Case of Commotio Cordis

A 14 year old male is brought by ambulance in cardiac arrest post being struck to the chest with a softball, during a school sports carnival.

On arrival the paramedics found the patient receiving effective CPR by his sports coach. The initial rhythm showed ventricular fibrillation (VF), and prompt defibrillation was attempted; however the patient failed to revert back into a perfusing rhythm.

On arrival in hospital you asses the patient (who has now been in cardiac arrest for 40 minutes), and notice he is in a fine ventricular fibrillation on the monitor. IV access is secured and you start administering standard resuscitation drugs, and attempt defribrillation another 8 times, with no success. The patient’s family is now present in room, and you explain that their son has been in cardiac arrest for over an hour but is not responding to treatment. Afterwards you call the code and comfort the family.

Two days later, you receive the pathology report from the autopsy which stating the findings:

…a normal pericardial sac, the coronary arteries arises normally and free from atherosclerosis, the chambers and valves are proportionate, with normal myocardium, and atrial and ventricular septa…

The toxicological report comes back normal, and the forensic pathologist puts the cause of death down as commotio cordis.

What is Commotio Cordis?

Ventricular fibrillation and sudden death triggered by a blunt, non penetrating, and often innocent appearing unintentional blow to the chest without damage to the ribs, sternum, or heart (and in the absence of underlying cardiovascular disease) constitute an event know as commotio cordis, which translates from the Latin as agitation of the heart. Maron, B. Estes, M.(2010).NEJM,362:10

Epidemiology:

- More than 224 cases have been reported to the US Commotio Cordis Registry since 1995, however its estimated that many more cases have not been reported.

- Based on the Registry cases of commotio cordis the survival rate was 24%.

- 95% of cases affected males.

- Commotio cordis most frequently occurs in those aged between 10 and 18 years, however cases have been documented between the age of 7 weeks to 51 years-old.

- 50% of episodes occur during competitive sports, a further 25% occur during recreational sports, and the other 25% occurs during other activities that involve blunt force trauma to the chest wall, e.g. kick by a horse, violence act.

- Baseball has the highest incidence of commotio cordis, followed by softball, hockey, then the football codes.

Differential diagnosis

- Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy (HOCM)

- Long QT syndrome

- Brugada syndrome

- Myocardial infarction of childhood

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (ARVD)

- Viral myocarditis

- Anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA)

- Electrolyte abnormalities

[See Cardiovascular Curveball #003 for a case of HOCM and QT prolongation]

Pathophysiology of Commotio Cordis:

- Commotio Cordis is a diagnosis of exclusion.

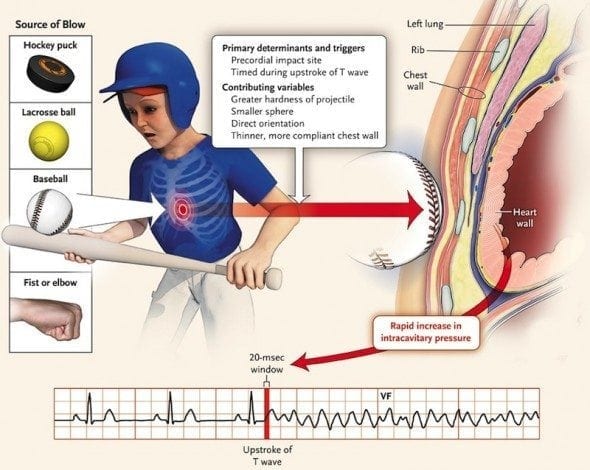

- Commotio Cordis is a primary arrhythmic event that occurs when the mechanical energy generated by a blow is confined to a small area of the precordium (generally over the left ventricle) and profoundly alters the electrical stability of the myocardium, resulting in ventricular fibrillation.

- In most instances (58%), the patient is struck on the chest by a projectile, commonly pitched, thrown, or batted, and the speed of the projectile is estimated to be 30-50mph on impact.

- The impact occurs within a specific 10-30 millisecond portion of the cardiac cycle. This period occurs in the ascending phase of the T wave, when the ventricular myocardium is repolarizing, during the transition from systole to diastole (relaxation). This small window of vulnerability makes commotio cordis a very rare event.

Clinical Presentation of commotio cordis:

- Generally a seemingly inconsequential non-penetrating blow to the chest is reported, followed by the patient collapsing suddenly, or a short time after the event, with no signs of life present.

- Patients generally present to ED unresponsive, apneic and pulseless with initial rhythm analysis generally showing ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia.

- Commotio cordis has a high mortality because most victims don’t get early access to effective CPR and defibrillation — the two key interventions that improve outcomes in out of hospital cardiac arrest.

- Standard advanced life support guidelines should be implemented focusing on airway, breathing, circulation with 30 compression: 2 breaths.

- Early recognition of a shockable rhythm, prompt defibrillation, and associated good quality CPR is the most effective treatment you can provide to the patient

- A precordial thump has been recommended in the past, however recent studies have shown it to be ineffective at terminating ventricular fibrillation, and should not delay prompt electrical defibrillation if available.

- Standard cardiac arrest drugs should be administered based on institutional protocols, however evidence is lacking, and should not delay defibrillation or CPR.

- Patients with return of spontaneous circulation should be transferred to an institution capable of providing post resuscitation care e.g. therapeutic hypothermia, ventilatory support.

Prevention of Commotio Cordis:

- Chest shields have been extensively studied, and encourage to be worn during sports like baseball and softball. Unfortunately, there is no evidence supporting chest shields as an effective means of reducing the impact of the blow to the vulnerable precordium or decreasing the incidence of commotio cordis. For a chest shield to be effective it would need to be extensively padded and supported, greatly impeding sports performance by limiting player movement. 18% of people who suffered commotio cordis were wearing a chest shield.

- Having public access to defibrillators at sporting events with high incidence of commotio cordis, and training people in the use of defibrillators and cardiopulmonary resuscitation, can help to improve the survival rates of people who suffer sudden cardiac arrest.

- Public education on the importance of preventing precordial blows. For example; baseball and softball coaches are being encouraged to educate players to step away or turn using the right shoulder to deflect balls rather than the chest wall.

Reference

- Doerer, J. et.al. (2007). Evaluation of Chest Barriers for Protection Against Sudden Death Due to Commotio Cordis. American Journal of Cardiology. 99, 857-859.

- Hamilton, S. Sunter, J. & Cooper, P. (2005). Commotio cordis – A report of three cases. International Journal of Legal Medicine. 119, 88-90

- Maron, B. & Estes, M. (2010). Commotio Cordis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 362(10), 917-927.

- Maron, B. Gohman, T. Kyle, S. Estes, M, Link, M. (2002). Clinical Profile and Spectrum of Commotio Cordis. Journal of American Medical Association. 287(9), 1142-1146.

- Nesbitt, A. Cooper, P. Kohl, P. (2001). Rediscovering commotio cordis. The Lancet. 357, 1195-1197

- Sharma, N. & Andrews, S. (2009). Commotio Cordis. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 70(1), 48-49

- Valani, R. Mikrogianakis, A. & Goldman, R. (2004). Cardiac concussion (commotio cordis). Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 6(6), 428-430

- Dimov V. Clinical Cases and Images: Zidane’s headbutt

Emergency nurse with ultra-keen interest in the realms of toxicology, sepsis, eLearning and the management of critical care in the Emergency Department | LinkedIn |

Damar Hamlin NFL player suffered cardiac arrest playing in Jan 23