R&R In The FASTLANE 189

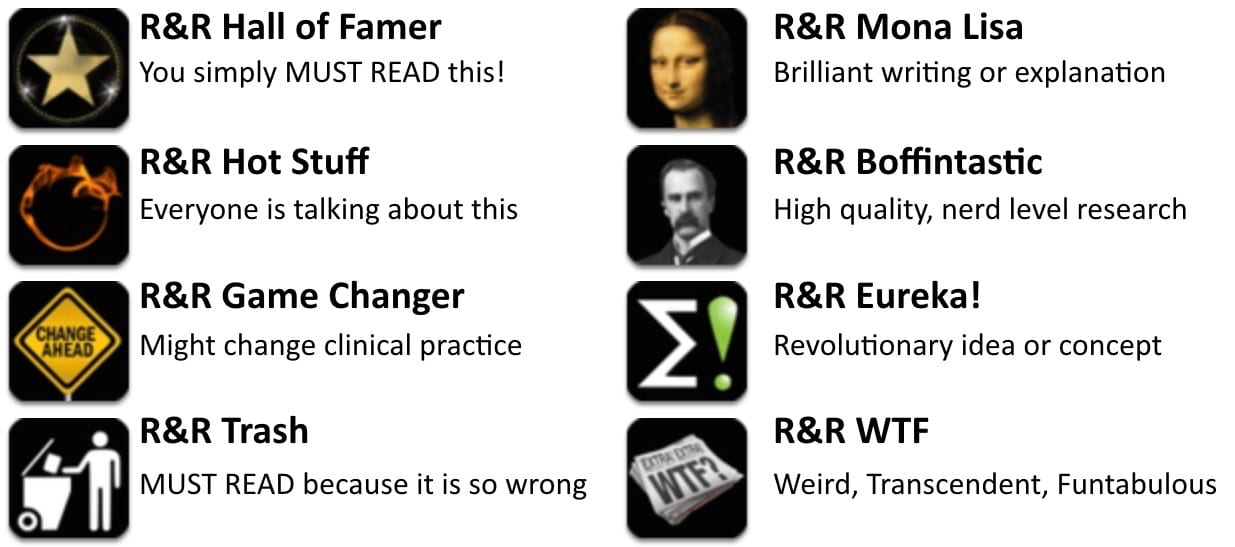

Welcome to the 189th edition of Research and Reviews in the Fastlane. R&R in the Fastlane is a free resource that harnesses the power of social media to allow some of the best and brightest emergency medicine and critical care clinicians from all over the world tell us what they think is worth reading from the published literature.

This edition contains 4 recommended reads. The R&R Editorial Team includes Jeremy Fried, Nudrat Rashid, Soren Rudolph, Anand Swaminathan and, of course, Chris Nickson. Find more R&R in the Fastlane reviews in the : Overview; Archives and Contributors

This Edition’s R&R Hall of Famer

Liu VX et al. The timing of early antibiotics and hospital mortality in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017. PMID: 28345952

- While it makes sense that expeditious administration of antibiotics to patients with sepsis should result in better outcomes, a number of studies and meta-analyses haven’t shown a clear relationship between early (< 6 hours) and very early (< 1-2 hours). This multi-center, retrospective study demonstrates a clear association between time and mortality in sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. While the benefit is modest in sepsis and severe sepsis (absolute difference 0.3% and 0.4% respectively) the benefit is more robust in septic shock (1.8%). Regardless, flaws with registry data abound. Mervyn Singer offers and editorial on time and antibiotics that is an excellent companion piece.

- Recommended by: Anand Swaminathan

Stecker EC, et al. Health Insurance Expansion and Incidence of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: A Pilot Study in a US Metropolitan Community. J Am Heart Assoc 2017. PMID: 28659263

- This study compares emergency medical care statistics for an urban metropolitan community in Oregon before and after the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in the USA. With the incidence of cardiac arrest approximately 17 percent lower post ACA than before it certainly brings home the potential implications of repealing and replacing the ACA.

- Recommended by: Virginia Newcombe

van der Hulle T, et al; YEARS study group. Simplified diagnostic management of suspected pulmonary embolism (the YEARS study): a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet 2017. PMID: 28549662

- The largest demonstration to date of the viability of 1000 ng/mL as the D-dimer cut-off for pulmonary embolism.

- Recommended by: RPR

- Further reading: Is the road to hell paved with D-dimers? (Emergency Medicine Literature of Note)

Kawano T, et al. H1-antihistamines reduce progression to anaphylaxis among emergency department patients with allergic reactions. Academic emergency medicine 2016. PMID: 27976492

- The conclusions of this study state that “early H1a treatment in the ED or prehospital setting may decrease progression to anaphylaxis”. This would definitely be new information, but I am not sure it is actually what the data shows. This was a retrospective chart review (with excellent chart review methods) looking at 2376 patients coded as having allergic reactions at 2 Canadian emergency departments. They excluded patients with anaphylaxis. When comparing patients who received H1 antihistamines to those who did not, they found a higher progression to anaphylaxis in the patients who were not treated (3.4% versus 1.9%, NNT = 44.74, 95% CI 35.36 to 99.67). Of course, a NNT assumes a causal relationship, and I don’t think that is what is going on here. You have to wonder why some people were given antihistamines and other were not.

- Were the groups equal? They don’t seem to be, with differences in history of allergy, allergen, and mode of arrival. Most importantly, 7.8% of the antihistamine group (as compared to only 2.8% of the no treatment group) was treated with epinephrine “before the development of anaphylaxis”. I am not sure why these patients would be given epinephrine if the clinician didn’t think they had anaphylaxis, so I wonder whether the chart review methods just failed to identify the true condition of the patient. Either way, treating these patients with epinephrine presumably treats anaphylaxis symptoms, and the 5% difference in epinephrine use is larger than the subsequent 1.5% difference they base their conclusions on. If you assume the patients given epinephrine actually had anaphylaxis, the rate of anaphylaxis was 9.7% with antihistamines and 6.3% without, supporting the exact opposite conclusion to the authors’.

- Bottom line: Antihistamines probably don’t prevent anaphylaxis, but this retrospective data can’t tell you either way

- Recommended by: Justin Morgenstern

Emergency physician with interest in education and knowledge translation. #FOAMed Fan | @jdfried |

Have you decided to stop doing the R&R’s? I loved them as a way to keep up with new articles. Hope you guys bring it back

They’re still coming!

We’re about to review the R&R process and get it recharged and humming along again 😉

Chris