Stroke Infarction: Basilar Artery

Basilar artery thrombosis is a devastating form of posterior circulation ischaemic stroke (POCI – posterior circulation infarction).

Severe neurological deficit and death are common.

Clues to the diagnosis will often be:

- Fluctuating initial symptoms of altered conscious state

- In combination with:

- Brainstem signs (usually ophthalmoplegias)

- Vomiting is also common

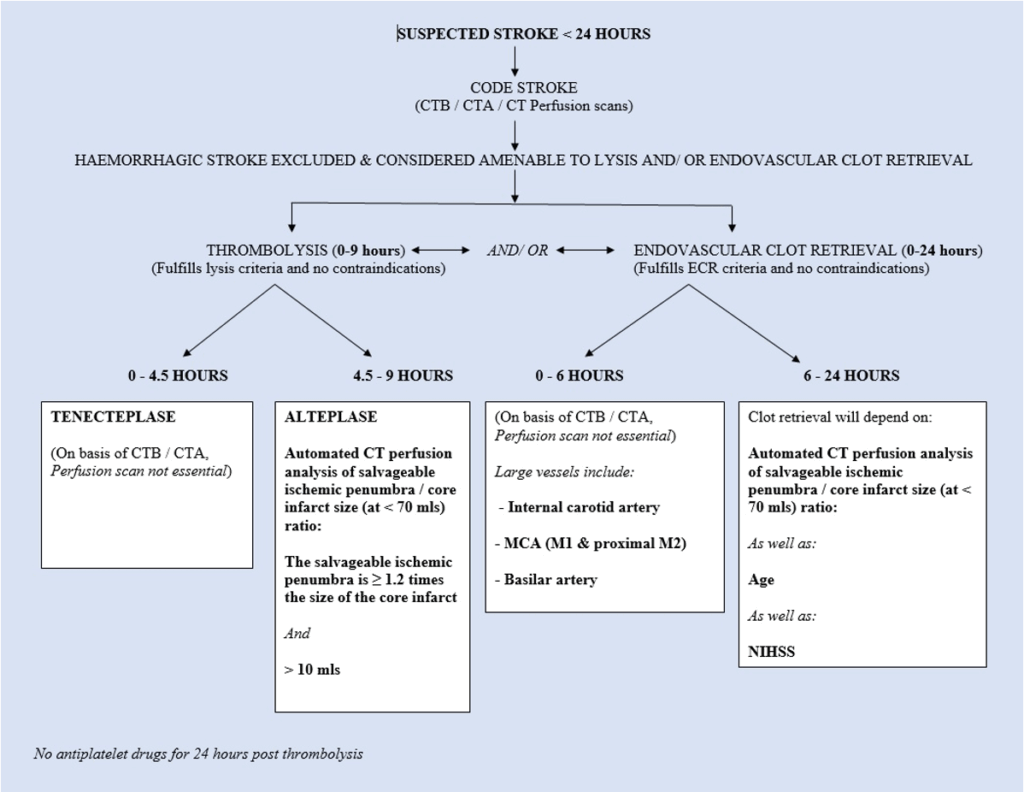

CT angiogram or MRI/MRA are required to confirm the diagnosis.

CT perfusion scanning assists in management decisions.

Good outcomes are only possible when the condition is considered and aggressively treated.

This is critical because of the severe consequences if missed and because thrombolysis and/or endovascular clot retrieval may provide life-saving treatment and good neurological outcomes.

- Therapeutic window for thrombolysis: up to 9 hours from symptom onset

- Therapeutic window for endovascular clot retrieval: up to 24 hours, supported by the DAWN trial

See also:

Pathophysiology

In its fully developed form, the syndrome is one of a “locked-in” state: unconsciousness and quadriparesis.

Some patients may present with partial or progressive occlusion, with limited ischemic injury and a better prognosis.

Normally, blood flows anterogradely from the vertebral arteries to the basilar artery and into terminal branches. If the proximal basilar artery is slowly occluded, collateralisation may occur, even with retrograde flow from PCAs.

Causes:

- Thrombosis or embolism

- Arterial dissection (rare; usually involves extracranial vertebral artery with occasional basilar extension)

Clinical features

Typical triad:

- Altered conscious state (may fluctuate initially)

- Brainstem deficits – especially ophthalmoplegias

- Vomiting

In comatose patients, suspicion relies on preceding transient symptoms, sometimes hours or days before.

Suggestive prodrome:

- Transient LOC

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diplopia

- Dysarthria

- Bilateral visual disturbance

- Vertigo, especially with hearing loss

- Quadriparesis or sensory loss

In the fully developed syndrome:

- Unconsciousness

- Quadriparesis (variable “locked-in” state)

- Decorticate posturing

- Dysconjugate eye movements, cranial nerve III and VI signs

- Pupillary abnormalities

- Bilateral upgoing plantar responses

Investigations

Blood tests:

- FBC

- U&Es / glucose

- Coagulation profile

- Group and save

- CRP / ESR

ECG:

- To detect arrhythmias, e.g. AF

CT angiogram (CTA):

- Initial scan to exclude haemorrhage

- Confirms basilar artery thrombosis

- Dense cerebral arteries may suggest thrombosis

MRI / MRA:

- Most sensitive/specific for basilar stroke

- Shows extent of brainstem infarction

- Often limited by availability or patient condition

Catheter angiography:

- Gold standard, but rarely needed due to quality of CTA/MRA

Management

1. ABCs:

- Prioritise airway and consciousness

- Intubation/ventilation may be required

2. Check BSL and correct accordingly

3. Thrombolytic therapy:

- Offers best survival/improvement chance

- Window: up to 9 hours

- Heparin not generally used

4. Endovascular clot retrieval:

- Includes mechanical embolectomy and stenting

- May be used:

- As primary therapy

- Post-thrombolysis

- Therapeutic window: up to 24 hours, due to:

- DAWN trial findings

- High mortality without intervention

Disposition

Initiate CODE STROKE immediately upon diagnosis or high suspicion.

Appendix 1

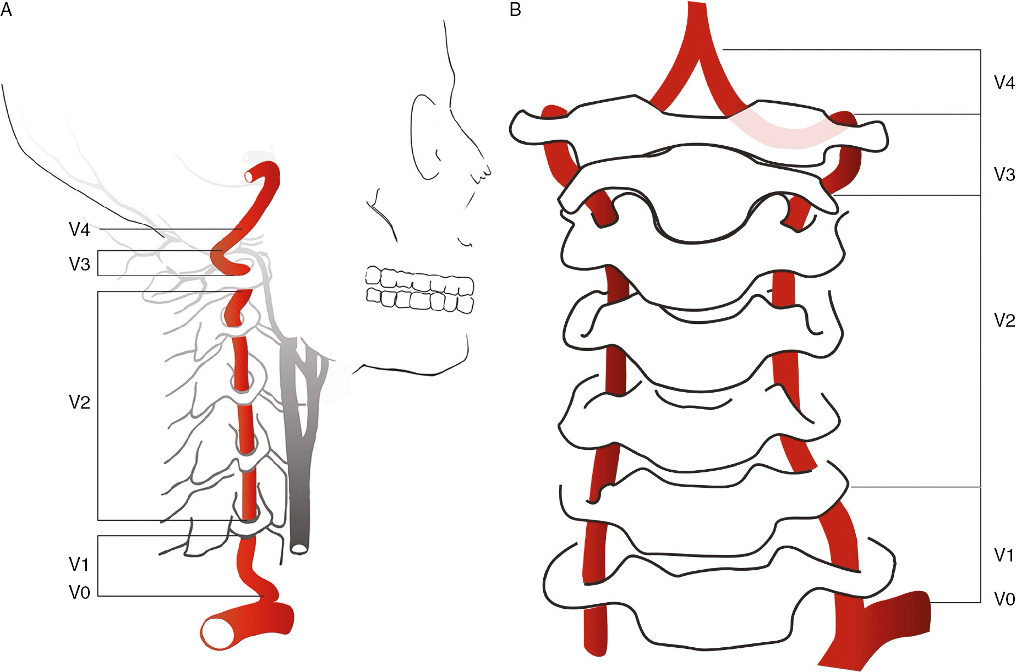

Vertebral artery anatomy:

The vertebral artery is typically divided into 4 segments:

- V1 (Preforaminal): From the subclavian origin to the transverse foramen of C6

- V2 (Foraminal): From the transverse foramen of C6 to the transverse foramen of C2

- V3 (Atlantic, extradural or extraspinal): From C2 to the dura

- V4 (intradural or intracranial): Within the dura to the confluence that forms the basilar artery

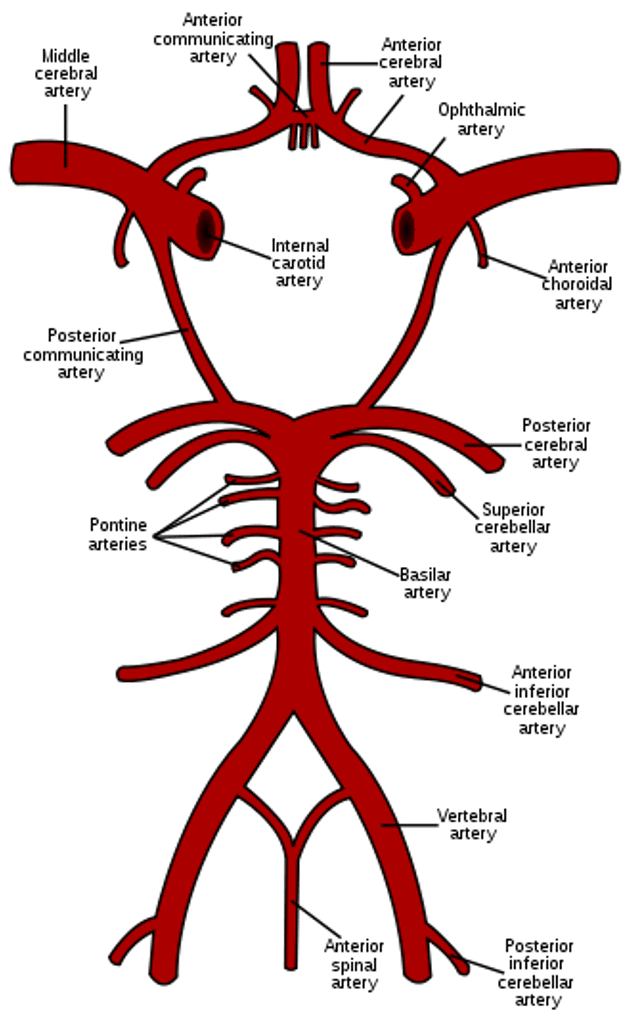

The posterior fossa arterial circulation

Appendix 2

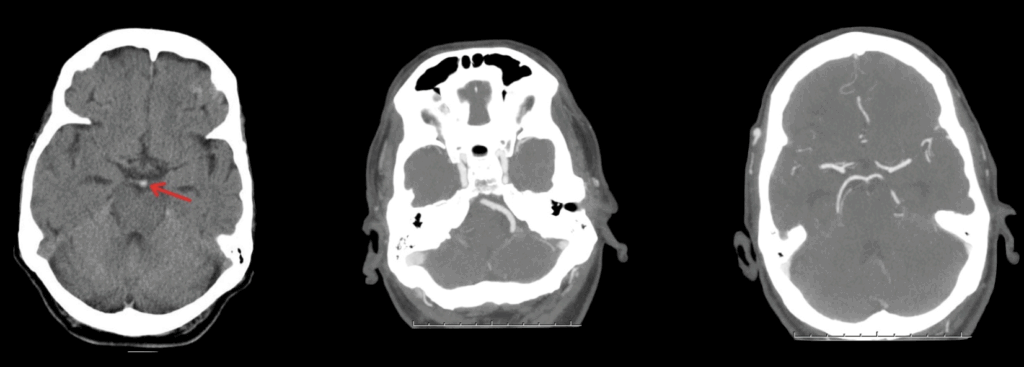

Case Study 1: Basilar artery thrombosis in a 78 year old male

LEFT: A plain CT scan may (but also may not) detect a hyperdense basilar artery (red arrow) to suggest the diagnosis. A CT angiogram however will be necessary to definitively make the diagnosis

MIDDLE: The left vertebral artery is seen, but not the right.

RIGHT: The posterior inferior cerebellar arteries are seen, but the basilar artery is not.

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

References

Publications

- Cole W. A physico-medical essay concerning the late frequency of apoplexies. 1693

- Fisher M. Occlusion of the internal carotid artery. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1951 Mar;65(3):346-77

- Nogueira RG et al; DAWN Trial Investigators. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 Hours after Stroke with a Mismatch between Deficit and Infarct. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 4;378(1):11-21.

- Tremonti C, Thieben M. Drugs in secondary stroke prevention. Aust Prescr. 2021 Jun;44(3):85-90.

- Clinical Guidelines for Acute Stroke Management – National Stroke Foundation

- Brazis PW, Masdeu JC, Biller J. Localization in Clinical Neurology. 8e 2021

- Fuller G. Neurological Examination Made Easy. 6e 2019

- O’Brien M. Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System. 6e 2023

FOAMed

- Beech G. CT Case 083. LITFL

- Davidson J. CT Case 061. LITFL

Coni R. Neuro 101: Cerebral Hemispheres. LITFL - Nickson C. Stroke Thrombolysis. LITFL

Fellowship Notes

MBBS DDU (Emergency) CCPU. Adult/Paediatric Emergency Medicine Advanced Trainee in Melbourne, Australia. Special interests in diagnostic and procedural ultrasound, medical education, and ECG interpretation. Co-creator of the LITFL ECG Library. Twitter: @rob_buttner

Educator, magister, munus exemplar, dicata in agro subitis medicina et discrimine cura | FFS |