Chironex fleckeri envenoming

aka Toxicology Conundrum 010

A 6 year-old girl was playing in shallow water at a beach in Northern Australia. She screamed and ran from the water before collapsing on the beach. Her legs and abdomen are covered in brown lines with surrounding erythema, and there appear to be tentacles stuck to her legs. She is unresponsive.

Questions

Q1. What is the likely diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

Envenoming by the multi-tentacled box jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri.

Chironex fleckeri is perhaps the most dangerous venomous animal in the world. There have been about 70 deaths in tropical Australian waters; most of the recent fatalities have been children on remote beaches. Death can occur within minutes due to systemic envenoming.

Q2. When and where does this condition occur?

Answer and interpretation

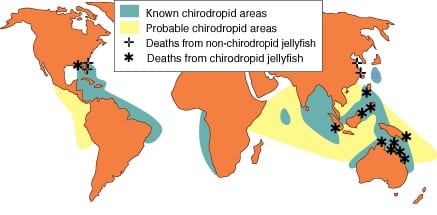

Box jellyfish envenoming occurs throughout Northern Australia, where it is an important public health threat. It is particularly well described in the “Top End” of the Northern Territory [Currie and Jacups, 2005].

- 84% of stings occur in water <1m deep.

- The official NT “stinger season” is from 1 October to 1 June – although 8% of stings occur outside of this time period, and stings have occurred in every month of the year!

Chironex fleckeri envenoming also occur throughout South-east Asia in countries such as Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and the Phillippines. Some envenomings may be due to a related “chirodropid” (muli-tentacled box jellyfish) called Chironex quadrigatus.

3. Describe the immediate and prehospital management of this patient.

Answer and interpretation

Recognise that this is a life-threatening situation and get help immediately – call an ambulance!

- Potential early life‑threats from Chironex fleckeri envenoming that require immediate intervention include cardiac arrest, hypotension or hypertension and cardiac arrhythmia.

- Assess “ABCs” and start cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- Smother the tentacles in vinegar and remove them

- Ideally pour a couple of liters of vinegar over the tentacles continuously for about 30 seconds.

- In cardiac arrest, undiluted antivenom, administered as a rapid IV push, may be life‑saving.

- If antivenom is available on arrival of the ambulance, all immediately available Box Jellyfish antivenom (at least 6 ampoules) should be given.

- Magnesium sulfate (10mmol IV) should be given if there is no response to antivenom.

- Do NOT attempt pressure-immobilisation bandaging (PIB)

- pressure actually triggers nematocyst firing and the venom acts so rapidly that PIB is unlikely to significantly reduce the systemic distribution of venom.

- Immediate transport to a medical facility.

4. Should the tentacles be removed?

Answer and interpretation

Yes!

- Adherent tentacles are present in about 30% of Chironex fleckeri stings in the Northern Territory.

- Nematocysts may continue to discharge leading to more severe envenoming if the tentacles are not removed.

The tentacles should be smothered in vinegar (as described above) and removed.

- In a life-threatening situation like this, the tentacles should be removed as soon as possible – I would not hesitate while waiting for vinegar to be applied.

- The tentacles can be removed by hand. This may result in a painful sting, but it will not be life-threatening and may help save the victims life.

What if vinegar is not available?

- There may be vinegar supplies at the beach, but ideally swimmers should take their own supply. Otherwise surf-lifesavers (if present) or the local fish-and-chip shop might be options!

- If there is no vinegar to be found, Coca-Cola may be used. Coke has a similar pH to vinegar, although some experts suspect that inorganic acids may not be as effective as organic acids in deactivating nematocysts.

- Urine is NOT effective! (see the video in Toxicology Conundrum 008)

- Avoid methylated spirits and other alcohols – they TRIGGER nematocyst firing!

Q5. Describe the use, indications, and effectiveness of anitvenom in this condition.

Answer and interpretation

The indications for Chionex fleckeri antivenom are:

- cardiac arrest due to Chironex fleckeri envenoming – all immediately available Box Jellyfish antivenom (at least 6 ampoules) should be given as a rapid IV push.

- evidence of systemic envenoming by Chironex fleckeri: collapse, hypotension or significant cardiac arrhythmia – three ampoules (3 × 20,000 units) IV diluted in 100 mL normal saline over 20 minutes

- Chironex fleckeri stings causing pain refractory to IV opioids – one ampoule (1 × 20,000 units) IV diluted in 100 mL normal saline over 20 minutes

CSL box jellyfish antivenom is an ovine IgG Fab available as 20,000 unit (~1.5-4 mL) ampoules.

- It can be given intramuscularly in the absence of intravenous access, but this route is pharmacokinetically unfavourable and probably ineffective (given the rapid distribution and action of the venom).

- Clinical experience thus far suggests that adverse reactions are uncommon (e.g. no documented adverse reactions from 22 cases in the Northern Territory).

The effectiveness of CSL box jellyfish antivenom is controversial and subject to ongoing research.

- Its use for pain refractory to opioids is unproven and based on anecdotal experience.

- Deaths have occurred despite the administration of antivenom.

- Some lab studies suggest that antivenom is only useful as a pretreatment.

Q6. Describe further management of this patient if they arrive at hospital undergoing bag-mask ventilation with a pulse, but are tachycardic and hypotensive.

Answer and interpretation

The patient is in a critical condition and shows evidence of ongoing life-threatening systemic envenoming by Chironex fleckeri.

Resuscitation, supportive care and monitoring –

- Rapid sequence intubation and ventilation.

- Administer 3 ampoules of antivenom (in 100 mL of normal saline over 20 min) and magnesium sulfate (10 mmol IV over 5-15 min) as the patient is haemodynamically unstable.

- Fluid resuscitation with intravenous crystalloid, and commencement of vasopressors/ inotropes (e.g. adrenaline).

- Early invasive monitoring, e.g. central venous access and PICCO / pulmonary artery catheterisation, to guide filling and inotrope/ pressor requirements.

- Meticulous supportive care and monitoring, including analgesia and wound care.

- Rule out other causes and complications of persistent tachycardia and hypotension

— E.g. Anaphylaxis to antivenom or other drugs if given, tension pneumothorax, other causes of hypoxia, etc.

Investigations –

- ECG (arrhythmia, ischemic changes, conduction blocks)

- Chest radiograph (acute pulmonary edema, check ETT position)

- FBC, UEC, troponin, CK

- ABGs

- Echocardiography

- Nematocyst sampling (not essential).

Decontamination and Enhanced elimination – nil

Antidotes – see resuscitation

Disposition – This patient requires ICU level care.

Q7. Describe the role of verapamil in the treatment of this condition.

Answer and interpretation

In the past, the calcium channel blocker verapamil was advocated as a treatment for Chironex fleckeri envenoming. Its use is no longer recommended.

- Verapamil was advocated by some because:

- isolated organ experiments suggested that Chironex fleckeri venom causes arterial constriction, reduced coronary blood flow and bradycardia – possibly due to increased intracellular calcium concentrations [abstract].

- Verapamil appeared to “delay death” in a mouse model of Chironex fleckeri envenoming [abstract].

- However:

- In a pig model of Chironex fleckeri envenoming, verapamil was associated with increased morbidity and mortality [abstract].

- Verapamil may potentiate hypotension and induce cardiac dysrhythmias.

Q8. Describe the role of magnesium in the treatment of this condition.

Answer and interpretation

Magnesium is advocated by some as an adjunct to antivenom in the treatment of Chironex envenoming.

- it was thought to help prevent cardiovascular collapse in a rat model with antivenom pretreatment (Ramasamy et al, 2004).

- a cell-based assay found that verapamil, magnesium and felodipine were all ineffective (Konstantakopoulos et al, 2009). Antivenom was only effective if used as a pretreatment.

References

- Box Jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri)

- Currie BJ, Jacups SP. Prospective study of Chironex fleckeri and other box jellyfish stings in the “Top End” of Australia’s Northern Territory. Med J Aust 2005; 183: 631-636. [full text]

- Hughes RJ, Angus JA, Winkel KD, Wright CE. A pharmacological investigation of the venom extract of the Australian box jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri, in cardiac and vascular tissues. Toxicol Lett. 2012 Feb 25;209(1):11-20. Epub 2011 Dec 2. PubMed PMID: 22154831.

- Konstantakopoulos N, Isbister GK, Seymour JE, Hodgson WC. A cell-based assay for screening of antidotes to, and antivenom against Chironex fleckeri (box jellyfish) venom. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2009 May-Jun;59(3):166-70. Epub 2009 Feb 28. PubMed PMID: 19254771.

- Pereira PL, Carrette T, Cullen P, et al. Pressure immobilisation bandages in first-aid treatment of jellyfish envenomation: current recommendations reconsidered. Med J Aust 2000; 173: 650-652. [full text]

- Ramasamy S, Isbister GK, Seymour JE, Hodgson WC. The in vivo cardiovascular effects of box jellyfish Chironex fleckeri venom in rats: efficacy of pre-treatment with antivenom, verapamil and magnesium sulphate. Toxicon. 2004 May;43(6):685-90. PubMed PMID: 15109889.

- Winter KL, Isbister GK, Jacoby T, Seymour JE, Hodgson WC. An in vivo comparison of the efficacy of CSL box jellyfish antivenom with antibodies raised against nematocyst-derived Chironex fleckeri venom. Toxicol Lett. 2009 Jun 1;187(2):94-8. Epub 2009 Feb 20. PubMed PMID: 19429250.

CLINICAL CASES

Toxicology Conundrum

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC