Subungual haematoma

A subungual haematoma is a collection of blood under the fingernail or toenail, most commonly resulting from direct blunt trauma that compresses the nail against the distal phalanx. The injury is often acutely painful due to increased pressure between the nail plate and nail bed. Typical presentations include throbbing pain and visible dark discoloration beneath the nail.

These injuries are frequently encountered in emergency departments and minor trauma clinics, particularly among manual labourers, athletes, and children. They can also result from repetitive microtrauma, notably in long-distance runners or those wearing ill-fitting footwear.

Although often benign, larger haematomas may be associated with distal phalangeal fractures or nail bed lacerations, and may warrant decompression (trephination) or even nail removal and repair in selected cases.

Trephination is the standard of care for acutely painful haematomas, with excellent outcomes and low complication rates. Historically, a variety of techniques have been used — from heated paperclips to modern electrocautery and hollow bore needles. Notably, acrylic nails are a contraindication for electrocautery due to ignition risk.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

- Most common in adults due to occupational and sports-related trauma.

- Frequently affects the great toe or dominant hand fingers.

- Runners, dancers, and workers in construction or trades are disproportionately affected.

- Risk factors include tight footwear, coagulopathy, and anticoagulation therapy.

Clinical Assessment

- History: Usually acute onset of pain after direct crush injury. Repetitive trauma less painful but more chronic.

- Examination: Nail discoloration, tenderness, swelling. Assess neurovascular status.

- Investigations: X-rays indicated for suspected phalangeal fracture. Nail bed lacerations are often occult.

- Differentials: Subungual melanoma (chronic cases), melanonychia, nail-bed tumours. Melanocytic lesions typically spare the proximal nail plate.

Treatment Options

Wait and See:

- Small, painless haematomas <25% of nail area usually need no intervention.

- Patients who are not experiencing significant pain at rest, should not have trephination performed, and can be treated with simple analgesia, rest, ice, and a protective splint.

Active Therapy: Nail removal

- Rarely indicated.

- Only in cases where the nail is avulsed or lifted; or suspected nail bed laceration (especially with open fracture)

- Outcomes not better, but costs higher

Active Therapy: Trephination

- First-line therapy for acutely painful haematomas within ~48 hours (after which the haematoma becomes less amenable to drainage)

- Trephination gives good cosmetic and functional result in both adults and children as long as no other fingertip injury is present.

Trephination Method

- Clean the nail prior to trephination to avoid introducing infection

- No anaesthesia typically needed; decompression alone relieves pain.

Trephination Techniques

- Hot Cautery; heated paperclip (traditional, risk of injury/infection)

- Electrocautery (fast, avoid in acrylic nails)

- Hollow needle / IV cannula (manual twisting, safer)

Hot Cautery (paperclip) Method

This method involves applying a heated metal point to the nail, to relive the haematoma; this can be easy as heating paper clip, or using specially designed devices. Importantly this should not be done in a patient with acrylic nails. Acrylic nails are highly flammable and an alternate method should be chosen.

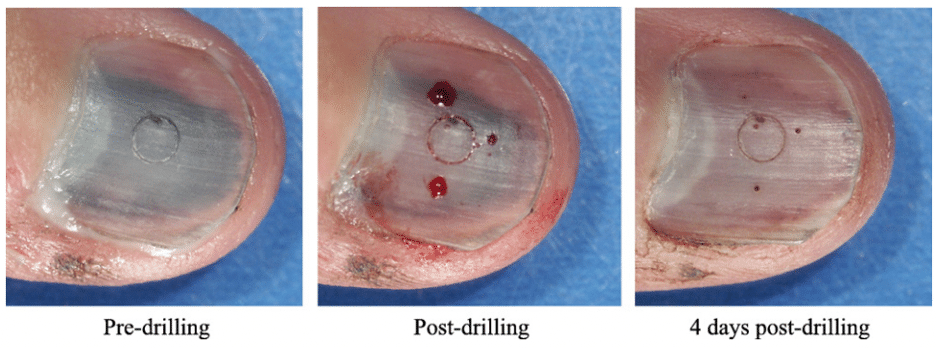

Drilling:

In the absence of a cautery device, a simple needle can be used. A gentle “drilling” technique with a standard cannula usually achieves good effect, essentially rotating side to side until blood expresses.

FAQ

Is there a technique which has better outcomes?

No technique is clearly superior in terms of long-term cosmetic outcomes or pain relief, as confirmed by multiple studies and a systematic review by Dean et al which found:

- Trephination (by any method) is just as effective as nail removal + repair for haematomas without nail margin disruption.

- Only one study (Roser and Gellman, 1999) directly compared the two and found no cosmetic difference, with zero infections in both groups.

What is the success rate of various trephination options?

Success isn’t always defined the same across studies, but generally means relief of pain and normal nail growth.

- Trephination (needle or hot tool):

- Near 100% relief of pain when performed within ~48 hours.

- Cosmetic outcomes are “generally good” — abnormal nail growth was 7% in Farrington’s early study.

- Infection rates: low, around 4.1–4.2% across multiple studies.

- No serious complications reported in observational or prospective series.

- Nail removal + bed repair:

- Similarly good cosmetic outcomes.

- However, higher invasiveness and cost with no proven benefit unless nail margin is disrupted or fracture is open.

Is there a measure of the increased cost of nail removal?

- Yes — Roser and Gellman (1999) demonstrated that “Nail removal and repair cost more than 4 times as much” as trephination alone.

- Unfortunately, exact dollar figures aren’t given, but the cost multiplier is significant, especially given equivalent outcomes.

- This makes routine nail removal hard to justify in the absence of nail margin disruption or open fracture.

Is there a benefit to multiple hole trephination?

No studies directly compare single vs multiple trephination holes in terms of outcomes, but clinical consensus suggests:

- Multiple holes may help if the haematoma is large (>50%) and covers multiple quadrants of the nail. However, one hole is often sufficient if the blood expresses well.

- Making additional holes can:

- Allow faster decompression

- Minimise need for repeat drainage

- Risk slightly more pain or nail damage if done poorly

Historical Context

- 1964 – Farrington publishes one of the earliest prospective studies of subungual haematoma management, comparing trephination methods.

- 1987 – Simon & Wolgin report a high rate of associated nail bed lacerations in large haematomas, influencing trends toward more aggressive nail bed exploration.

- 1991 – Seaberg et al. demonstrate good outcomes using trephination alone, even in cases with associated fractures.

- 1999 – Roser and Gellman provide the first direct comparison between nail trephination and full nail removal with bed repair in children. They find no cosmetic difference, but costs are 4x higher in the nail removal group.

- 2008 – Bonisteel promotes a safer, controlled manual drilling technique using a 23G needle, improving on hot wire risks.

- 2022 – Blereau et al. confirm 41.5% ignition rate when using electrocautery on acrylic nails, affirming caution in this population.

- 2023 – Akella et al. reaffirm the efficacy of trephination in a case series, noting full pain relief and no complications at follow-up.

References

FOAMed references

- Guthrie K. The Half Moon Nail. LITFL

Journal articles

- Farrington GH. Subungual haematoma—an evaluation of treatment. Br Med J. 1964 Mar 21; 1(5385): 742-4.

- Grisafi PJ, Lombardi CM, Sciarrino AL, Rainer GF, Buffone WF. Three select subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis, subungual osteochondroma, and subungual hematoma. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1989 Apr;6(2):355-64.

- Fountain JA. Recognition of subungual hematoma as an imitator of subungual melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990 Oct;23(4 Pt 1):773-4

- Meek S, White M. Subungual haematomas: is simple trephining enough? J Accid Emerg Med. 1998 Jul;15(4):269-71.

- Roser SE, Gellman H. Comparison of nail bed repair versus nail trephination for subungual hematomas in children. J Hand Surg Am. 1999 Nov;24(6):1166-70.

- Bonisteel PS. Practice tips. Trephining subungual hematomas. Can Fam Physician. 2008 May;54(5):693.

- Dean B, Becker G, Little C. The management of the acute traumatic subungual haematoma: a systematic review. Hand Surg. 2012;17(1):151-4.

- Blereau C, Radloff S, Grisham J. Up in Flames: The Safety of Electrocautery Trephination of Subungual Hematomas with Acrylic Nails. West J Emerg Med. 2022 Feb 23;23(2):183-185

- James V, Heng TYJ, Yap QV, Ganapathy S. Epidemiology and Outcome of Nailbed Injuries Managed in Children’s Emergency Department: A 10-Year Single-Center Experience. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2022 Feb 1;38(2):e776-e783

- Akella A, Daniel AR, Gould MB, Mangal R, Ganti L. Subungual Hematoma. Cureus. 2023 Nov 17;15(11):e48952

Emergency Procedures

BSc MD University of Western Australia. Interested in all things critical care and completing side quests along the way

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |