McMurray test

Description

McMurray test is used to evaluate individuals for tears in the meniscus of the knee.

First described in 1928 by Thomas Porter McMurray (1887-1949) and later refined in his 1934, 1942 publications and 1948 lecture.

Since the passing of McMurray in 1949 there have been myriad descriptions, modifications and variations of the originally described test, which were seldom referenced to McMurray directly. Over the last 10 years there has been more consistent descriptions of the McMurray test mostly referring to his 1948 lecture, but citing his 1942 publication.

From the history, and by a careful clinical examination, it is possible to diagnose most of the semilunar cartilage lesions in which the injury has occurred anterior to the lateral ligaments. Tears or displacements posterior to this point produce so few of the classical signs and symptoms that other methods of examination are necessary for their elucidation. In this connexion the use of manipulation of the injured joint has proved itself of value.

McMurray 1942

Modern interpretation of McMurray test

History of the McMurray test

1928 – McMurray designed a test intended to provoke meniscal tears of the external cartilage or posterior horn of the internal cartilage by passively fully flexing the knee and externally or internally rotating the tibia.

…the knee should be flexed completely, so that the heel rests on the buttock or as near this point as possible: the ankle is then grasped in the right hand, and the joint controlled by the left hand with the thumb and forefinger firmly grasping it on either side at the level of the joint to its posterior aspect, and behind the external and internal ligaments respectively. The ankle is now twisted by the hand, so that the knee is rotated inwards and outwards to its fullest extent, and if a lesion of the external cartilage or of the posterior portion of the internal cartilage is present a definite click can be felt under the finger or thumb of the left hand

McMurray 1928

1934 – McMurray offered the first modification of his test to more closely replicate the original injury. McMurray included the addition of abduction and adduction with the knee in full extension

… the knee-joint is first fully flexed so that the heel is placed almost on the buttock, then abduction of the leg and external rotation of the foot will bring to bear on the internal cartilage the exact same strain as occurs in the ordinary accident when an internal cartilage is displaced or torn. With the foot and leg held in this relation to the thigh, the knee is then slowly extended. If there is a lesion of the internal cartilage at any spot from the level of the attachment of the internal lateral ligament backward, a distinct click will be produced when the femur passes over the site of injury in the cartilage…Similarly, lesions of the external cartilage may be examined in almost the same way; after full flexion the joint is straightened with the leg adducted and internally rotated.

McMurray 1934

1942 – McMurray further refined his knee examination for evaluating knee meniscus tear. McMurray added passive knee extension to a right angle from full flexion following the end of tibial rotation and removed the component movements of abduction and adduction.

This version of the test is the most commonly cited, although most authors vary in their descriptions by including knee extension beyond 90° and/or the use of abduction and adduction.

McMurray 1942 test version [Br J Surg, 1942; 29: 407–414]

In carrying out the manipulation with the patient lying flat, the knee is first fully flexed until the heel approaches the buttock ; the foot is then held by grasping the heel and using the forearm as a lever. The knee being now steadied by the surgeon’s other hand, the leg is rotated on the thigh with the knee still in full flexion. During this movement the posterior section of the cartilage is rotated with the head of the tibia, and if the whole cartilage, or any fragment of the posterior section, is loose, this movement produces an appreciable snap in the joint.

By external rotation of the leg the internal cartilage is tested, and by internal rotation any abnormality of the posterior part of the external cartilage can be appreciated. By altering the position of flexion of the joint the whole of the posterior segment of the cartilages can be examined from the middle to their posterior attachments.

Thus, if the leg is rotated with the knee at right angles the cartilages in their mid-section come under pressure, but, anterior to this point, the pressure exerted on the cartilage is so diminished that accurate examination is impossible. When a loose segment of the cartilage is caught between the bones during the rotation, the sliding of the femur over the loose fragment is accompanied by a thud or click, which can sometimes be heard but can always be felt, and the size of the detached portion can be judged by the rocking of the tibia, and usually also by the severity of the sound produced.

This method of examination is not easy to master; the rotation requires a considerable amount of practice, and the whole procedure must be carried out systematically if success is to be attained. Probably the simplest routine is to bring the leg from its position of acute flexion to a right angle, whilst the foot is retained firs: in full internal, and then in full external rotation. Any abnormality in the cartilage structure in the area under examination will be discovered during the straightening of the joint.

The method, when correctly applied, gives very valuable evidence as to the existence of injury to the posterior segment of either cartilage

1948 – McMurray presented his final test modification in a lecture to the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

The patient lies flat with all the muscles relaxed. The surgeon grasps the foot on the affected side using the power of the forearm to produce the rotation of the limb. The knee and hip are now fully flexed until the heel approaches or touches the buttock and, holding the leg in a position of external rotation, the knee and hip are brought down to the extended position. The knee is again fully flexed and then slowly straightened with the leg in a position of full internal rotation. During these movements any abnormality of the semilunar cartilage can be defined not only in regard to its presence but also the site and extent of the lesion can be judged from the occurrence of a distinct painful click constantly occurring at the same point of extension

McMurray 1948

1957 – John R.Norcross M.D was the first to eponymise ‘McMurray’s sign’ as he described the 1948 modification of McMurray test.

McMurray’s sign is helpful in diagnosing a torn cartilage…During this procedure he should place his ear close to the patient’s knee. If the examiner hears or feels a definite “click” it is indicative of a torn medial cartilage.

Norcross 1957

1976 – Stanley Hoppenfeld described the McMurray test in his widely used text Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities and provided diagrams for instruction. Hoppenfeld replicated McMurray’s 1934 description but replaced the term abduction with valgus stress. He also recommended to internally and externally rotate the tibia once the leg was fully flexed in order to “loosen the knee joint” before commencing the test.

Clinical implication of McMurray test

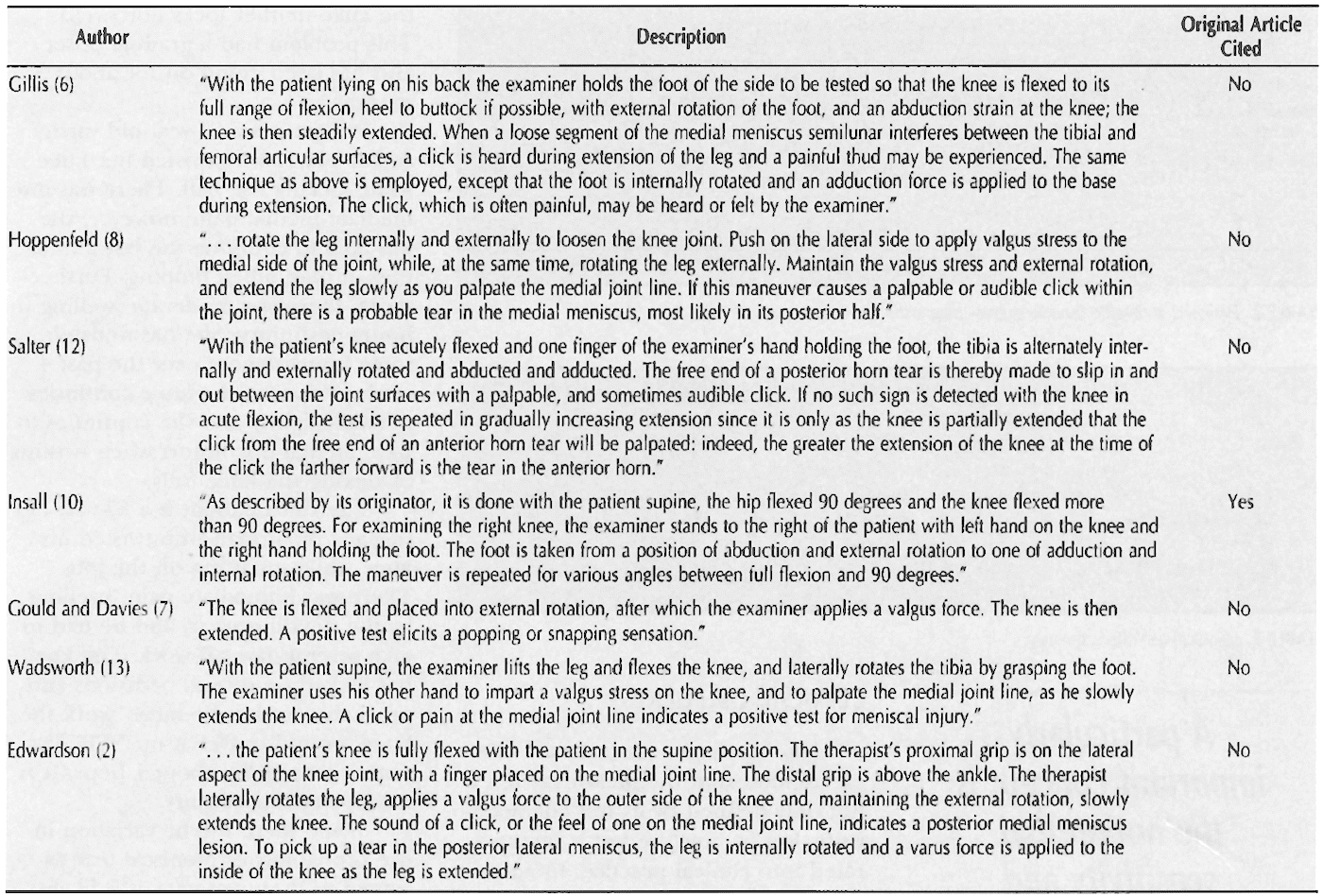

Sensitivity and specificity for the test varies greatly, mainly due to considerable inconsistency with regards to the description of the test (and the three published versions). The McMurray test was originally described with the knee being tested from full flexion to 90°, but its use and application now varies widely (See table below). Smith et al meta-analysis found Sensitivity 0.34-0.88; Specificity 0.5-0.93; LR+ 1.76-9.51 and LR- 0.24-0.76

Associated Persons

- Thomas Porter McMurray (1887 – 1949) [McMurray Test – 1928]

- Alan Graham Apley (1914 – 1996) [Apley Test – 1947]

Alternative names

- McMurray circumduction test

- McMurray’s test

References

Original Articles

- McMurray TP. The diagnosis of internal derangements of the knee. In: The Robert Jones Birthday Volume. A collection of surgical essays. Oxford Medical Press. 1928: 301-306

- McMurray TP. Certain injuries in the knee-joint. Br Med J. 1934; 1(3824): 709-13.

- McMurray TP. The semilunar cartilages. Br J Surg, 1942; 29: 407–414.

- McMurray TP. Internal Derangements of the Knee Joint. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1948; 3: 210-219.

Review Articles

- Norcross JR. Internal derangement of the knee joint including ligamentous tears. Surg Clin North Am. 1957 Feb;37(1):91-102.

- Hoppenfield S. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. 1976: 191-192

- Corea JR, Moussa M, al Othman A. McMurray’s test tested. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994; 2(2): 70-2.

- Stratford PW, Binkley J. A review of the McMurray test: definition, interpretation, and clinical usefulness. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995; 22(3): 116-20

- Solomon DH, Simel DL, Bates DW, Katz JN, Schaffer JL. The rational clinical examination. Does this patient have a torn meniscus or ligament of the knee? Value of the physical examination. JAMA. 2001; 286(13): 1610-20.

- Smith BE, Thacker D, Crewesmith A, Hall M. Special tests for assessing meniscal tears within the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2015; 20: 88-97.

- Gugliotti M, Storic L. The McMurray’s Test-A Historical Perspective. J Physiother Rehabil 2018; 2: 1

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

Irish doctor MB BCH BAO, NUI Gallway. Currently Emergency Medicine RMO in Perth, Western Australia. Interests in emergency medicine, GAA and exploring WA