zago S, Ferrucci R, Marceglia S, Priori A. The Mosso method for recording brain pulsation: the forerunner of functional neuroimaging. Neuroimage 2009; 48 :652–656

- Sandrone S et al. Weighing brain activity with the balance: Angelo Mosso’s original manuscripts come to light. Brain. 2014 Feb;137(Pt 2):621-33

- Zhang G. Eponyms in Aortic Regurgitation. LITFL 2019

Lewis is an RMO at Royal Perth Hospital. He is currently interested in critical care medicine.