Trauma! Traumatic Brain Injury

aka Trauma Tribulation 015

A 67 year old man tripped down some steps at a pub and hit his head. He is brought to the ED by ambulance. He is GCS 10 (E2V3M5), with PERL and no focal neurological deficits. He has a haematoma on his right temporal region.

Questions

Q1. Which patients are at highest risk of morbidity and mortality from traumatic brain injury?

Answer and interpretation

The following groups of patients are at particular risk:

- The elderly (risk of falls, cerebral atrophy)

- Infants (large head size, compressible skull, risk of non-accidental injury)

- Patients with a bleeding diathesis (e.g. on warfarin)

- Chronic alcoholics (at risk of falls and assaults, cerebral atrophy, coagulopathy due to chronic liver disease)

Q2. How is the severity of traumatic brain injury classified on initial assessment?

Answer and interpretation

The simplest way to categorise severity of TBI on initial assessment is by using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS):

- Minor = GCS 13-15

- Moderate = GCS 9-12

- Severe = GCS <8

Based on GCS, this patient has a moderate severity TBI.

- Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974 Jul 13;2(7872):81-4. [PMID 4136544]

Q3. What is the difference between primary and secondary brain injury?

Answer and interpretation

Primary injury occurs at the time of the initial traumatic event, and may be focal or diffuse. Focal injuries include hematomas, contusions and lacerations resulting from blunt or penetrating trauma. Diffuse injuries typically result from acceleration-deceleration forces and affect the whole brain resulting in axonal shearing or concussion.

Secondary injury is potentially preventable and reversible, and occurs after the time injury. Mechanisms of injury include oedema, hypoxia, hypotension, and metabolic disturbance.Once the primary brain injury has been recognized, the main objective of the management of acute traumatic brain injury is the prevention of secondary brain injury.

Q4. What is the Monro-Kellie doctrine and what are the implications for the management of traumatic brain injury?

Answer and interpretation

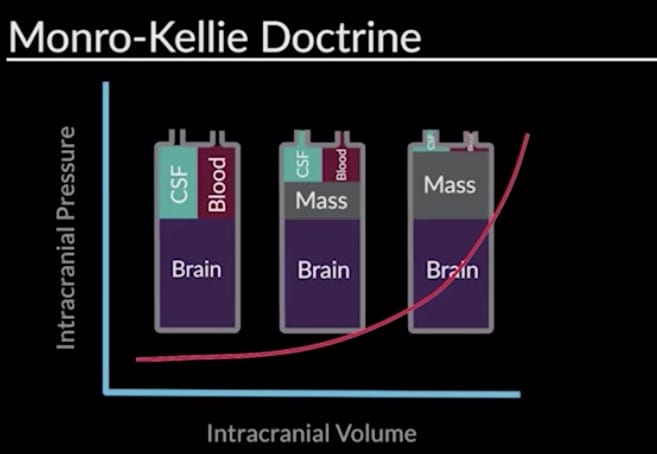

The Monro-Kellie doctrine holds that the brain lies within a rigid box (the cranium). In addition to brain, within the rigid box there is blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). As a result, expansion of the volume of any of the components must be offset by an equal decrease in volume of the others or intracranial pressure will increase.

The compensatory capacity within the non-compliant cranium is limited. The capacity for CSF to displace into the spinal theca and into the venous system via arachnoid granules, and intracranial blood to redistribute peripherally is easily overcome. This usually occurs with mass lesions of about 100 to 120 mls, and when it does intracranial pressure increases linearly.

The implication for management of traumatic brain injury is that space is at a premium, and aggressive treatment to control the volume of intracranial contents is essential to prevent raised intracranial pressure which can lead to compression of vital brain structures, impaired blood flow to the brain and ultimately death.

Andy Neill describes the main anatomical types of brain herniation in this video

Q5. What is cerebral perfusion pressure and how does raised intracranial pressure impair blood flow to the brain?

Answer and interpretation

Cerebral Perfusion Pressure = Mean Arterial Pressure – Intracranial Pressure

that is,

CPP = MAP − ICP

Blood, like any other fluid, tends to flow from high to low pressure. Hence raised intracranial pressure decreases the pressure gradient favouring blood flow to the brain. Hence, CPP is used as a surrogate marker of cerebral blood flow. It also follows that to maintain blood flow to the brain in the presence of raised intracranial pressure, and increased driving pressure (i.e. mean arterial pressure) is required.

Q6. How is the concept of cerebral autoregulation relevant to traumatic brain injury?

Answer and interpretation

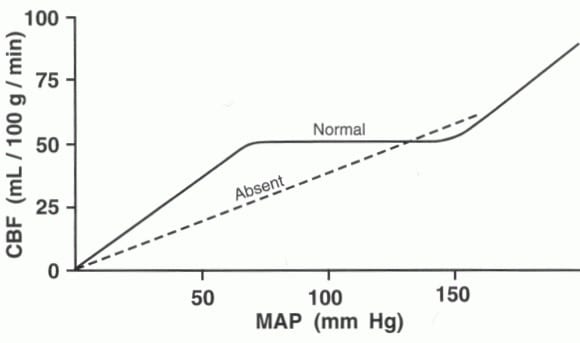

We saw in Q5 that because CPP is related to MAP, cerebral blood flow should increase with increased MAP. In this normal brain, this is not the case because of cerebral autoregulation. The normal brain uses compensatory mechanisms to preserve constant cerebral blood flow over a range of physiologically tolerable MAPs (60 to 150 mmHg). This is shown by the horizontal segment of the sigmoid curve shown below:

CBF will fall when the MAP is below the range of autoregulation, and rise when the MAP is above the range of autoregulation.

The injured brain is unable to perform cerebral autoregulation. As a result CBF is directly dependent on MAP, resulting in the dashed linear curve shown above. Thus optimize of MAP is critically important in the management of severe traumatic brain injury.Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg) doubles mortality in patients with severe TBI.

Q7. What are the common indications for a head CT in traumatic brain injury?

Answer and interpretation

Indications for a CT head following ‘significant’ blunt trauma to the head include:

- GCS <13

- GCS <15 post-injury

- Age >65 years

- Bleeding diathesis or on anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents

- Focal neurology

- Suspected open or depressed skull fracture

- Evidence of basal skull fracture

- Vomiting > 1 episode

- Retrograde amnesia >30 minutes

- Dangerous mechanism (e.g. pedestrian versus vehicle, fall >1m or 5 stairs, ejected from motor vehicle)

In practice, I use the Canadian CT Head Rules (available here at MDCalc) in combination with clinical judgment and considerations such as coagulopathy, GCS <13 and focal neurology as listed above. Of note, the Canadian CT Head Rules were designed to be used in GCS 13-15 patients with witnessed loss of consciousness, amnesia to the head injury event, or confusion.

The 3 major adult CT Clinical decision rules are summarised at Academic Life in Emergency Medicine in a handy ‘Paucis Verbis’ card: Head CT Decision Rules in Trauma

- Canadian CT Head Rules

- New Orleans Criteria

- National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS)-II

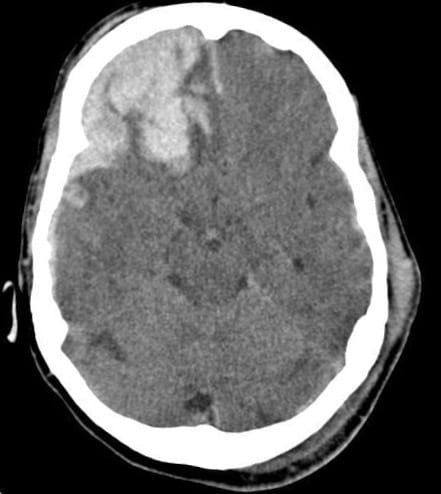

The patient has a CT scan, which shows this:

Q8. Describe what is shown?

Answer and interpretation

Left-sided extradural hemorrhage (the lenticular lesion adjacent to the skull)

Other findings:

- left-sided extracranial hematoma

- mild deviation of the falx suggesting early midline shift

- loss of the the usual sulcal appearance also suggests a ‘tight’ brain (raised intracranial pressure)

On returning to the trauma bay from the CT room he is now GCS7 (E1V2M4).

Q9. Describe your overall approach to the management of a patient with severe traumatic brain injury.

Answer and interpretation

Approach to severe TBI in the ED:

- Activate the trauma team and use a coordinated team-based approach in a dedicated trauma bay appropriately staffed and equipped for resuscitation.

- Remove the patient from a rigid spine board as soon as possible by transferring onto a trauma bed

- Primary survey and resuscitation (ABCDE approach)

- Airway maintenance with cervical spine immobilization

— intubate if GCS <8

— consider intubating patients with higher GCS if agitated, hypoxic or hypoventilating

— avoid nasopharyngeal airways due to the risk of intracranial passage

— maintain cervical spine precautions - Breathing and ventilation

— high flow oxygen 15L/min via a non-rebreather mask

— target PaCO2 35 +/- 2 mmHg (low-normal range) - Circulation with haemorrhage control

— target MAP of 70 mmHg to maintain adequate CPP; some advise MAP 80-90 mmHg to allow for variations during resuscitiation

— avoid permissive hypotension in trauma patients with significant head injuries - Disability (neurological evaluation)

— assess GCS, pupils and motor and sensory function in all limbs prior to sedation or intubation

— suspect critically raised intracranial pressure if: Cushing’s response (bradycardia, hypertension, apneas), fixed and dilated pupil(s), hemiparesis.

— treat suspect critically raised intracranial pressure: head up 30 degrees, remove neck constrictions, administer mannitol 0.25 to 1 g IV bolus or 3% hypertonic saline according to local guidelines, urgently liaise with neurosurgery and consider burrholes if transfer to neurosurgeon likely to take >2 hours.

— treat seizures and consider prophylactic anticonvulsants according to local guidelines. - Exposure and Environmental Control

— maintain T36-37; give antipyretics if T>38C

- Airway maintenance with cervical spine immobilization

- Adjuncts to Primary Survey and Resuscitation

— ECG and full non-invasive monitoring including temperature

— Obtain trauma series radiographs as needed (lateral cervical spine XR, chest XR, pelvic XR)

— Bedside ultrasound to identify other injuries and sources of haemorrhage (e.g. EFAST)

— Seek and treat coagulopathy

— Orogastric tube insertion if intubated

— Indwelling catheter insertion - Consider transfer

— Organize early transfer to a neurosurgical unit - Secondary survey

— Head-to-toe examination looking for other injuries - Adjuncts to Secondary Survey

— Organize CT head to define the nature of the traumatic brain injury - Continued post-resuscitation care and monitoring

— Remember FASTHUGS IN BED Please!

— Ensure adequate sedation and analgesia

— Avoid colloids and hypotonic solutions

— Targets: PaO2 >100 mmHg, PaCO2 35 mmHg, T 36-37C, MAP>70 mmHg (CPP 50-70 mmHg if ICP monitor is placed), glucose 6 – 10 mmol/L

— Neurosurgery to consider ICP monitor insertion - Definitive care and disposition

— Transfer to neurosurgical unit/ ICU for ongoing care

Q10. Anatomically, what are the different types of traumatic brain injury?

Answer and interpretation

Diffuse injuries

- These range from simple concussion with an excellent prognosis to diffuse axonal injury with associated grim prognosis

Focal injuries

- Extradural haemorrhage (aka epidural hemorrhage)

— Uncommon.

— Lenticular shaped on CT

— Most commonly (80%) due to tearing of middle meningeal artery due to a temporal fracture

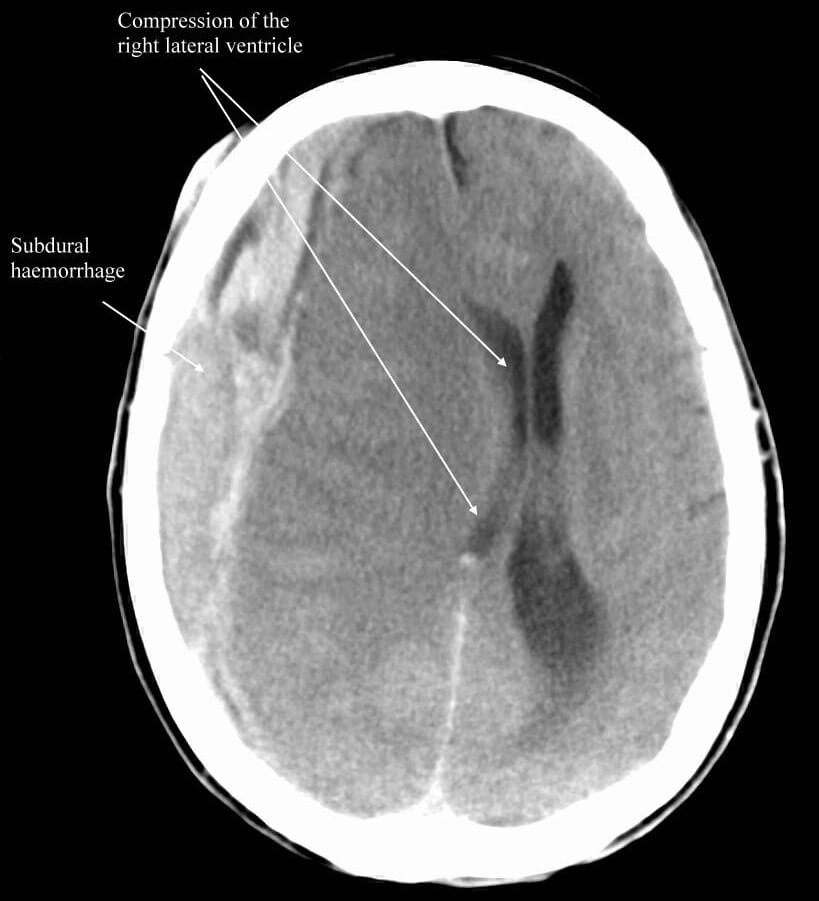

— Classically (i.e. <50%) have lucid period after injury before subsequently deteriorating (aka “talk and die”). - Subdural hemorrhage

— More common — especially in the presence of cerebral atrophy (e.g. elderly and alcoholics)

— Concave shaped on CT

— Due to tearing of veins draining cerebral cortex.

— May present as acute or chronic - Intracerebral hemorrhage

— Ranging from contusions to haematoma.

— Can evolve over time.

— Some advocate observation and / or repeat scanning in 24-48 hours.

All of these lesions may occur in isolation or in combination, and may present with altered mental state for focal neurological deficits. Neurosurgical consultation is required and operative intervention may be necessary. Intracranial lesions are more likely in the presence of skull fractures.

Examples of CT Head findings:

References

- Fildes J, et al. Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual (8th edition), American College of Surgeons 2008.

- Fine Tuning the Injuried Brain. LITFL

- Legome E, Shockley LW. Trauma: A Comprehensive Emergency Medicine Approach, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Marx JA, Hockberger R, Walls RM. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (7th edition), Mosby 2009. [mdconsult.com]

- Resus.ME — Burr holes by emergency physicians.

- Stiell IG, Clement CM, Rowe BH, Schull MJ, Brison R, Cass D, Eisenhauer MA, McKnight RD, Bandiera G, Holroyd B, Lee JS, Dreyer J, Worthington JR, Reardon M, Greenberg G, Lesiuk H, MacPhail I, Wells GA. Comparison of the Canadian CT Head Rule and the New Orleans Criteria in patients with minor head injury. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28;294(12):1511-8. PubMed PMID: 16189364. [Fulltext]

- Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974 Jul 13;2(7872):81-4. PubMed PMID: 4136544.

CLINICAL CASES

Trauma Tribulation