Mallory-Weiss syndrome

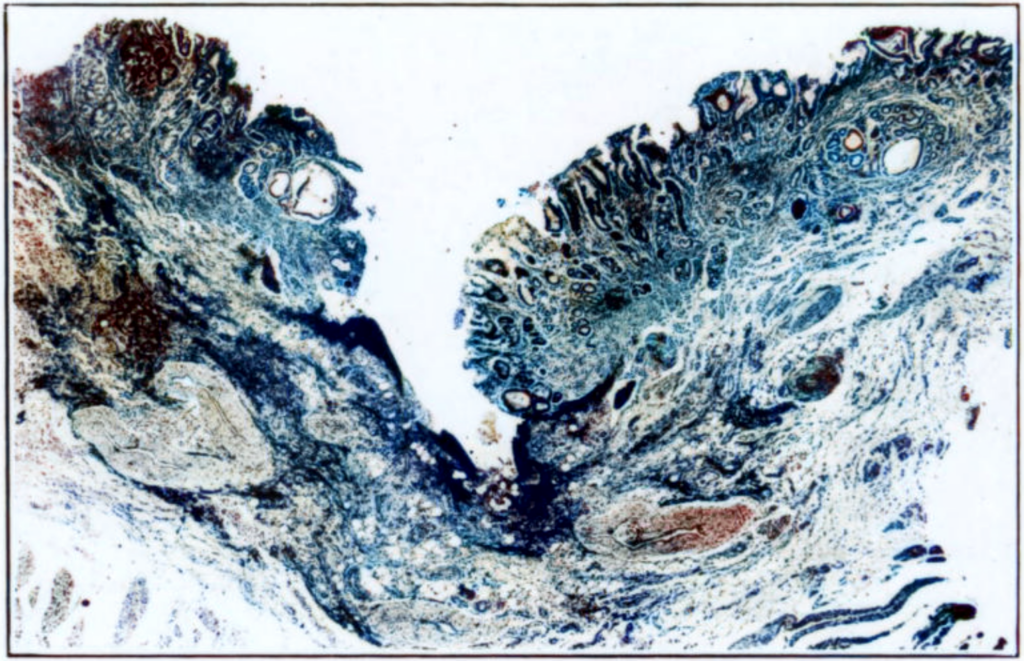

Mallory–Weiss syndrome (MWS) is a condition characterised by non-transmural, longitudinal mucosal lacerations (Mallory–Weiss tears) at the gastroesophageal junction, frequently following forceful retching, vomiting, or other causes of abrupt increases in intra-abdominal pressure. These tears are typically confined to the mucosa and submucosa, distinguishing them from full-thickness oesophageal rupture (Boerhaave syndrome).

Patients often present with:

- Haematemesis (bright red or coffee-ground emesis) – in ~85% of cases

- Melena, dizziness, or syncope in cases of significant blood loss

- Preceding retching or vomiting due to alcohol, gastrointestinal illness, or other triggers

- Occasionally epigastric or retrosternal pain; symptoms of shock in severe cases

Notably, up to 25% of patients have no identifiable risk factor or prodromal vomiting.

The syndrome results from sudden rise in intra-abdominal pressure transmitted across the gastroesophageal junction, leading to mucosal shear injury. This is often due to:

- Repetitive forceful vomiting or retching

- Coughing, convulsions, or straining

- CPR or endoscopic instrumentation (iatrogenic)

Tears typically occur along the gastric side of the lesser curvature or distal oesophagus, where mechanical tension and anatomic fixation converge. These are usually 2–4 cm in length.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

- Alcohol excess: present in 50–70% of cases

- Hyperemesis gravidarum, bulimia nervosa

- Hiatal hernia (variable association)

- GERD

- NSAID use, anticoagulation, cirrhosis with portal hypertension

- Endoscopy, TEE, or other transoesophageal procedures (iatrogenic)

- CPR-associated gastric insufflation and pressure injury

While historically tied to alcoholism, MWS is now recognised across a broad clinical spectrum, including teetotalers, young pregnant women, and post-operative patients.

Investigation

Initial evaluation focuses on stabilisation and risk stratification in suspected UGIB:

- Vital signs, orthostatic hypotension, signs of shock

- CBC: haemoglobin/hematocrit

- Renal function: BUN/Cr (upper GI bleeding may elevate BUN)

- Coagulation profile

- ECG and troponin if syncope or cardiac risk

Definitive diagnosis: Upper endoscopy (EGD): diagnostic and often therapeutic

- Single or multiple linear mucosal lacerations

- Active bleeding, adherent clot, or stigmata of recent haemorrhage

Differential Diagnosis

- Boerhaave syndrome – transmural oesophageal rupture; severe chest pain, mediastinal air, sepsis

- Oesophageal varices – cirrhotic patients; requires urgent banding or sclerotherapy

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Gastric or oesophageal malignancy

- AVMs or Dieulafoy lesion

Management

The majority of Mallory–Weiss tears (up to 90%) are self-limited and resolve without intervention.

Pharmacologic:

- IV PPIs (e.g., pantoprazole) to reduce gastric acid and stabilise clots

- Antiemetics to prevent further retching (e.g., ondansetron)

- Correct coagulopathy if present

Endoscopic therapy (for active bleeding or high-risk lesions):

- Epinephrine injection

- Thermal coagulation (MPEC, bipolar probe)

- Haemoclip application

- Band ligation in some settings

History of the Mallory–Weiss tear

1833 – Johann Friedrich Hermann Albers (1802–1865) published Über stechende Geschwüre der Speiseröhre und der Atemwege (“On perforating ulcers of the oesophagus and the airways”) He described penetrating oesophageal ulcers, often complicated by fistulae into the trachea and bronchi, identified at postmortem. Though distinct from Mallory–Weiss lacerations, this was the first systematic account of oesophageal ulcer disease.

..schrecklich endende Oesophagitis veranlasst, den Weg dieser Bildung nehmen und eine Öffnung zwischen Schlund und Luftröhre veranlassen…(“…a terribly ending oesophagitis takes this course, leading to an opening between the oesophagus and trachea…”)

Albers 1833

1879 – Heinrich Quincke (1842–1922) published Ulcus oesophagi ex digestione. He described three cases of oesophageal ulceration in the distal oesophagus, unrelated to carcinoma, corrosives, or trauma. Two patients died of massive haematemesis, one developed perforation into the pleura, and another had cicatricial stricture.

Quincke proposed the term “ulcus ex digestione” to describe an ulcer caused by the action of gastric juice upon the oesophageal mucosa, analogous to simple gastric ulcer. This was an early demonstration of oesophageal ulcer as a primary lesion and the first to connect it to fatal haematemesis.

Die beschriebenen drei Fälle zeigen… dass im unteren Theil der Speiseröhre Geschwüre vorkommen… die durch die verdauende Einwirkung des Magensaftes entstanden sind… und daher mit dem sogenannten einfachen Magengeschwür auf eine Linie gestellt werden müssen – Quincke 1879

The three cases described show… that ulcers do occur in the lower part of the oesophagus… arising from the digestive action of gastric juice… and must therefore be placed on the same line as the so-called simple gastric ulcer – Quincke 1879

1898 – Georges-Paul Dieulafoy (1839–1911) coins the term exulceratio simplex and provides the first comprehensive clinicopathological description. He described cases of sudden, fatal haematemesis due to minute ulcers eroding large submucosal vessels at the gastric cardia and fundus. He emphasised that these lesions were distinct from ordinary peptic ulcers and could bleed massively without warning.

…ces petites ulcérations, à peine visibles, peuvent déterminer des hémorragies foudroyantes et mortelles…- Dieulafoy 1898

…these small, scarcely visible ulcers can cause sudden and fatal haemorrhages…- Dieulafoy 1898

Although his emphasis was gastric rather than oesophageal, Dieulafoy’s description of exulceratio simplex (Dieulafoy lesion) provided a critical step in the evolving understanding of catastrophic haematemesis from small mucosal lesions at the gastroesophageal junction.

1929 – George Kenneth Mallory and Soma Weiss published their landmark description of 15 patients who developed upper gastrointestinal bleeding after episodes of severe vomiting. They identified a characteristic history of heavy alcohol use followed by persistent nausea, retching and vomiting.

During the past five years we have observed 15 patients, who after a long and intense alcoholic debauch developed massive gastric hemorrhages with hematemesis. … Autopsies in four of them showed fissure-like lesions at the cardiac opening of the stomach.

Mallory, Weiss 1929

Mallory and Weiss provided histopathological confirmation of mucosal tears extending into the muscularis layer.

1932 – Weiss and Mallory and Weiss rexpanded their observations with two fatal cases.

- Case 1: A “classical” presentation: a man with massive haematemesis after heavy alcohol intake; autopsy revealed a deep acute mucosal laceration rupturing an artery.

- Case 2: More atypical: a man with prior small-volume haematemesis, presenting with an “acute abdomen.” At autopsy, a longitudinal ulcerative lesion at the gastroesophageal junction was found, which had perforated into the mediastinum, causing empyema.

From these cases, Mallory and Weiss proposed a progression: acute laceration → chronic ulcer → perforation, suggesting that repeated vomiting could transform a mucosal tear into a chronic longitudinal ulcer. This concept might now be viewed as overlapping with conditions such as Barrett’s oesophagus.

1952 – Eddy Davis Palmer (1917-2010) in Observations on the vigorous diagnostic approach to severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, suggested that Mallory–Weiss lesions should be diagnosable clinically and via endoscopy, a prescient insight decades before this became standard practice.

1953 – John P. Decker, Norman Zamcheck (1916–1999), and George Kenneth Mallory reviewed 11 autopsy-confirmed cases, expanding the clinical profile and noting that not all cases were associated with alcoholism, challenging earlier assumptions.

1955 – Edward Gale Whiting (1907-1995) and Gilbert Barron (1915-1998) reported the first successful surgical treatment of a Mallory–Weiss tear.

1956 – James T. Hardy documented the first endoscopic diagnosis of Mallory–Weiss syndrome, cementing the diagnostic utility of endoscopy.

Modern era (post-1980s)

Endoscopic haemostasis (adrenaline injection, electrocoagulation, clips) became first-line therapy, with further studies clarifying risk factors, recurrence rates, and spontaneous healing patterns.

References

Historical references

- Albers JFH. Über stechende Geschwüre der Speiseröhre und der Atemwege. Journal der Chirurgie und Augenheilkunde 1833; 19: 1-9

- Quincke H. Ulcus oesophagi ex digestione. Deutsches Archiv für klinische Medicin. 1879; 24: 72-79.

- Dieulafoy G. Exulceratio simplex. L’intervention chirurgicale dans les hématémèses foudroyantes consécutives à l’exulcération simple de l’estomac. Bulletin de l’Académie nationale de médecine 1898; 39: 49-84.

- Dieulafoy G. Exulceratio simplex. Clinique médicale de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Paris, 1898: II.

Eponymous term review

- Palmer ED. Observations on the vigorous diagnostic approach to severe upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Ann Intern Med. 1952 Jun;36(6):1484-91.

- Decker JP, Zamcheck N, Mallory GK. Mallory-Weiss syndrome: hemorrhage from gastroesophageal lacerations at the cardiac orifice of the stomach. N Engl J Med. 1953 Dec 10;249(24):957-63.

- Whiting EG, Barron G. Massive hemorrhage from a laceration, apparently caused by vomiting, in the cardiac region of the stomach, with recovery. Calif Med. 1955 Mar;82(3):188-9.

- Hardy JT. Mallory-Weiss syndrome; report of case diagnosed by gastroscopy. Gastroenterology. 1956 Apr;30(4):681-5.

- Holmes KD. Mallory-Weiss syndrome: review of 20 cases and literature review. Ann Surg. 1966 Nov;164(5):810-20.

- Carr JC. The Mallory-Weiss Syndrome. Clin Radiol. 1973 Jan;24(1):107-12

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |