Teaching Practical Skills with SETT UP

There’s no body cavity that cannot be reached with a #14 needle and a good strong arm.

Samuel Shem, The House of God

Those of us in the medical field are no strangers to the sometimes-unfortunate truth of the above quotation. (If you’re a stranger to the quotation itself then please read the book; it almost counts as CPD…) Complications whilst undertaking practical procedures are inevitable but we do our utmost to minimise them for the good of our patients. Critical analysis and reflection on one’s own practice, and particularly on the unexpected complications therein, remain the bedrock of self-improvement. However, we can also work to minimise the complications experienced by others through effective teaching; it is possible that having taught a procedure to a more junior colleague, you may be the only person to ever directly supervise them whilst they undertake that procedure. It stands to reason that every opportunity should be taken to optimise this contact time.

It is vital that our practice remains current as new information supersedes old in order that we may provide the best possible care to our patients. The entire #FOAMed world, including the very site that this post sits within, has been created around this ideal. However the old adage of “See one, do one, teach one” when it comes to practical skills and procedures has remained enshrined within our collective consciousness for far too long. (One of my colleagues has expanded this adage to “See one, do one, teach one, DOPS one” but that’s a topic for another blog post…)

There are better ways. George and Doto (2001) presented a five-stage approach to teaching practical skills with a basis in pedagogic theory. This approach will be familiar to many readers, if not by name then by its use on life support courses (sometimes fondly known as “alphabet courses”: ALS, ATLS, APLS, PHTLS etc.) around the world. The following information is presented (with some amendments for brevity) as it appeared in the original paper:

Five-stage approach

- Conceptualisation – the learner must understand why it’s done, when it’s done, when it’s not done, and the precautions involved.

- Visualisation – the learner must see the skill demonstrated in its entirety from the beginning to end so as to have a model of the performance expected.

- Verbalisation – the learner must hear a narration of the steps of the skill along with a second demonstration.

- Verbalisation – if the learner is able to narrate correctly the steps of the skill before demonstrating there is a greater likelihood that the learner will correctly perform the skill.

- Practice – the learner having seen the skill, heard a narration, and repeated the narration, now performs the skill.

George and Doto also advocated immediate correction of errors and positive reinforcement to “cement correct performance.” The learner will (hopefully) go on to develop skill mastery and subsequent autonomy.

The above technique has shown itself to be safe and effective in countless learning encounters and lends itself well to a simulated environment. However, it is far less useful when delivering ad-hoc teaching in a clinical environment; I’m yet to meet the patient that was willing to have their shoulder re-dislocated so a trainee could progress through stage three, let alone stages four and five!

Additionally, the rapid turnover of staff in many emergency departments and assessment units means that you may only meet your learner (be it an undergraduate or a more senior trainee) on a handful of occasions, and you may therefore be unaware of where within the process of skill acquisition they are currently situated. This has the potential to lead to either an over-protective approach with an experienced trainee or a dangerous paucity of supervision for the less experienced.

It would seem desirable to draw upon the established techniques for skills teaching whilst designing a system that is better suited to the shop floor working environment. The following system is based upon George and Doto’s five-stage approach and is one I have found useful, both in my own practice and when “training the trainer”:

S etting the scene

E stablish prior experience

T alk through the procedure (led by the learner)

T ips and tricks (provided by the instructor)

U ndertake procedure (with direct supervision)

P ost-procedure feedback

Setting the scene – it may be that the learner who is to undertake the procedure has had no involvement with the patient in question. Therefore, discuss the clinical situation with the learner. Make sure they are happy with the indications, contraindications and important considerations when undertaking the procedure. (Aside: I would encourage everyone reading to see every practical procedure as a learning opportunity for someone. Manipulating a distal radial fracture or putting in a chest drain may be commonplace for you but there’s probably a junior trainee less than 20 yards away who would value the opportunity. Make practical procedures into learning events whenever possible.)

Establish prior experience – you need to find out how many times the learner has observed or performed the procedure before. This is a decision point; are you going to undertake the procedure yourself and have the learner watch? Watching is probably most appropriate if the learner has never even seen the procedure before. In this situation you can perform the procedure whilst talking through the stages involved (the first “verbalisation” stage of George and Doto’s approach) and therefore the learner will be better placed to progress their skills the next time an opportunity to undertake the procedure presents itself. Alternatively, the learner may have adequate experience to undertake the procedure themselves.

Talk through the procedure – this process is led by the learner and is akin to the second “verbalisation” phase described earlier. This provides an opportunity for the instructor to assess the learner’s understanding and clarify key points such as anatomical landmarks or drug doses. It also forces the learner to break the procedure down in a step-wise fashion.

Tips and tricks – These will clearly vary dependent upon the skill being performed; perhaps “make sure you keep the skin taught or the vein is likely to move” for phlebotomy or “try not to go in at too sharp an angle with the needle or it will be difficult to pass the drain later” for Seldinger chest drains. Many of us will have had “ah ha!” moments when learning new procedures and finally overcoming a recurrent barrier to success; this is your opportunity to short-cut that stage for your learner.

Undertake the procedure – the level of supervision required will have been determined during the preceding stages. During the learner’s first time performing the procedure you may be at their side, gloves on, ready to assist. The more experienced trainee may merely desire your presence in the room; in that case, you can make yourself useful by chatting to the patient and helping them to relax! You should of course intervene if patient safety is (or may be) compromised at any time.

Post-procedure feedback – this may be as simple as “Well done! The next time you’re on your own.” However, immediate feedback on any errors is likely to improve retention of information and reduce the potential for developing bad habits. If things did not go well, consider agreeing a development plan with the learner: “Come and get me next time you have another one to do and we’ll go through it again” or “lets find another patient that needs a cannula and have another go.”

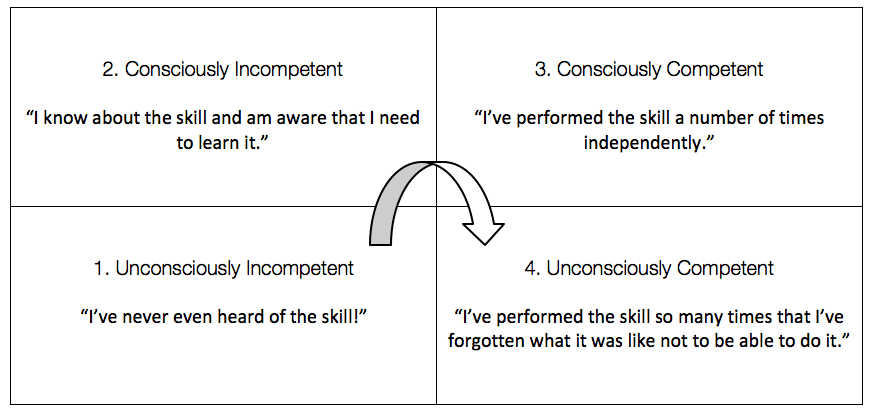

Much of the above is merely formalising what I’m sure many readers probably do already, in one format or another. However, this in itself is key to teaching any practical skill (including the skill of how to teach a skill… now I feel like I’m a character from “Inception”…) Breaking down any skill into its component elements and dealing with each in turn is vital when dealing with a new procedure but is surprisingly difficult when attempted for the first time; particularly when you may have been performing that procedure for many years. Counter-intuitively, taking yourself backwards around the matrix (see below) from unconsciously competent to consciously competent makes it easier to break the skill down into stages and understand where the learner may be getting stuck. (It has been argued that this process is not moving backwards on the matrix but actually moving forwards to a 5th stage, “Reflective Competence.” However, this doesn’t fit so easily into a table… Perhaps the “Pentagon of Reflective Competence”?)

So next time you have a practical procedure to do on the shop floor, turn it into a learning event, break it down into stages and SETT UP for success! (Sorry, I couldn’t help myself.)

…a step up from the traditional teaching methods:

Eyes first and most; hands, next and least and tongue not at all

References

- George, JH and Doto, FX. A Simple Five-step Method for Teaching Clinical Skills. Fam Med. 2001; 33(8):577-8 [PMID 11573712]

Other thoughts…

SMILE 2

Better Healthcare

EM doctor, in-situ sim fan, junior researcher, music lover, budding photographer. Eternally itchy feet. CESR Trainee and Teaching Fellow, Royal Derby Hospital | @andrewtabner |