Polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex hormonal condition that primarily involves menstrual dysfunction / anovulation and signs of hyperandrogenism

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a complex hormonal condition characterized by:

- Menstrual dysfunction/anovulation and

- Signs of hyperandrogenism

The exact etiology remains unknown, though familial and genetic links exist. Diagnosis is commonly based on the Rotterdam criteria. Many women experience delayed or missed diagnoses.

Emergency Department Relevance

Patients may present with:

- Ovarian cyst complications

- Pregnancy-related complications (e.g. miscarriage, preterm birth, gestational diabetes)

- Diabetes

- Psychiatric concerns

- PV bleeding (possible endometrial malignancy)

- Increased VTE risk (from obesity and oral contraceptive use)

History

- Originally called Stein-Leventhal syndrome

- First described in 1934 by Irving Stein (1887-1976) and Michael Leventhal (1901-1971)

Epidemiology

- Affects 8–13% of reproductive-aged women in Australia

- Incidence up to 21% among Indigenous women

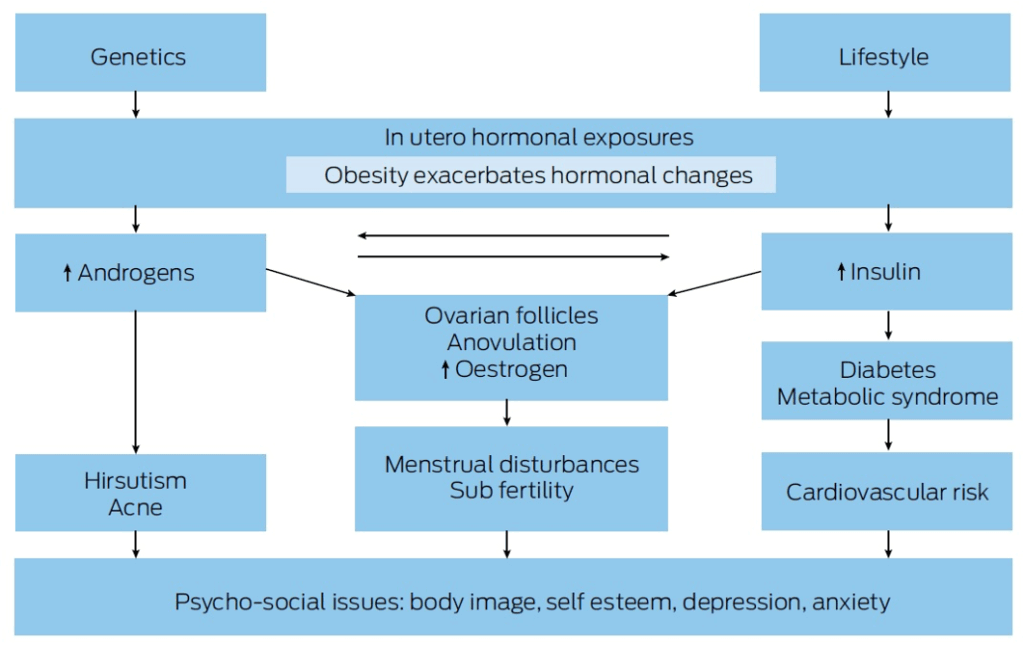

Pathophysiology

Likely multifactorial, involving:

- Genetic predisposition

- Intrauterine hormone exposure (e.g. anti-Müllerian hormone)

- Early weight gain

Metabolic Abnormalities:

- Androgen Excess: Elevated testosterone, androstenedione, DHEA-S

- Insulin Resistance: Hyperinsulinemia, risk of type 2 diabetes

- Dyslipidemia: Elevated LDL, triglycerides; reduced HDL

Clinical Features

Diagnosis:

Adults (Rotterdam criteria – 2 of 3 required):

- Oligo-/anovulation

- Clinical/biochemical hyperandrogenism

- Polycystic ovaries on ultrasound

Adolescents:

- Oligo-/anovulation

- Clinical/biochemical hyperandrogenism

Note: Ultrasound not recommended <8 years post-menarche

Cycle Definitions:

- <21 or >45 days (1–3 years post-menarche)

- <21 or >35 days or <8 cycles/year (>3 years post-menarche)

- 90 days for any cycle (>1 year post-menarche)

PCOS Phenotypes

| Phenotype | Features |

|---|---|

| A | Androgen excess + ovulatory dysfunction + polycystic ovaries |

| B | Androgen excess + ovulatory dysfunction |

| C | Androgen excess + polycystic ovaries |

| D | Ovulatory dysfunction + polycystic ovaries |

Ethnic Variations

- Caucasians: Milder phenotypes, higher BMI

- Middle Eastern/Hispanic/Mediterranean: Greater hirsutism

- SE Asians/Indigenous Australians: Higher metabolic risk, acanthosis nigricans

- East Asians: Lower BMI, milder hirsutism

- Africans: Higher BMI, metabolic features

Complications

- Infertility

- Obstetric Risks: Miscarriage, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes

- Hyperandrogenism: Hirsutism, acne, alopecia

- Weight Gain

- Endocrine: Increased diabetes risk

- Metabolic Syndrome: Obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance

- Cardiovascular Disease: Elevated risk factors

- Sleep Apnea: Obstructive sleep apnea common

- Endometrial Cancer: Due to chronic anovulation

- Acanthosis Nigricans: Marker of insulin resistance

- Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH)

- VTE Risk: Obesity, OCP use

- Psychiatric Disorders: Anxiety, depression, body image issues

Investigations

Blood Tests:

- FBE, U&Es, glucose, LFTs

- Beta-HCG (exclude pregnancy)

- TFTs, serum prolactin

- Free testosterone, FAI, bioavailable testosterone

- LH, FSH, androstenedione, DHEAS

- OGTT (especially if BMI >25 or high-risk ethnicity)

- Lipid screen (fasting)

Regardless of age, gestational diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes (5-fold in Asia, 4-fold in the Americas and 3-fold in Europe) are increased in PCOS, with risk independent of, yet exacerbated by obesity.

Glycaemic status should be assessed at baseline in all with people with PCOS and thereafter, every 1 – 3 years, based on presence of other diabetes risk factors.

In high risk women with PCOS (including a BMI > 25kg/m2 or in Asians > 23kg/m2, history of abnormal glucose tolerance or family history of diabetes, hypertension or high risk ethnicity) an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is recommended. Otherwise a fasting glucose or HbA1c should be performed.

An OGTT should be offered in all with PCOS when planning pregnancy or seeking fertility treatment, given increased hyperglycaemia and comorbidities in pregnancy.

If not performed preconception, an OGTT should be offered at < 20 weeks gestation, and all women with PCOS should be offered the test at 24-28 weeks gestation.

Ultrasound:

- Not for diagnosis <8 years post-menarche

- Preferred: transvaginal, if acceptable

- PCOM defined as:

- ≥20 follicles/ovary and/or

- Ovarian volume ≥10 mL

Management

- Lifestyle Modification:

- Diet, exercise, weight loss (5–10% improvement effective)

- Hyperandrogenism:

- Combined OCPs

- Anti-androgens: spironolactone, leuprolide, finasteride

- Physical methods: bleaching, laser

- Menstrual Irregularity:

- OCP or progestins

- Insulin Sensitizers:

- Metformin (menstrual regularity, glucose control)

- Avoid routine use of glitazones

- Infertility:

- First-line: Letrozole

- Alternatives: Clomiphene, gonadotropins

- Surgical: Ovarian drilling

- IVF if other infertility factors

- Dyslipidemia:

- Diet/exercise first

- Statins if needed

- Sleep Apnea:

- CPAP therapy

- Psychological Support:

- Screening and management of anxiety, depression, body image issues

Disposition

Management must be multidisciplinary and individualized.

Involved specialties may include:

- General Practitioner

- Endocrinologist

- Gynaecologist/Obstetrician

- Infertility Specialist

- Dietitian

- Psychologist

- Psychiatrist

- Paediatrician (if adolescent)

Care should be holistic and culturally sensitive.

References

Publications

- Teede HJ, Misso ML, Boyle JA, Garad RM, McAllister V, Downes L, Gibson M, Hart RJ, Rombauts L, Moran L, Dokras A, Laven J, Piltonen T, Rodgers RJ, Thondan M, Costello MF, Norman RJ; International PCOS Network. Translation and implementation of the Australian-led PCOS guideline: clinical summary and translation resources from the International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Med J Aust. 2018 Oct 1;209(S7):S3-S8.

Fellowship Notes

MSc, MBChB University of Manchester. Currently doctoring in sunny Western Australia, aspiring obstetrician and gynaecologist

Doctor at King Edward Memorial Hospital in Western Australia. Graduated from Curtin University in 2023 with a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery. I am passionate about Obstetrics and Gynaecology, with a special interest in rural health care.

Educator, magister, munus exemplar, dicata in agro subitis medicina et discrimine cura | FFS |