The men who stare at goats (and big boar)

aka Tropical Travel Trouble 014

Peer Reviewed by Dr Jennifer Ho – Infectious disease specialist in Queensland.

To your delight you are working the same week as the annual ‘King and Queen Central Queensland Big Boar competition’. Mr AJ, the 45 yr old winner of the competition (with a boar tipping the scales at 138.9kg) presents to your department with a flu-like illness with symptoms including fever, fatigue, arthralgia and anorexia. He has been feeling unwell for a few weeks and only presented to ED because his back pain was making it difficult for him to walk. He assumed he had twinged it whilst man-handling the 138.9kg beast. Incidentally, he is also describing increasing troublesome thoughts of hopelessness and dismay about not beating his personal record of 152kg.

Q1. What is the differential diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

This man presents with a very non-specific constellation of symptoms that could mimic any number of other diseases. The key to clinching the diagnosis here is failing to consider Brucella infection in a patient with a history that suggests a possible source for the infection (feral pig hunter).

Q fever presents in a similar manner to brucellosis and its risk factors may coexist with brucellosis risk factors. One important although not totally distinguishing feature is acute Q fever usually has an abrupt onset while brucellosis usually has a gradual onset. That said chronic Q fever can present the same so… probably best to test for both. Other diseases that causes recurrent fevers include malaria, typhoid and TB.

Q2. What is brucellosis and how is it transmitted?

Answer and interpretation

Brucellosis is a zoonotic infection caused by the aerobic gram negative intracellular coccobacilli Brucella. There are numerous species however the most important species from a human health perspective are:

- B. suis (Found in pigs, only species present in Australia and a common problem in the USA).

- B. melitensis (normally resides in sheep, goats and occasionally camels. Found in the Mediterranean, Middle East and Central and South America. )

- B. abortus (usually seen in cattle in Africa, the Indian subcontinent and temperate zones)

- B. canis (one for the dogs, this rarely infects humans).

B. suis is present in up to 20% of feral pigs in Australia. It is not present in New Zealand feral pigs. Hunters may become infected following contact with feral pig blood via skin breaks/ exposed mucous membranes during the slaughter process. Dogs may become infected after consuming infected raw feral pig meat. Dogs may infect humans predominantly around the time of whelping (breeders) and during surgical procedures e.g. de-sexing operations (veterinarians). Brucellosis may also be contracted via inhalation of contaminated dust or aerosols. Human-human transmission is rare although can occur through sexual contact, blood transfusions, tissue transplantation, breastfeeding or congenital transmission. Laboratory transmission from infected specimens or culture isolates can also occur.

In countries where B. melitensis, B. abortus and B. canis are present in animals, transmission occurs through ingestion of unpasteurised dairy products (hence Malta fever – more on that later), or through direct contact with animal tissues (especially aborted fetuses), blood and urine via skin abrasions and mucous membranes. It is not contracted my eating contaminated meat (unless you are eating it raw).

The incubation period is 5-60 days as the organisms are sneaky and live intracellularly hiding in the reticuloendothelial system.

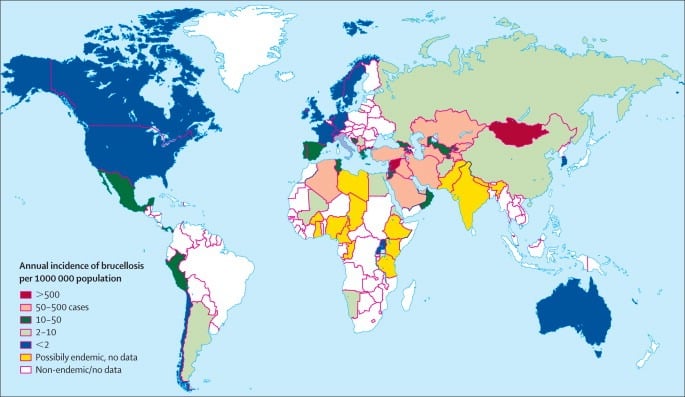

Q3. How common is Brucellosis?

Answer and interpretation

Between 1991 and 2016, an average of 30 cases were diagnosed annually in Australia (1.6 cases per 1,000,000 population). Eighty percent of these cases occurred in Queensland (6.7 cases per 1,000,000 population).

New Zealand has only had 15 cases of (internationally acquired) brucellosis notified since 1996. B. abortus was eradicated from New Zealand in 1996 and at present the feral pigs do not carry B. suis.

In the US, fewer than 100 cases per year are reported to the Centre for Disease Control.

Internationally, Brucellosis causes 500,000 infections per year worldwide.

Q4. How does brucellosis present clinically?

Answer and interpretation

Usually brucellosis presents in a gradual fashion although abrupt onset is also possible. It is a systemic infection that may involve any organ system (i.e. everything -itis, arthritis, pericarditis, hepatitis, meningitis – you get the picture).

Common symptoms include:

- Fever and sweats (80-100% cases). Classically recurrent bouts of prolonged fevers that is left untreated can go on for weeks, then resolve only to start up again.

- Half of all cases have musculoskeletal problems. Think of a child with a fever and a painful hip or knee. While septic joints and rheumatic fever are reasonable differentials, in the right context it could be Brucellosis.

- Fatigue, anorexia, weakness (>90% cases)

- Headache

- GI symptoms (50%)

- Depression in 30%

Clinical signs:

- Look unwell, lethargic but not toxic

- Febrile but the temperature returns to normal during a 24hr cycle

- 10% have cervical lymphadenopathy

- 25% have splenomegaly

- Swollen joint(s)

- Tender vertebrae on movement or sacroiliac joints.

In an endemic area, anyone who presents with recurrent fever, difficulty walking and profuse night sweats needs to have Brucellosis excluded. As listed above and as noted in our patient, depression, anorexia and lethargy while they seem non specific can be classic in patients with Brucellosis, its just often insidious and needs to be asked about.

Complications may include:

- Osteoarticular – sacroilitiis in 30-70% cases

- Genitourinary – epididymo-orchitis

- Spontaneous abortion when associated with infection in 1st or 2nd trimester

- Neurobrucellosis – chronic lymphocytic meningitis or a meningoencephalitis.

- Hepatosplenic brucellomas

- Cardiovascular –myocarditis, pericarditis and endocarditis (often the main cause of death)

- Respiratory – pleural adhesions, bronchopneumonia and chronic cough.

- Endophthalmitis

- Bleeding – epistaxis from thrombocytopenia is the most common manifestation but cases of haematemesis and malaena have been reported.

The overall mortality rate is 2% usually from endocarditis. Relapse sometimes occurs in the first year in up to 10% of patients despite appropriate antibiotics. B melitensis may cause chronic disease that can resemble chronic fatigue syndrome (fatigue, depression. myalgia).

Q5. How do you diagnose acute Brucellosis?

Answer and interpretation

Preliminary bloods: You may note the following on basic bloods

- Low white blood cells – lymphopenia

- Low platelets and occasionally haemoglobin

- Raised alkaline phosphatase and transaminases

Serology:

The most common serological methods used are the serum agglutination test (SAT) or Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

SAT:

If someone is infected with Brucellosis they will produce antibodies to that specific species. The SAT kits have specific Brucella antigens and will causes an agglutination reaction if the patient is positive. How to interpret the results: like syphilis results, the aim here is to dilute the blood from say 1:20 to 1:160 to see if there is a reaction. Someone who is in an endemic area may be positive from background and prior exposure if we didn’t dilute their blood, but if they had high bacterial loads even in the most dilute form their blood would cause a reaction. Hence in a non-endemic area a cut off can be 1:80 whereas in an endemic area the lab maybe set at 1:320. There is also another phenomenon that can occur called the ‘prozone phenomenon’ or ‘hook effect‘. If you imagine you have the antigen and your body is producing lots of antibodies there is a chance in an undiluted blood sample that there is no spare antibodies to react to your SAT test. Its only when diluting the blood you wash out spare antigens and are hopefully left with some antibodies to react to your test. Most labs only dilute down to 1:160 but sometimes with Brucellosis the test won’t be positive until more dilute concentrations of 1:320 or 1:640, this is called the prozone phenomenon.

- IgG titre – A fourfold increase between acute and convalescent testing (obtained ≥ 2 weeks apart) is diagnostic for Brucellosis but obviously not pragmatic to wait for prior to commencing therapy.

- IgM may be detectable and differentiated from IgG at time of diagnosis however cannot be relied on due to cross reactivity with other infectious agents.

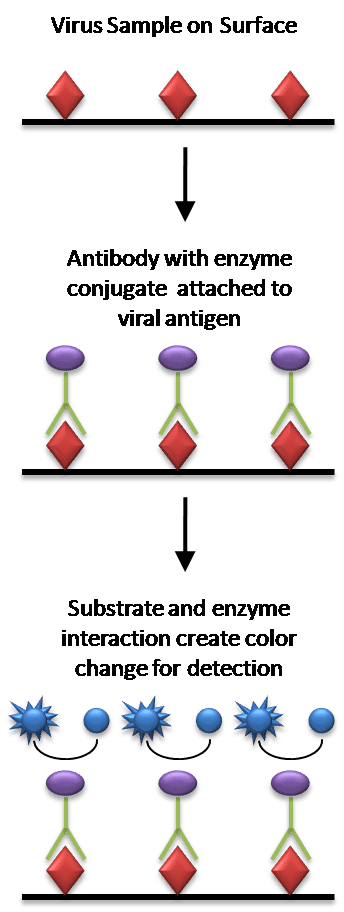

ELISA:

Antigens from the sample are attached to a surface. Then, a matching antibody is applied over the surface so it can bind the antigen. This antibody is linked to an enzyme and then any unbound antibodies are removed. In the final step, a substance containing the enzyme’s substrate is added. If there was binding the subsequent reaction produces a detectable signal, most commonly a color change.

Blood Cultures:

Blood cultures are important as they help to exclude other diagnoses and if positive for Brucella, allow speciation to determine where the organism was contracted. This is important from a public health perspective.

Most cultures become positive within 7 days but some take as long as 21 days (recommend to run for 6 weeks if only using basic equipment). It is also important to remember that blood cultures are not 100% sensitive and some studies have the positivity rate as low as 30%. If you suspect Brucellosis it is important to inform the laboratory so they can incubate the cultures for longer but also due to the risk of aerosol spread in the lab.

PCR:

Both genus-specific and species-specific Brucella PCR assays are available from public health reference laboratories. They are most helpful when used on culture negative tissues and for organism speciation.

Other cultures:

- Bone marrow can be more sensitive than blood cultures especially in a patient with pyrexia of unknown origin who has already received antibiotics.

- Synovial fluid

- CSF

- Lymph nodes or any other abnormal tissues.

Q6. How do you treat Brucellosis?

Answer and interpretation

Depending on your practise three questions need to be asked:

- Is the disease acute (<1 month) or relapsing or chronic (>6 months)?

- Is there focal disease of bone or joints?

- Has TB definitely been excluded?

Acute and non-focal:

According to the WHO, for adults or children >8 years of age, it requires dual therapy with oral doxycycline for six weeks and IV gentamicin for 7 to 10 days (as 7 days has been proven to fail in some studies). Due to the potential nephro-, oto- and vestibular toxicity patients should be admitted to hospital for specialist therapeutic drug monitoring for the duration of their gentamicin therapy.

Rifampicin is a suitable alternative for gentamicin in cases where it is contra-indicated however it requires a six-week course. DO NOT use rifampicin or streptomycin if TB is a possibility or has not been excluded.

Regimens for treatment of Brucellosis (in absence of focal disease due to spondylitis, neurobrucellosis, or endocarditis)

(Rifampicin and Gentamicin are dosed at ideal body weight.)

| Regimen | Dosing | |

| Nonpregnant adults and children 8yrs and older | Doxycycline + Gentamicin | Doxycycline: 100mg orally BID for 6 weeks (2 mg/kg for children max dose 100mg) Gentamicin: 5mg/kg/day IV for 7 to 10 days (usually 7.5mg/kg in children) follow local guidelines for daily dosing. |

| Doxycycline + Rifampicin | Doxycycline: 100mg orally BID for 6 weeks (2 mg/kg for children max dose 100mg) Rifampicin: 600 to 900 mg orally once a day for 6 weeks (15 mg/kg for children– max 600mg) | |

| Children <8 years old | TMP – SMX + Rifampicin | TMP 5 mg/kg (max 160 mg) and SMX 25 mg/kg (max 800mg) twice a day for 6 weeks Rifampicin 15 mg/kg (max 600mg) once a day for 6 weeks |

| TMP – SMX + Gentamicin | TMP 5 mg/kg (max 160 mg) and SMX 25 mg/kg (max 800mg) twice a day for 6 weeks Gentamicin 7.5mg/kg/day IV for 7 to 10 days (follow local guidelines for daily dosing) | |

| Pregnant women (seek expert consultation in those women 36 weeks or greater as TMP/SMX can cause neonatal kernicterus and some advocate for rifampicin only until delivery) | TMP – SMX +Rifampicin | TMP-SMX: 1 double strength tablet (DS = 160mg TMP) orally twice daily for 6 weeks + folate Rifampicin: 600 to 900 mg orally once daily for 6 weeks. |

Focal or Chronic Disease:

Requires 3 months of treatment of the tetracycline beyond the initial 1-2 week load of gentamicin. See tables below for dosing regimens.

Children and pregnancy:

Co-trimoxazole with folate supplementation offers a great alternative to children and pregnant patients who need to avoid tetracyclines. This is less ideal in the first trimester but considered safe if adequate folate supplements are given. Brucellosis however, does cause spontaneous miscarriage so the benefits of co-trimoxazole outweighs the risks.

What about triple therapy?

Triple combination of doxycycline, rifampicin and gentamicin is superior to double therapy and should be used in all infections with complications such as severe spondylitis, endocarditis or meningitis.

Regimens for treatment of Brucella spondylitis and endocarditis (seek surgical consult if endocarditis and potentially extend treatment for 4-6 months).

| Regimen | Dosing | |

| Nonpregnant adults and children 8yrs and older | Doxycycline + Rifampicin + Gentamicin | Doxycycline: 100mg orally BID for 12 weeks (2 mg/kg for children max dose 100mg) Rifampicin: 600 to 900mg once daily for 12 weeks (15 mg/kg in children – max 600mg) Gentamicin: 5mg/kg/day IV for 7 to 14 days (usually 7.5mg/kg in children) follow local guidelines for daily dosing. Extend therapy to 4 weeks if treating endocarditis. |

| Children less than 8 years | TMP – SMX + Rifampicin + Gentamicin | TMP 5 mg/kg (max 160 mg) and SMX 25 mg/kg (max 800mg) twice a day for 12 weeks Rifampicin: 15 mg/kg (max 600mg) once daily for 12 weeks Gentamicin: 7.5mg/kg/day IV for 7 to 14 days (follow local guidelines for daily dosing. Extend therapy to 4 weeks if treating endocarditis. |

| Pregnant women (seek expert consultation in those women 36 weeks or greater as TMP/SMX can cause neonatal kernicterus and some advocate for rifampicin and ceftriaxone until delivery) | Ceftriaxone + Rifampicin + TMP-SMX | Ceftriaxone: 2g IV once daily for 4 to 6 weeks. Rifampicin: 600 to 900 mg orally once daily for 12 weeks. TMP-SMX: 1 double strength tablet (DS = 160mg TMP) orally twice daily for 12 weeks + folate |

Treatment for Neurobrucellosis – limited studies but at least 3 months of treatment is required and with some patients requiring 4-6 months.

| Regimen | Dosing | |

| Nonpregnant adults and children 8yrs and older | Doxycycline + Rifampicin + Ceftriaxone | Doxycycline: 100mg orally BID for 12 weeks (2 mg/kg for children max dose 100mg) Rifampicin: 600 to 900mg once daily for 12 weeks (15 mg/kg in children – max 600mg) Ceftriaxone: 2g IV daily for 4 to 6 weeks (25-50mg/kg in children) |

| Children less than 8 years | TMP – SMX + Rifampicin + Ceftriaxone | TMP 5 mg/kg (max 160 mg) and SMX 25 mg/kg (max 800mg) twice a day for 12 weeks. Rifampicin: 15 mg/kg (max 600mg) once daily for 12 weeks Ceftriaxone: 25 – 50mg/kg (max 2g) once daily for 4-6 weeks |

| Pregnant women (seek expert consultation in those women 36 weeks or greater as TMP/SMX can cause neonatal kernicterus and some advocate for rifampicin and ceftriaxone until delivery) | Ceftriaxone + Rifampicin + TMP-SMX | Ceftriaxone: 2g IV once daily for 4 to 6 weeks. Rifampicin: 600 to 900 mg orally once daily for 12 weeks. TMP-SMX: 1 double strength tablet (DS = 160mg TMP) orally twice daily for 12 weeks + folate |

Q7. Can you prevent Brucellosis?

Answer and interpretation

There are no vaccines for humans or dogs however there are several licensed live Brucella vaccines available for use on livestock. This vaccination campaign resulted in the in the eradication of bovine Brucella in Australia and New Zealand in the mid-1990s. Other options include ‘test and slaughter’ so if one animal tests positive the whole heard are slaughtered.

Those at risk of contracting Brucella should take care when handling potential infected sources e.g. pig hunters should wear protective clothing, cover abrasions and try and prevent their dogs from consuming raw pig meat.

Travellers to endemic areas should avoid consuming unpasteurised dairy products and having unprotected contact with animal tissues, blood and other body fluids.

Case Resolution:

Case Outcome

You strongly suspected Mr AJ had a case of brucellosis based on his numerous close encounters with feral pigs. You referred him to your friendly infectious diseases team who admitted him and commenced him on doxycycline and gentamicin once his cultures were positive for gram negative coccobacilli at 24 hours incubation. He made an uneventful recovery and as soon as he was discharged took his pig dog ‘Peppa’ off to the vet for a work up.

Resources:

Historical controversies – Sir David Bruce and the men who stare at goats?

In 1886, Sir David Bruce (1855-1931) served in Malta while there was an outbreak Malta fever and led the Malta Fever Commission (MFC). One year later he identified the organism that caused the fever as a bacterium Micrococcus melitensis (later renamed Brucella melitensis). In 1893, Britain’s greatest peacetime naval disaster, the loss of the battle ship HMS Victoria was attributed to Malta fever. The natural reservoir of Malta fever, a cure or vaccine was a national priority. It took a further 13 years before the discovery in 1905 to realise goats were the animal reservoir. Who discovered that goats were to blame remains a historical contention which I shall endeavour to explain below but you decide whose genius it was.

Lets set the scene as all four men below will claim credit (well Zammit less so). Sir David Bruce is chair of the MFC and all correspondence and findings go through him. Sir William Horrocks is a key member of the FRC and is largely the superior on the ground in Malta to Themistocles Zammit, a Maltese doctor and Staff Surgeon Ernest Shaw. Horrocks and Shaw worked closely together on the top floor of the laboratory while Zammit worked downstairs connected by a ‘speaking tube’ – its purpose is unknown. It is also important to point out contextually, that in 1897 Ronald Ross had made the important discovery that malaria was transmitted by mosquitoes so much of the MFCs work involved trying to prove mosquitoes carried Brucellosis.

In 1904 Zammit spent a journey to Chadwick lakes to investigate some cases of malaria. In the carriage was fellow medical officer Caruana Scicluna who potentially told Zammit about a case of a family becoming ill after drinking goat’s milk. In the summer of 1904 Zammit was running low on monkeys so started experimenting on the local goats. He fed them M. melitensis and recored their symptoms.

Zammit is also trying to infect a goat by feeding it on Micrococcus Melitensis; if he succeeds we intend to repeat the experiment of feeding a monkey on its milk.

Horrocks to Bruce

Zammit fed his white goat on agar cultures of M. melitensis on 18th of September and 3rd of December 1904. The goat showed positive agglutination on 3rd and 23rd of December and again on the 29th of April 1905. He repeated his experiment and wrote that:

These two experiments led me to belief that goats are susceptible to Malta fever, and that the disease may be spread to human beings by goats.

Zammit to Bruce May 1905

Bruce then directed the MFC to investigate both mosquitoes and goats. On the day Bruce left Malta for London June 12, 1905, Zammit bought six healthy goats and took them to the laboratory in Lazaretto. Prior to any experiments he found 5 our of the 6 were infected.

Zammit bought six more for experimental purposes and on examining their blood before using them, found a certain number of them agglutinated. He brought these upstairs to be confirmed; Horrocks and I each examined them and found it was so. Zammit says at Caruana Scicluna’s suggestion he brought milk from each of these for examination.

Shaw to Bruce, July 5, 1905

It was agreed Horrocks would examine milk and Zammit the blood.

Of the six goats I had bought for the lazaretto I found that not less than five reacted to M.M. I informed Horrocks of the fact and passed him some milk for examination. He found the coccus in this milk and I found it abundant in the blood of the same goat.

Zammit to Bruce June 30, 1905

Shaw, on re-examining his goats, found the micrococcus in their milk and blood. Perhaps increasingly frustrated that his work ws being overshadowed and perhaps not voicing a similar finding 12 months ago wrote to the Royal Society in Aug 1905 to claim priority in the discovery. He also sent a formal paper on Nov 1905 for publication in the Commission Reports staking prescience:

To determine experimentally to what degree goats, which are so numerous in Malta, are susceptible to Malta fever, I determined, in July, 1904, to inject Micrococcus melitensis subcutaneously into these animals.

Shaw Nov 1905

Bruce was surprised that Shaw hadn’t mentioned this discovery before when he was in Malta in May, when they were discussing Zammit’s experiments. Horrocks replied to Bruce’s questions:

Shaw certainly injected goats and produced a serum, but that is far from proving ‘goats are susceptible to Malta fever’… At the end of the summer, 1904, he told me he did not want his goats any longer, so they were sent out to field.

Horrocks to Bruce Dec 11, 1905

Goats’ milk was banned by the military authorities in May, 1906, thereby virtually eradicating Malta fever from the garrison. Caruana Scicluna (now Chief Government Medical Officer) and Zammit tried to lead a public campaign but many civilians were a strong advocate for their unpasteurised products. In fact to this day there are still levels of Brucellosis in Maltese goats. In 1995, 200 people became infected from some unpasteurised goats cheese on the Island of Malta.

So who received credit in the end… Bruce, largely through anonymity techniques. He wrote a long editorial in March 1906 issue of J R Army Med Corps which he states

It is unnecessary to describe the various steps which led up to the important discovery that roughly 50% of the goats in Malta are affected by this disease, and that 10% are excreting the micrococcus in their milk

Bruce gave many talks on the subject and wrote in textbooks omitting names but merely referring to the ‘work from the Commission in Malta’. In later years Bruce would argue the Commission as a whole should gain credit for the overall work not individuals working on the separate projects, this seems laudable but on the other hand this didn’t stop him naming individuals in negative circumstances when it suited. Or maybe he was just exasperated by the Shaw / Horrocks’ feud.

See photo below, Zammit is in the top left and Bruce looking very stern is in the middle. Perhaps grumpy he could no longer drink some unpasteurised goats milk?

References

- Vassallo DJ. The saga of brucellosis: controversy over credit for linking Malta fever with goats’ milk. Lancet. 1996 Sep 21;348(9030):804-8

- Wyatt HV. How Themistocles Zammit found Malta Fever (brucellosis) to be transmitted by the milk of goats. J R Soc Med. 2005;98(10):451-454

- Pappas G et al. The new global map of human brucellosis. The Lancet Infectious Disease. 2006;6(2):91-99

- Dean AS et al. Clinical Manifestations of Human Brucellosis: A Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012

- Beeching N and Gill G. Lecture Notes – Tropical Medicine. 7e Wiley Blackwell 2014.

- Eddleston, Davidson, Brent, Wilkinson. Oxford Handbook of Tropical Medicine. Oxford Medical Handbooks. 4e 2014

- Matthews PC. Tropical Medicine Notebook. Oxford University Press, 2017

- Kloss B. Graphic Guide to Infectious Disease. 1e, 2018

- UpToDate: Brucellosis: Treatment and prevention. Accessed Jan 20th 2021

CLINICAL CASES

Tropical Travel Trouble

MBChB, MEmergHlth, FACEM. Kiwi emergency physician working in tropical Far North Queensland. Work interests include little people and making things happen faster and better. Outside work I'm a lifetime wonderer, devoted festival attendee, recurrent toddler wrangler and occasional body builder

Dr Neil Long BMBS FACEM FRCEM FRCPC. Emergency Physician at Kelowna hospital, British Columbia. Loves the misery of alpine climbing and working in austere environments (namely tertiary trauma centres). Supporter of FOAMed, lifelong education and trying to find that elusive peak performance.