Shock… Do We Know It When We See It?

Our curious and short human history is littered with betrayals.

We betray each other with alarming regularity – Judas Iscariot, Marcus Brutus, Benedict Arnold and Tokyo Rose are all part of our collective history, and, if not salient, at least provide insightful looks at our relationships.

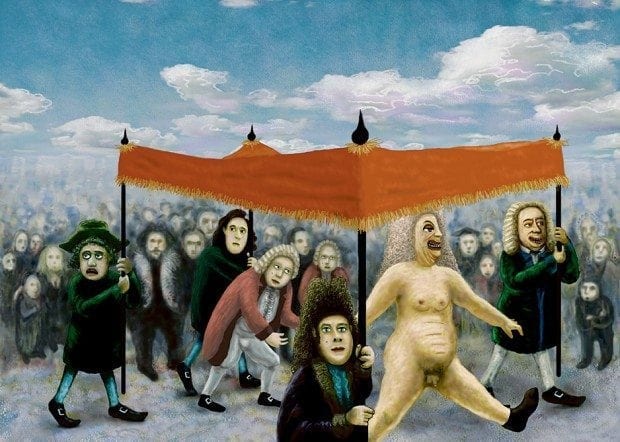

But, like the portly naked Emperor, we also betray ourselves, based on falsehoods and groupthink, parading with certainty through the town, convinced of our correctness. Medicine can sometimes be like this, with countless examples of teachings, tools, guidelines and texts that do not always have truth at their heart.

Once in a while, it’s worth examining the truths we think are solid, the advice we rely on, and make sure that we’re not striding unclad and righteous through our streets.

This strange little talk was designed to make us look at some of the things we hold dear in the assessment of shock, and perhaps discover that our ground is sometimes shaky, sandy, or even downright nude. It is only a view point, and an invitation for the listener to questions some of the things we think are good.

Because – in the assessment of shock, in an environment of reality, there are a few concepts that are actually bad.

- We don’t understand shock at all

- Our timeframe is bad

- Our tools we use to measure shock are bad

- The patients are bad

- The environment is bad.

And without acknowledging this, we may sometimes feel inappropriately confident.

1. Shock is unutterably complex.

Although it may be clinically useful to divide shock into our 5 usual pathophysiological groups, when an insult is introduced into a human, be it blood loss, fluid loss, trauma, burns, sepsis, anaphylaxis there is an extraordinary commonality between the massive and terrifying genomic storm that is induced. And although this is the current biochemical framework we are working on, it may in fact be a ‘metabolomic’ storm which is brewing, with a staggering number of intensely interrelated proteins being expressed. We talk about ‘cytokines floating around’ in shock, but the truth is so very, very much more complex. Is this important to us, as clinicians? Perhaps not, but we certainly ought to be wary of ‘magic bullets’ (in the clothing of single biological agents blocking a single pathway), and simplistic algorithms. Much of my understanding of this has come from the CISS study – the Critical Illness and Shock Study, an extraordinary journey into microarray gene sampling in critically ill patients, which began as a fishing expedition, and is being refined into some highly valuable and hopefully clinically relevant data.

2. The timeframes are against us.

Is it possible, with all that we know now about the genomic storm, and how it abates, that it may not matter at all what happens down the track in the Intensive Care Unit, but it is what happens in the early hours that makes a difference? (and do recall – this is all highly speculative, but worth contemplating how we think about shock). We know, that the earlier the shock is recognized and treated, the better the patients do. Which makes it imperative that we recognize shock as quickly as possible.

3. Our tools, on the whole, taken in isolation, are fairly appalling for identifying shock.

It is vital to know their limitations, and so understand when they may betray you with their normality, or, indeed, their variance. Physiological measures: Heart rate, Blood pressure, The ATLS guidelines for shock. All fallible. Measures of intravascular volume – all unreliable, particularly in the spontaneously ventilating patient (the frequent scenario in the early environment of reality). CVP, IVC filling on ultrasound, echo, lung ultrasound, passive leg raise. All have significant drawbacks, that need interpretation within the individual clinical scenario. Lactate – up until now thought to be the best of the bunch, but, what do we hear??? Perhaps lactate is a marker of compensatory response, and trying to look at radical clearance may not be an accurate measure of shock assessment and treatment.

4. The patients are bad.

It may not be the disease that’s killing them, but their co-morbidities.

5. The environment is bad.

Welcome to the world of ED. Where time and pressure are monumentally against the considered diagnosis of shock, a diagnosis that requires thoughtful contemplation and the review of the patient over time.

But – in the end, perhaps it is not all betrayal, daggers under the breastbone and purposeful trickery. Because in the right setting, and with considered understanding of the limitations of our knowledge, tools, substrate and environment, maybe we can look down at our rotund and naked form, and bedeck ourselves in something a little more modest. Whatever that may be. And who will be the best to decide?

You.

Check out the Full Prezzi presentation

References

- Thanks to Prof Simon Brown and Dr Glenn Arendts at Royal Perth Hospital, who run the CISS project and spent endless strange hours with me discussing the evolving results of their studies.

- The Critical Illness and Shock Study (CISS) – this is a prospective observational study of patients presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) with critical illnesses or injuries that compromise the cardiovascular and/or respiratory systems. Clinical and laboratory data will be used to better define and correlate clinical features, aetiology, pathophysiology and outcomes. The analysis of plasma, serum, leukocytes and DNA samples will enable us to investigate mechanisms of disease and novel biomarkers that may eventually facilitate improved diagnosis and therapy.

Plus:

- Cocchi MN, Kimlin E, Walsh M, Donnino MW. Identification and resuscitation of the trauma patient in shock. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007 Aug;25(3):623-42, vii.

- Harris T, Thomas GO, Brohi K. Early fluid resuscitation in severe trauma. BMJ. 2012 Sep 11;345:e5752. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5752.

- Mutschler M, Nienaber U, Brockamp T, Wafaisade A, Wyen H, Peiniger S, Paffrath T, Bouillon B, Maegele M; TraumaRegister DGU. A critical reappraisal of the ATLS classification of hypovolaemic shock: does it really reflect clinical reality? Resuscitation. 2013 Mar;84(3):309-13.

- Sandroni C, Cavallaro F, Marano C, Falcone C, De Santis P, Antonelli M. Accuracy of plethysmographic indices as predictors of fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2012 Sep;38(9):1429-37.

- ScanCrit — IVC Diameter and Hypovolaemic Shock

- Monnet X, Bataille A, Magalhaes E, Barrois J, Le Corre M, Gosset C, Guerin L, Richard C, Teboul JL. End-tidal carbon dioxide is better than arterial pressure for predicting volume responsiveness by the passive leg raising test. Intensive Care Med. 2013 Jan;39(1):93-100.

- Puskarich MA, Kline JA, Summers RL, Jones AE. Prognostic value of incremental lactate elevations in emergency department patients with suspected infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;19(8):983-5.

- Guly HR, Bouamra O, Little R, Dark P, Coats T, Driscoll P, Lecky FE. Testing the validity of the ATLS classification of hypovolaemic shock. Resuscitation. 2010 Sep;81(9):1142-7.

- Thiel SW, Kollef MH, Isakow W. Non-invasive stroke volume measurement and passive leg raising predict volume responsiveness in medical ICU patients: an observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):R111.

- Pretty much every EMCrit and Ultrasound Podcast podcast like, ever.

- Actually, the entire internet while we’re at it

- Brown SG. The pathophysiology of shock in anaphylaxis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2007 May;27(2):165-75, v. Review. PubMed PMID: 17493496.

- Bodson L, Vieillard-Baron A. Respiratory variation in inferior vena cava diameter: surrogate of central venous pressure or parameter of fluid responsiveness? Let the physiology reply. Crit Care. 2012 Nov 28;16(6):181. [

- Xiao W, et al; Inflammation and Host Response to Injury Large-Scale Collaborative Research Program. A genomic storm in critically injured humans. J Exp Med. 2011 Dec 19;208(13):2581-90.

Emergency physician. Lives for teaching and loves clinical work, but with social media, she is like the syndromic cousin in the corner who gets brought out and patted on the head once in a while | Literary Medicine | @eleytherius | Website |