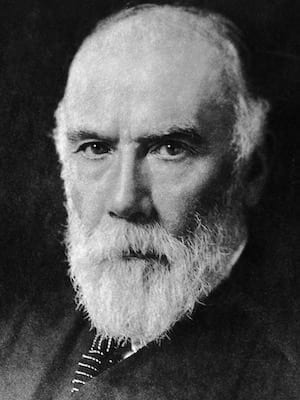

James Mackenzie

Sir James Mackenzie (1853-1925) was a Scottish general practitioner and cardiologist.

Mackenzie was a general practitioner and clinical investigator whose meticulous observations transformed the understanding of cardiac disease. Working from a busy practice in Burnley, he adapted the Dudgeon sphygmograph and later invented his multi-channel ink polygraph, allowing simultaneous recordings of venous and arterial pulses. With this simple but ingenious device, Mackenzie brought measurement and objectivity to the bedside, laying the foundations of modern clinical cardiology.

His tracings clarified the nature and prognosis of arrhythmias, showing the benign character of extrasystoles and sinus arrhythmia, and first demonstrating the loss of atrial contraction in what he termed “atrial paralysis” (now called atrial fibrillation). He defined the natural history of angina and ischaemic heart disease long before myocardial infarction was widely recognised. His landmark works include The Study of the Pulse (1902), Diseases of the Heart (1908–1918), and Symptoms and Their Interpretation (1909) which became standard references across Europe and America.

Despite later recognition as the leading cardiologist of his generation, Mackenzie never abandoned his roots in general practice. He championed the careful, long-term study of patients in the community, founded the Institute for Clinical Research at St Andrews (1919), and insisted that medicine must understand the earliest and often subtlest stages of disease. Knighted and elected FRS in 1915, he died in 1925 of the very angina he had so carefully documented, He is remembered as the first great clinical cardiologist, bridging practice, research, and human observation.

Biographical Timeline

- 1853 – Born April 12 at Pictonhill Farm, Scone, Perthshire, Scotland.

- 1865 – Attended Perth Academy; left at 15 to apprentice as a dispensing chemist in Perth.

- 1874–1878 – Entered University of Edinburgh Medical School after private Latin tuition; graduated M.B., C.M. in 1878.

- 1878–1879 – House physician, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

- 1879 – Entered general practice in Burnley, Lancashire, with Drs. William Briggs and John Brown.

- 1880 – Experienced the sudden death of a young obstetric patient from heart failure; epiphany that existing knowledge of heart disease was inadequate.

- 1882 – Awarded M.D. (Edinburgh) with thesis on Hemi-paraplegia spinalis.

- 1883–1885 – Began systematic clinical studies of cardiac symptoms, recording jugular venous and arterial pulses; adapted the Dudgeon sphygmograph.

- 1885 – Perfected a portable recording device with local watchmaker Mr. Shaw: the Mackenzie Ink Polygraph, capable of simultaneous tracings of jugular, radial, and apex beats.

- 1890 – Demonstrated that heart chambers could beat independently; described extrasystoles and their generally benign prognosis.

- 1892–1894 – Published on visceral pain and venous/liver pulses in Medical Chronicle and Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology.

- 1902 – Published The Study of the Pulse, establishing his international reputation.

- 1906–1907 – At age 54, moved to London, establishing himself as a heart specialist in Harley Street. Initially resisted by the “Giants” of the Royal College of Physicians, but later admitted as Fellow.

- 1907 – Elected to Association of Physicians of Great Britain and Ireland; invited to open discussion on the heart.

- 1908–1918 – Published successive editions of Diseases of the Heart, his magnum opus, translated into German, French, and Italian.

- 1913 – Appointed physician-in-charge, Cardiac Department, London Hospital.

- 1915 – Elected Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1915; knighted the same year.

- 1918 – Retired from London practice to St Andrews

- 1919 – opened the Institute for Clinical Research, focusing on the early stages of disease and involving local GPs.

- 1925 – Died January 26 in London after angina pectoris; buried in St Andrews.

Key Medical Contributions

The Ink Polygraph and the Birth of Modern Cardiology

In Burnley, Mackenzie developed his multi-channel ink-writing polygraph with the help of a local watchmaker, Mr. Shaw. First demonstrated at the BMA Toronto meeting (1906) and described in the BMJ (1908), it allowed simultaneous recording of jugular, radial, and apex beats.

The polygraph transformed clinical cardiology, enabling objective study of arrhythmias and venous waves. Mackenzie showed that many irregularities, such as extrasystoles and sinus arrhythmia, were benign, and clarified the natural history of conditions like atrial fibrillation.

Ironically, the polygraph was later adopted by criminology as the first “lie detector”, but its true legacy lay in the creation of clinical physiology at the bedside.

The radial pulse is the most serviceable of standards, a special method is employed to record it. A splint, C, is fastened to the wrist in such a manner that the pad of the steel spring falls on the radial artery and is pressed down by an eccentric wheel, 18, until a suitable movement is transmitted to the spring by the artery; then the broad tambour, C, is fitted on to the splint so that the knob, 12, falls on the moving spring. This wrist tambour is connected to the tambour, B, by India-rubber tubing, 22, 22, and the movements of the radial pulse are recorded by the lever, F. The shallow cup (receiver), E, is placed on the pulsation which it is desired to record, and the movement is conveyed to the lever, F , of the other tambour. In this way simultaneous with the radial pulse a record can be obtained of the apex-beat, carotid, jugular, or other pulses. To record the respiratory movements a bag can be substituted for the receiver, E. Mackenzie 1908

Atrial Fibrillation and Arrhythmias

Mackenzie was the first to record the disappearance of the ‘a’ wave from the jugular pulse and the presystolic murmur in mitral stenosis during atrial fibrillation, which he termed “atrial paralysis.” He distinguished harmless irregularities from dangerous ones, laying the groundwork for prognosis-based cardiology.

Working with Arthur Robertson Cushny (1866 -1926) and later Sir Thomas Lewis (1881-1945), Mackenzie linked his clinical tracings with experimental physiology. Though sceptical of the electrocardiograph, his observations were confirmed and extended by Lewis, who built the “new cardiology” on Mackenzie’s bedside insights.

Angina, Coronary Disease, and the Natural History of the Heart

Mackenzie’s Diseases of the heart (1908–1918) presented rich case histories of angina pectoris and myocardial ischaemia, including probable infarctions. His clinical notes suggested that coronary disease was far more common in early 20th-century Britain than contemporaries recognised.

His own experience with angina pectoris became part of his teaching. Post-mortem examination of his heart in 1925 confirmed extensive coronary sclerosis, fibrosis, and small infarcts. In many ways, Mackenzie lived, and died, the natural history of the disease he had done so much to describe.

Grant and I examined the heart very closely and we are agreed that there are amply sufficient old-standing changes at the apex of the heart to account for the first attack of pain described in his case notes. That attack of pain is strongly suggestive of coronary thrombosis, and the fibrosis at the apex is distributed in a way that also suggests thrombotic obstruction of an apical branch

Lewis, 1925

General Practice and “Mackenzie’s Puzzle”

Mackenzie never lost his identity as a general practitioner. He often said his greatest advance came from realising that the majority of his patients’ ailments were not explained by textbooks:

I was not long engaged in my new sphere when I realized that I was unable to recognize the ailments in the great majority of my patients. For some years I went blundering on, gradually falling into a routine, i.e. giving some drug that seemed to act favourably on the patient, till I became dissatisfied with my work and resolved to try and improve my knowledge by more careful observation.

Mackenzie 1919

Mackenzie’s puzzle became the cornerstone of academic general practice, inspiring later generations to see generalism as a discipline in its own right, rooted in long observation, uncertainty, and humility before patients.

War, “Soldier’s Heart,” and Anglo-American Cardiology

During WWI, Mackenzie advised on the establishment of the British Military Heart Hospital (1916) alongside Osler, Clifford Allbutt, and Thomas Lewis. Here they investigated the mysterious syndrome of “soldier’s heart” a functional cardiovascular disorder affecting recruits.

The American cardiologist Samuel Albert Levine (1891-1966), who worked with Mackenzie in 1917, sketched him as “a tall, burly man with all the directness of the North… at that time probably the most outstanding cardiologist in the world”.

This wartime collaboration helped knit together British and American cardiology, with Mackenzie’s emphasis on functional capacity “a heart is what a heart can do”, shaping the modern rehabilitation approach.

The Institute for Clinical Research at St Andrews

Retiring from London in 1918, Mackenzie founded the Institute for Clinical Research in St Andrews (1919). Its aim was to study the early natural history of disease by involving local general practitioners and systematically collecting case records.

This vision of community-based clinical research integrated with general practice was revolutionary. Though short-lived after his death, it anticipated modern primary care research networks and remains one of his most important legacies.

Major Publications

- Mackenzie J. Clinical report of a case of hemiparaplegia spinalis with remarks (Thesis). University of Edinburgh. 1882

- Mackenzie J. The study of the pulse, arterial, venous, and hepatic, and of the movements of the heart. Edinburgh Y.J. Pentland. 1902.

- Mackenzie J. Diseases of the heart. London: Hodder & Stoughton. 1908

- Mackenzie J. The Ink Polygraph. Br Med J. 1908 Jun 13;1(2476):1411

- Mackenzie J. Symptoms and their interpretation. London: Shaw. 1909

- Mackenzie J. Digitalis. Heart 1911;2(4)

- Mackenzie J. Principles of diagnosis and treatment in heart affections. London: Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton. 1916.

- Mackenzie J. The future of medicine. London: Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton. 1919

- Mackenzie J. Heart disease and pregnancy. London: Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton. 1921

- Mackenzie J. Angina pectoris. London: Henry Frowde, Hodder & Stoughton. 1923

References

Biography

- Montieth WBR. Bibliography With Synopsis of the Original Papers of the Writings of Sir James Mackenzie. London: Oxford University Press. 1930.

- Waterston D, Orr J, Cappell DF. Sir James Mackenzie’s Heart. Br Heart J. 1939 Jul; 1(3): 237–248.

- Stevenson I. Sir James Mackenzie, 1853-1953. Am Heart J. 1953 Oct;46(4):479-84.

- Sir James Mackenzie 1853-1925 Beloved Clinician. JAMA. 1966;196(6):591-592

- McConaghey RMS. Sir James Mackenzie, M.D. 1853-1925. General Practitioner. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1974 Jul; 24(144): 497–498.

- Krikler DM. Sir James Mackenzie. Clin Cardiol. 1988 Mar;11(3):193-4.

Eponymous terms

- Smith C, Silverman M. A letter from Sir James Mackenzie to Dr. Carter Smith, Sr. Circulation. 1975;51:212-217

- McCormick JS. James Mackenzie and coronary heart disease. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981 Jan; 31(222): 26–30.

- McMichael J. Sir James Mackenzie and atrial fibrillation–a new perspective. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981 Jul; 31(228): 402–406

- Murdoch JC. Mackenzie’s puzzle–the cornerstone of teaching and research in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47(423):656–658.

- Murdoch J, Denz-Penhey H. John Flynn meets James Mackenzie: developing the discipline of rural and remote medicine in Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2007 Oct-Dec;7(4):726. Epub 2007 Oct 10.

- Mackenzie B. Eponymythology: History of Second-degree AV block. LITFL 2018

Eponym

the person behind the name

MBChB (Hons), BMedSci, University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Currently working in Emergency Medicine in Perth, Australia. Lover of the outdoors and all things running, cycling and hiking. Varied interests including acute medicine and clinical oncology.

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |