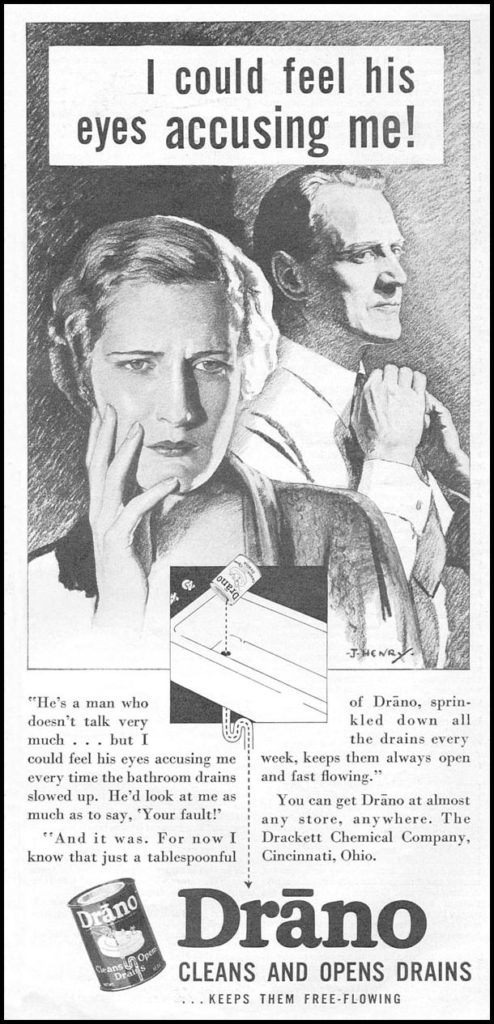

Corrosive ingestion

aka Toxicology Conundrum 032

A 4 year-old boy found some blue crystals in the sink. Thinking they might taste good, he scooped some into his mouth.

His immediate distress alerted his nearby father who found him crying from mouth pain, drooling and unable to speak or swallow. The boy’s father immediately called an ambulance and tried to rinse his son’s mouth with water. The boy vomited a few minutes later.

You are waiting in the resus room as the boy arrives.

Questions

Q1. What is the risk assessment?

Answer and interpretation

The history provided is concerning as it is consistent with the ingestion of a dangerous corrosive agent. For instance, solid preparations of sodium hydroxide (in combination with other agents) are commonly sold as drain cleaning products.

As with any risk assessment it is important to go to great lengths to determine the nature of the ingested substance. This may necessitate searching the home for drain cleaning products if the child’s father is unsure what the crystals were. If the product is known but you are still unsure of the contents then liaise with your regional Poison Information Centre. PIC staff can rapidly obtain the relevant information by searching their databases and, if necessary, by accessing information from the product’s manufacturer. If the substance cannot be identified, then assume the most likely ‘worst case scenario’, track the patients clinical progress and keep an open mind.

Remember the key components of a risk assessment:

- agent(s) – (including pH for corrosive agents)

- dose(s) – (including concentration and volume for corrosive agents)

- time(s) of ingestion

- patient factors – (e.g. comorbidities)

- clinical progress – (What is the patient like now? Does the story fit?)

Try to determine if the pellets were ingested or spat out. If the pellets were spat out corrosive injury may be limited to the mouth and lips. Determining what signs and symptoms the child has now will help refine the risk assessment.

However, two key tips to remember when assessing patient’s with corrosive injuries are:

- The absence of lip or oral burns does not exclude significant gastrosophageal burns.

- Signs and symptoms correlate poorly with the extent of gastrointestinal injury

Q2. What is the mechanism of toxicity from corrosive agents?

Answer and interpretation

Most corrosive agents cause direct chemical injury. Some (see Q4) may also cause severe systemic toxicity.

The extent of direct chemical injury depends on:

- pH

- concentration

- volume ingested

Acidic agents cause protein denaturation resulting in coagulative necrosis. Alkaline agents are more dangerous as they cause liquefactive necrosis resulting in deep and progressive mucosal burns. Other corrosive agents may have reducing, oxidizing, denaturing or defatting actions.

Q3. What are the corrosive agents are commonly available?

Answer and interpretation

Commonly available corrosive agents include:

- Sodium hydroxide — detergents, drain and oven cleaners, button batteries

- Sodium hypochlorite — bleaches and household cleaners (unintentional ingestion in children is generally benign, dilute solutions less than 150 mL do not cause significant corrosive injury)

- Ammonia — metal and jewelery cleaners, anti-rust products

- Hydrochloric acid — metal cleaners

- Sulfuric acid — drain cleaners, car batteries

- Button batteries — injury results from leakage of alkali, local electrical current discharge and direct pressure necrosis

Q4. What important corrosive agents may have severe systemic toxicity in addition to direct corrosive injury?

Answer and interpretation

Examples of corrosive agents that can cause severe systemic toxicity include:

- glyphosate (toxicity may be due to the herbicide’s polyoxyethyleneamine surfactant) — metabolic acidosis, shock, multi-organ dysfunction

- hydrofluoric acid — hypocalcemia

- mercuric chloride (inorganic mercury salts) — renal failure, shock

- oxalic acid — hypocalcemia, renal failure

- paraquat — pulmonary fibrosis, multi-organ dysfunction and shock

- phenol — coma, seizures, hepatotoxicity, renal failure

- phosphorus — hepatotoxicity, renal failure

- picric acid — renal failure

- potassium permangante — methemoglobinemia, multi-organ failure

- silver nitrate — methemoglobinemia

- tannic acid — hepatotoxicity

Q5. What clinical features are suggestive of a serious corrosive injury?

Answer and interpretation

Remember (at the risk of excessive repetition…):

- The absence of lip or oral burns does not exclude significant gastrosophageal burns

- Signs and symptoms correlate poorly with the extent of gastrointestinal injury

Corrosive ingestion may result in immediate symptoms of injury to the gastrointestinal tract:

- mouth and throat pain

- drooling

- odynophagia

- vomiting

- abdominal pain

Upper airway injury is the most important immediate life-threat. Laryngeal injury and edema presents with:

- progressive stridor

- hoarseness

- respiratory distress

Q6. How are the endoscopic findings of corrosive injuries graded?

Answer and interpretation

The endoscopic findings of corrosive injuries are graded as follows:

- Grade 0 — normal

- Grade I — mucosal edema and hyperemia

- Grade IIA — superficial ulcers, bleeding and exudates

- Grade IIB — deep focal or circumferential ulcers

- Grade IIIA — focal necrosis

- Grade IIIB — extensive necrosis

Q7. What are the complications of corrosive injury to the gastrointestinal tract?

Answer and interpretation

Complications include:

- Perforation

- Esophageal perforation and mediastinitis (chest pain, dyspnea, fever, subcutaneous edema)

- perforation of the stomach or small intestine resulting in peritonitis

- septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)

- Esophageal strictures — occurs in 30% of patients with Grade IIB or II injury on endoscopy

- Esophageal carcinoma — may occur over 40 years after a Grade II or III corrosive injury

Q8. What is the appropriate decontamination for a corrosive ingestion?

Answer and interpretation

This boy’s father did the right thing:

Rinse the mouth with water as an immediate first aid measure.

Important things NOT to do include:

- do not induce vomiting

- do not administer oral fluids

- do not administer activated charcoal

- do not attempt pH neutralisiation

- do not perform gastric lavage or insert an nasogastric tube (until endoscopy is performed)

Q9. Describe your approach to the management of this case?

Answer and interpretation

Use the Resus-RSI-DEAD approach.

Resuscitation:

Manage the patient in an area equipped for resuscitation with appropriately skilled staff.

Assess for life-threats – is there evidence of airway compromise? (see Q5)

- airway compromise from oedema may progress rapidly

- prepare to intubate early at the first signs of compromise, otherwise the edema may progress and a surgical airway become the only available option.

- Call for expert help (e.g. the most senior anesthetist available, with ENT back-up) and consider intubating while the patient is spontaneous breathing (e.g. gas induction in the operating theatre or an awake fiber-optic intubation in a cooperative patient).

Risk assessment (see Q1) — assess for evidence of corrosive injury (see Q5):

- symptoms and signs of gastrointestinal injury

- remember to check for corrosive injuries to other parts of the body such as the skin and eyes.

Supportive care and monitoring (including adequate analgesia)

- keep the patient NBM if symptomatic, pending endoscopic assessment.

- Do not insert a nasogastric tube until cleared of gastrointestinal injury (e.g. endoscopy)

Investigations, decontamination, enhanced elimination and antidotes:

- Perform a chest x-ray and abdominal x-ray for evidence of perforation if the child has suggestive symptoms or signs

- No further decontamination is needed

- Enhanced elimination is not useful

- No antidotes are available

Q9. What options for disposition are there in this case, and what are the determinants?

Answer and interpretation

Disposition is determined by the risk assessment and the child’s clinical progress.

The possibilities are:

- The child is asymptomatic at 4 hours post-ingestion, so a trial of oral fluids is performed. If this is tolerated well the child can be discharged (avoid discharging a child at night). Some experts advocate endoscopy following corrosive ingestion even in the asymptomatic patient.

- The child is symptomatic (e.g. throat pain, drooling, pain on attempting to swallow his own saliva, or has vomiting or abdominal pain). The child is kept NBM and admitted for observation and an endoscopy within 24 hours.

- The child has airway compromise. Take measures to secure the airway and arrange ICU admission.

- The child has evidence of gastrointestinal perforation, sepsis or hemodynamic instability. Arrange for an urgent surgical assessment and ICU admission.

Q10. Is there a role for antibiotics in the treatment of corrosive injury to the gastrointestinal tract?

Answer and interpretation

No — unless there is evidence of gastrointestinal perforation, which may result in mediastinitis or peritonitis and subsequent severe sepsis.

Q11. Is there a role for corticosteroids in the treatment of corrosive injury to the gastrointestinal tract?

Answer and interpretation

The use of corticosteroids for the treatment of gastrointestinal corrosive injuries from alkaline agents is controversial. However there is no evidence that corticosteroids are effective in preventing esophageal stricture formation. Furthermore, there are concerns that corticosteroids may actually increase mortality in Grade III injuries, increase the risk of infection or conceal the symptoms and signs of perforation.

References

- Muhletaler CA, Gerlock AJ Jr, de Soto L, Halter SA. Acid corrosive esophagitis: radiographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980 Jun;134(6):1137-40. PMID: 6770621

- Muñoz Muñoz E, et al (2001). Massive necrosis of the gastrointestinal tract after ingestion of hydrochloric acid. European Journal of Surgery, 167 (3), 195-8 PMID: 11316404

- Ong KL, Tan TH, Cheung WL. Potassium permanganate poisoning–a rare cause of fatal self poisoning. J Accid Emerg Med. 1997 Jan;14(1):43-5. PMID: 9023625; PMCID: PMC1342846

- Pace F, Greco S, Pallotta S, Bossi D, Trabucchi E, Bianchi Porro G. An uncommon cause of corrosive esophageal injury. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Jan 28;14(4):636-7. PMID: 18203301; PMCID: PMC2681160

- Pelclová D, Navrátil T (2005). Do corticosteroids prevent oesophageal stricture after corrosive ingestion? Toxicological reviews, 24 (2), 125-9 PMID: 16180932

- Riffat F, Cheng A. Pediatric caustic ingestion: 50 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22(1):89-94. Epub 2008 Oct 1. PMID: 18847446

- Zargar SA, et al (1992). Ingestion of strong corrosive alkalis: spectrum of injury to upper gastrointestinal tract and natural history. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 87 (3), 337-41 PMID: 1539568

CLINICAL CASES

Toxicology Conundrum

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at the Alfred ICU in Melbourne. He is also a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University. He is a co-founder of the Australia and New Zealand Clinician Educator Network (ANZCEN) and is the Lead for the ANZCEN Clinician Educator Incubator programme. He is on the Board of Directors for the Intensive Care Foundation and is a First Part Examiner for the College of Intensive Care Medicine. He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives.

After finishing his medical degree at the University of Auckland, he continued post-graduate training in New Zealand as well as Australia’s Northern Territory, Perth and Melbourne. He has completed fellowship training in both intensive care medicine and emergency medicine, as well as post-graduate training in biochemistry, clinical toxicology, clinical epidemiology, and health professional education.

He is actively involved in in using translational simulation to improve patient care and the design of processes and systems at Alfred Health. He coordinates the Alfred ICU’s education and simulation programmes and runs the unit’s education website, INTENSIVE. He created the ‘Critically Ill Airway’ course and teaches on numerous courses around the world. He is one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) and is co-creator of litfl.com, the RAGE podcast, the Resuscitology course, and the SMACC conference.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Twitter, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC