Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

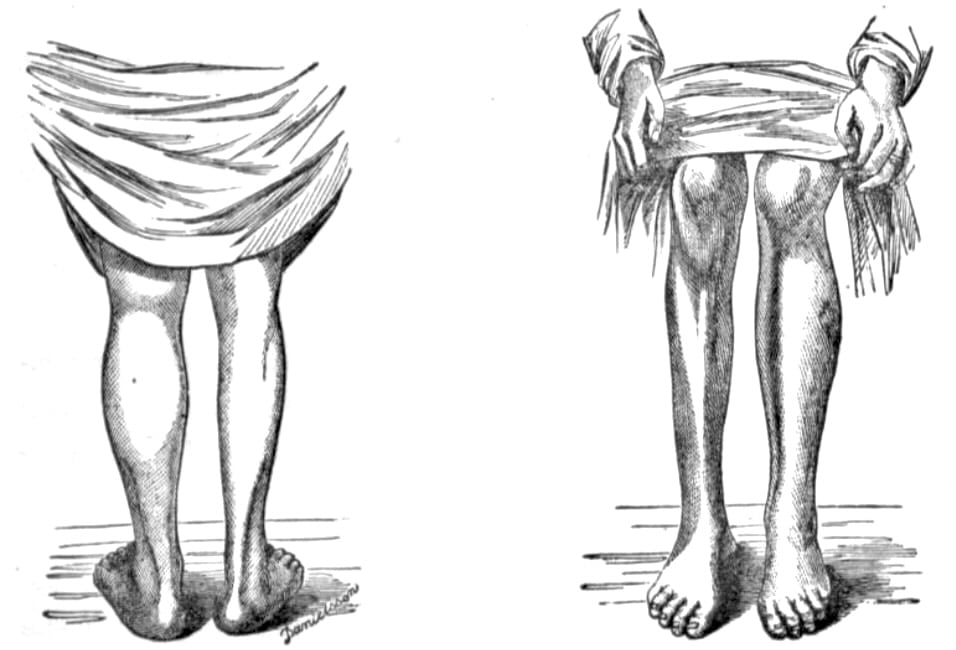

Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease (CMT) is one of the most common inherited neurological disorders, encompassing a group of genetically and clinically heterogeneous peripheral neuropathies. It typically presents as a slowly progressive distal muscle weakness and atrophy, usually beginning in the lower limbs during adolescence or early adulthood, often associated with foot deformities (e.g. pes cavus), distal sensory loss, and absent deep tendon reflexes. Involvement of the upper limbs follows later in the course of the disease.

CMT is classified into several subtypes based on clinical features, electrophysiological findings, mode of inheritance, and increasingly, genetic mutation. These include:

- CMT1 (demyelinating) – characterised by reduced nerve conduction velocities.

- CMT2 (axonal) – with relatively preserved velocities but reduced compound muscle action potentials.

- CMT4 (recessive demyelinating), CMTX (X-linked), and DI-CMT (dominant-intermediate) further enrich the classification landscape.

Epidemiology

CMT affects approximately 1 in 2,500 individuals globally. CMT1A, due to PMP22 gene duplication, is the most common subtype. Both sexes are affected, though some X-linked forms show male predominance.

Clinical Features

- Onset: typically in the first two decades of life.

- Motor: foot drop, distal weakness, wasting of the peroneal muscles, claw hand deformities in later stages.

- Sensory: numbness, tingling, impaired vibration and proprioception.

- Reflexes: absent ankle jerks.

- Deformities: pes cavus, hammer toes, scoliosis in some cases.

- Other: rarely associated with tremor, hearing loss, or diaphragmatic weakness in certain genetic forms.

Investigations

- Nerve conduction studies (NCS): to differentiate demyelinating (CMT1) from axonal (CMT2) types based on conduction velocities.

- Electromyography (EMG): to assess the pattern of denervation.

- Genetic testing: increasingly central in confirming diagnosis and subtype identification.

- Nerve biopsy: rarely required, but may show onion bulb formations in demyelinating types.

- MRI and musculoskeletal imaging: may aid in assessing muscle atrophy and skeletal abnormalities.

Management

No curative treatment exists. Management is supportive:

- Physical therapy and orthotics for mobility.

- Surgery for severe deformities.

- Genetic counselling for affected families.

The eponym honours Jean-Martin Charcot and Pierre Marie, who jointly described the condition in Paris in 1886, and Howard Henry Tooth, who independently reported similar findings that same year in his Cambridge MD thesis. The term “Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease” gained currency in the early 20th century to encompass these convergent descriptions of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy.

History of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

1855–1884 – Early reports of familial distal muscular atrophy were published by Virchow (1855), Eulenburg (1856), Hemptenmacher (1862), Friedreich (1873), Hammond (1879), Schultze (1884, 1930), and Ormerod (1884). While these accounts hinted at hereditary neuromuscular disorders, most lacked the consistent clinical pattern or peripheral nerve focus that would later define Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease. Retrospective analysis suggests many described divergent entities, including muscular dystrophies and anterior horn cell disease.

Exceptions include two particularly prescient observations from Nikolaus Friedreich (1825-1882) and Hermann Eichhorst (1849–1921) in 1873.

- Eichhorst, in Ueber Heredität der progressiven Muskelatrophie, documented a family across six generations with seven members personally examined, outlining what was likely a hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy.

- Friedreich, in Eigene beobachtungen, provided a detailed histopathological account of nerve fibre atrophy, Schwann cell hyperplasia, and spinal cord involvement — findings later confirmed in 1894 by Georges Marinesco (1863–1938) and now recognised as classical features of demyelinating CMT.

1886 – Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) and Pierre Marie (1853-1940) describe five patients with a familial, progressive atrophy of distal lower limbs – Sur une forme particulière d’atrophie musculaire progressives , proposing a spinal origin.

Though often criticised for attributing the disorder to myelopathy rather than neuropathy, they acknowledged diagnostic uncertainty and refrained from definitive localisation — a cautious insight given the limited tools of the time.

Est-ce done a une myelopathie que nous avons affaire? est-ce a une nevrite multiple peripherique? Ici, il faut bien l’avouer, la question devient beaucoup plus delicate, en presence surtout de ces cas ou il a existe soit des douleurs, soit des troubles divers de la sensibilite; bien que jusqu’a un certain point l’hypothese d’une myelopathie nous paraisse preferable il nous

semble difficile de se prononcer d’une facpn absolue

Is this a myelopathy? or multiple peripheral neuritis? Here, we must say, the question is more complicated, especially in the presence of cases with either pain or varied sensory disorders; although, up to a certain point, we prefer the hypothesis of myelopathy, it seems difficult to come to a firm conclusion.

1886 – Howard Henry Tooth (1856-1925) publishes his doctoral thesis in London describing a similar inherited neuropathy, correctly localising it to the peripheral nerves –The peroneal type of progressive muscular atrophy.

1912–1920s – Further pathological clarification emerges, differentiating hypertrophic (demyelinating) from neuronal (axonal) forms. In 1927, Sergei Davidenkov (1880–1961) attempted to classify the variegated inherited neuropathies into 12 categories based on clinical and genetic features – Über die neurotische Muskelatrophie Charcot-Marie Klinisch-genetische Studien. However, his classification faced several criticisms and never came into general use.

1968 – Dyck and Lambert propose a clinical-electrophysiological classification: Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy (HMSN) types I (demyelinating) and II (axonal).

1991 – Identification of PMP22 gene duplication as the cause of CMT1A by Lupski et al., marking a breakthrough in genetic understanding.

1993–2000s – Discovery of causative genes for CMT1B (MPZ), CMT2A (MFN2), CMTX1 (GJB1), and others.

2010s–present – Over 100 CMT-associated genes identified. Genetic testing becomes central to classification and diagnosis.

2020s – Novel therapies including gene modulation and antisense oligonucleotides are under clinical trial for subtype-specific interventions.

Associated Persons

- Friedrich Schultze (1848-1934)

- Hermann Eichhorst (1849-1921)

- Nikolaus Friedreich (1825-1882)

- Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) – French neurologist, foundational figure in modern neurology.

- Pierre Marie (1853-1940) – French neurologist, collaborator with Charcot, pivotal in early descriptions.

- Howard Henry Tooth (1856-1925) – English neurologist; first to suggest peripheral nerve origin

- Johann Hoffmann (1857-1919)

- Sergei Davidenkov (1880–1961)

- Peter J. Dyck (b. 1926) – Developed HMSN classification system.

- James R. Lupski (b. 1957) – American geneticist; discovered PMP22 duplication.

Alternative names

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth-Hoffman disease

- Dejerine-Sottas Syndrome (CMT3)

- Hereditary Neuropathy with Liability to Pressure Palsies (HNPP)

- GJB1 (Connexin 32)-related CMTX1

- Dyck Classification of Inherited Neuropathies

- PMP22 duplication disorders

References

Historical articles

- Virchow R. Ein Fall von progressiver Muskelatrophie. Virchows Archiv für pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für klinische Medizin 1855; 8: 537–540

- Friedreich N. Eigene beobachtungen. In: Über progressive Muskelatrophie; über wahre und falsche Muskelhypertrophie. 1873: 11

- Eichhorst H. Ueber Heredität der progressiven muskelatrophie. Berliner klinische Wochenschrift 1873; 10(42): 497–499 and 511-514

- Schultze F. Ueber eine eigenthümliche progressive atrophische Paralyse bei mehreren Kindern derselben Familie. Berliner klinische Wochenschrift 1884; 21: 649-651

- Dejerine J, Sottas J. Sur la névrite interstitielle, hypertrophique et progressive de l’enfance. Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances et mémoires de la Société de biologie, 1893; 45: 63–96

- Marinesco G. De l’amyotrophie de Charcot-Marie. Archives de médecine expérimentale et d’anatomie pathologique 1894; 6: 921-965

- Dawidenkow S. Über die neurotische Muskelatrophie Charcot-Marie Klinisch-genetische Studien. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie 1927; 107: 259-265 and 108: 344-445

- Dyck PJ, Lambert EH. Lower motor and primary sensory neuron diseases with peroneal muscular atrophy. I. Neurologic, genetic, and electrophysiologic findings in hereditary polyneuropathies. Arch Neurol. 1968 Jun;18(6):603-18.

- Charcot JM, Marie P. Sur une forme particulière d’atrophie musculaire progressive souvent familiale débutant par les pieds et les jambes et atteignant plus tard les mains. La Revue de médecine 1886; 6: 96-138 [English translation: Concerning a special form of progressive muscular atrophy: often familial starting in the feet and legs and later reaching the hands. Arch Neurol. 1967; 17(5):553-557]

- Tooth HH. The peroneal type of progressive muscular atrophy. Thesis; for the degree of M.D. in the University of Cambridge, 1886

- Hoffmann J. Weitere Beitrag Zur Lehre von der hereditären progressiven spinalen Muskelatrophie im Kindersalter nebst Bemerkungen über den fortschreitenden Muskelschwund im Allgemeinen. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Nervenheilkunde, 1897;10:292-320

Review articles

- Harding AE, Thomas PK. The clinical features of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy types I and II. Brain. 1980 Jun;103(2):259-80.

- Lupski JR, de Oca-Luna RM, Slaugenhaupt S, Pentao L, Guzzetta V, Trask BJ, Saucedo-Cardenas O, Barker DF, Killian JM, Garcia CA, Chakravarti A, Patel PI. DNA duplication associated with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1A. Cell. 1991 Jul 26;66(2):219-32

- Sturtz FG, Chazot G, Vandenberghe AJ. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease from first description to genetic localization of mutations. J Hist Neurosci. 1992 Jan;1(1):47-58.

- Rossor AM, Polke JM, Houlden H, Reilly MM. Clinical implications of genetic advances in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013 Oct;9(10):562-71

- Tazir M, Hamadouche T, Nouioua S, Mathis S, Vallat JM. Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies or Charcot-Marie-Tooth diseases: an update. J Neurol Sci. 2014 Dec 15;347(1-2):14-22.

- Kazamel M, Boes CJ. Charcot Marie Tooth disease (CMT): historical perspectives and evolution. J Neurol. 2015;262(4):801-5.

- Compston A. From the Archives, Brain, 2019; 142(8): 2538–2543

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |