Vincent Cope

Sir Vincent Zachary Cope (1881-1974) was an English surgeon and medical historian

Working mainly at St Mary’s Hospital and the Bolingbroke Hospital in London, Cope brought clinical rigour to bedside diagnosis, culminating in Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen (1921), which ran to 14 editions and became a standard worldwide. The book outlined clinical examination and diagnostic signs Cope believed had ‘never previously been recorded or to which insufficient attention is usually paid’ including the localising diagnostic value of phrenic shoulder pain, the area of hyperaesthesia caused by a distended inflamed appendix, the pathognomonic axillary area of liver resonance in cases of perforated ulcer and the Cope psoas test and Cope obturator test for appendicitis.

Cope’s surgical outlook was shaped by war and public service. During the First World War he served with the Royal Army Medical Corps, including three years in Mesopotamia, where managing dysentery and its complications led to his first monograph on the surgical aspects of dysentery and liver abscess. In the Second World War he was a senior figure in the Emergency Medical Service and, afterwards, chaired Ministry of Health committees on hospital facilities, medical staffing and the training of auxiliaries.

Cope developed a substantial second career in medical history. A long-serving member and honorary librarian of the Royal Society of Medicine, he wrote on the evolution of abdominal surgery and the acute abdomen, and institutional histories and biographies of figures such as William Cheselden, Florence Nightingale, and Sir John Tomes. Across both surgery and history, his legacy lies in his clinical ethos: to “be a physician first, then a surgeon,” to trust hand, ear and eye, and to teach through memorable concepts.

Biographical Timeline

- Born on February 14, 1881 in Hull, Yorkshire, youngest of ten children to Thomas John Cope, Methodist minister, and Celia Anne Crowle.

- 1899 – Head boy at Westminster City School; awarded the school gold medal

- 1900 – Wins entrance scholarship to St Mary’s Hospital Medical School.

- 1905 – Qualifies MB BS (Hons) with distinction in surgery and forensic medicine; appointed house physician to Dr David Lees, whose work on abdominal inflammations shapes Cope’s lifelong interest in the acute abdomen.

- 1907 – MD, University of London.

- 1909 – MS London and FRCS; rises through junior surgical posts at St Mary’s.

- 1911 – Elected assistant surgeon (later surgeon) to St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington. Cope spent virtually his entire consultant career as a general surgeon at St Mary’s Hospital, London, where his name lives on in the Zachary Cope ward.

- 1912 – Joins the staff of the Bolingbroke Hospital, London.

- 1914 – Enlists in the Royal Army Medical Corps; serves at the 3rd London General Hospital.

- 1916–1919 – Posted to Mesopotamia (Baghdad and region); mentioned in despatches. Wartime experience with dysentery leads to his first book, Surgical Aspects of Dysentery

- 1922 – First edition of Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen; text will reach 14 editions over the next 50 years.

- 1939–1945 – Second World War: serves as sector officer in the Emergency Medical Service; later edits two clinical volumes of the Official History of the War of 1939–45 (Medicine and Pathology 1952; Surgery 1953).

- 1947 – Publishes The Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen in Rhyme under the pseudonym “Zeta”.

- 1949–1952 – Chairs Ministry of Health committees on hospital facilities, medical manpower and training of auxiliaries; edits their influential reports.

- 1951 – Honorary Fellow and honorary librarian of the Royal Society of Medicine.

- 1953 – Knighted (Knight Bachelor) for his work on the official medical history of the Second World War.

- 1955 – Succeeds Lord Haden-Guest as chairman, National Medical Manpower Committee.

- 1961 – Elected Honorary Fellow of the Faculty of the History of Medicine and Pharmacology, Society of Apothecaries

- 1972 – Revises the 14th edition of Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen at age 90.

- Died on December 28, 1974 Oxford, England, aged 93

Medical Eponyms

Cope obturator test (1919)

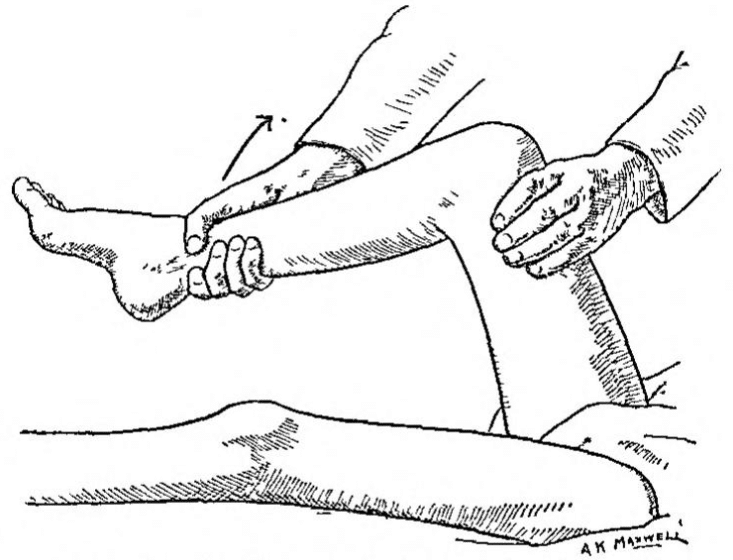

The examiner stands to the right of the patient with the right thigh slightly flexed. The limb is then fully rotated at the hip, first internally and then externally. [aka thigh-rotation test; obturator test]

The right thigh is slightly flexed (so as to relax the psoas muscle) by the surgeon, who stands on the right of the patient: the limb is then fully rotated at the hip, first internally and then externally, so as to put the obturator internus through a full range of movement. The sign is positive if the patient complains of hypogastric pain when the limb is moved in this manner

Cope 1919

May be positive with conditions causing irritation to the obturator internus muscle e.g. inflammatory fluid in the pelvis, abscess, or perforated appendix. An inflamed appendix located in the pelvic brim may cause a positive test when apposed against the obturator internus muscle. Cope obturator sign sensitivity (8%); specificity (94%) in diagnosing acute appendicitis. [Berry]

Since the fascia covering the obturator internus is fairly dense, the test is not positive unless the inflammation is considerable; and, with a positive result, one always expects the appendix to be adherent to, or even an abscess to be contiguous to, the fascia. I have found this sign of assistance not only in cases of appendicitis, but also in other pelvic conditions such as rupture ectopic gestation, and I have no doubt that it will often prove of value in doubtful cases

Cope 1919

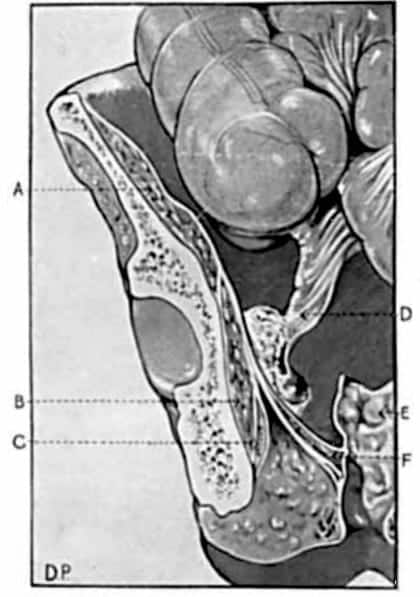

Figure 42: Relationship of pelvic appendix to the obturator internus muscle. An appendicular abscess seen in contact with the fascia over the obturator internus. Cope 1919

Cope psoas test (1921)

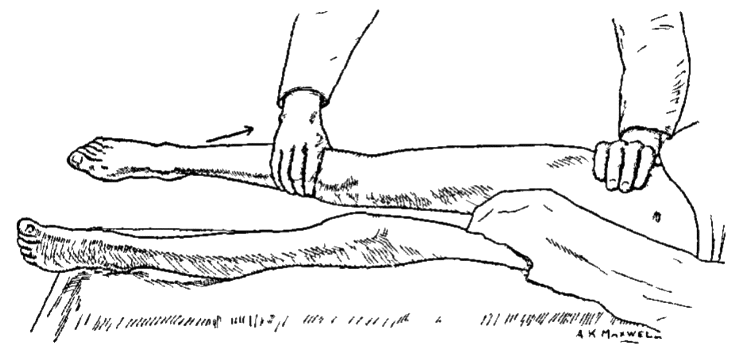

The patient is lying in the lateral decubitus position opposite the side where the pain is located. Extension of the thigh causes pain. [aka Ilio-psoas rigidity; psoas extension test; Obraztsova sign]

It is well known that if there be an inflamed focus in relation to the psoas muscle the corresponding thigh is often flexed by the patient to relieve the pain. A lesser degree of such contraction (and irritation) can be determined often by making the patient lie on the opposite side and extending the thigh on the affected side to the full extent. Pain will be caused by the maneuver if the psoas is rigid from either reflex or direct irritation (Fig 6.). The value of the test is diminished if the abdominal wall be rigid. The psoas-test is not so easily elicited when the inflammation becomes subacute.

Cope 1921

May be positive in retrocecal appendicitis as well as primary/secondary psoas abscess. In appendicitis, the inflamed retrocecal appendix lying against the psoas muscle. In severe cases, the inflammation may cause a fixed flexion deformity of the right hip. Cope psoas test sensitivity (13-42%); specificity (79-97%); a positive likelihood ratio of 2.0 for detecting appendicitis. [Izbicki, Berry]

Cope’s sign (1970)

So-called Cope sign, more accurately the cardio-biliary reflex, refers to reflex sinus bradycardia or atrioventricular (AV) block triggered by acute gallbladder disease, most often calculous or acalculous cholecystitis, and mimicking primary cardiac pathology typically with normal troponin and structurally normal echocardiography

Clinically, patients may present with epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, sometimes central chest pain, accompanied by marked bradycardia or heart block. ECG changes may imitate acute coronary syndrome or primary conduction disease, creating obvious potential for misdiagnosis and unnecessary cardiology work-up, especially when troponin and echocardiography are normal.

1970 – Sir Zachary Cope published a personal case report, “A sign in gall-bladder disease,” describing the early phase of his own acute cholecystitis. He noted sudden severe epigastric pain with loss of appetite, and on self-examination a rounded, tense, non-tender swelling in the gall-bladder area “about the size of a small golf-ball”. The pain and swelling then subsided, only for classic right hypochondrium pain and tenderness to develop several hours later. At operation the gallbladder was acutely inflamed and partly necrotic. He concluded that early acute cholecystitis may present with epigastric pain and a distended but non-tender gallbladder that decomposes before typical RUQ signs appear. Bradycardia was not part of his description.

1971 – O’Reilly & Krauthamer publish “Cope’s sign’ and reflex bradycardia in two patients with cholecystitis”. They summarise Cope’s account as gallbladder disease presenting with heavy epigastric or central chest pain and a palpable gallbladder, initially thought to represent coronary ischaemia.

They then describe “two similar cases that were brought to our attention because of their simulation of a cardiac condition,” and describe two men with chest pain, diaphoresis and marked sinus bradycardia, later found to have acute cholecystitis; the bradycardia responded to atropine and cholecystectomy.

In context, “Cope’s sign” in their title appears to refer to Cope’s clinical picture of gallbladder disease mimicking a cardiac event, with reflex bradycardia as an associated feature in their two cases. They never state explicitly that Cope’s sign is bradycardia.

Subsequent authors, reading only the title and the bradycardic cases, have progressively interpreted Cope’s sign as “reflex bradycardia in cholecystitis”, effectively equating the eponym with the cardio-biliary reflex rather than with Cope’s original description of cholecystitis evolution.

1970s–2010s – Consolidation as cardio-biliary reflex

Subsequent reports broadened the spectrum from simple sinus bradycardia to high-grade AV block and even asystole during biliary colic or acute cholecystitis, typically resolving after cholecystectomy or atropine. These papers increasingly used “Cope’s sign” interchangeably with cardio-biliary reflex, while emphasising that cardiac enzymes remain normal and that the ECG changes are extracardiac in origin.

Current usage

Contemporary literature is mixed: some authors still describe bradycardia or AV block from gallbladder disease as Cope’s sign or “Cope’s cardio-biliary reflex”, while others, especially in historical and educational contexts, prefer to avoid the eponym for gallbladder disease and restrict Cope’s sign to Cope’s original psoas test in appendicitis, using cardio-biliary reflex for gallbladder-induced bradyarrhythmia.

Major Publications

Medical texts

- Cope VZ. The thigh-rotation or obturator test: A new sign in some inflammatory conditions. Br J Surg. 1919; 7: 537. [Cope obturator test]

- Cope VZ. Surgical aspects of dysentery including liver abscess. 1921

- Cope VZ. The early diagnosis of the acute abdomen, 1921. [1926, 1928, 1963, 1972]

- Cope VZ. The Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen. 1921 [Cope Psoas sign]

- Cope VZ. The diagnosis of the acute abdomen in rhyme [Pseudonym ‘Zeta’]. 1947

- Cope VZ. Medicine and pathology. 1952

- Cope Z. A sign of gall-bladder disease. Br Med J. 1970 Jul 18;3(5715):147-8. [Cope sign]

Medical History

- Cope VZ. A History of the acute abdomen. Oxford Univ. Press, 1965

- Cope VZ. Pioneers in acute abdominal surgery. Oxford, 1939

- Cope VZ. The versatile Victorian: being the life of Sir Henry Thompson, Bt. 1820-1904. 1951

- Cope VZ. William Cheselden 1688-1752. 1953

- Cope VZ. Surgery: History of the Second World War. 1953

- Cope VZ. The History of St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School. 1954

- Cope VZ. A Hundred Years of Nursing at St Mary’s Hospital. 1955

- Cope VZ. Florence Nightingale and the doctors. Museum Press, 1958.

- Cope VZ. The Royal College of Surgeons of England: A History. 1959

- Cope VZ. Six disciples of Florence Nightingale. Pitman Medical Publishing Co., 1961

- Cope VZ. Some famous general practitioners and other medical historical essays. 1961

- Cope VZ. Sir John Tomes: A Pioneer of British Dentistry. 1961

- Cope VZ. Contributions to the history of surgery from 1912 to 1962. Proc R Soc Med. 1963;56(Suppl 1):37-9.

- Cope VZ. A history of the acute abdomen. 1965

- Cope VZ. Almroth Wright: founder of modern vaccine-therapy. 1966

- Cope Z. The influence of the free dispensaries upon medical education in Britain. Med Hist. 1969 Jan;13(1):29-36.

Be a physician first, then a surgeon

Advice given to Cope by his mentor Dr David Lees

References

Biography

- Obituary: Sir Vincent Zachary Cope. Br Med J. 1975 Jan 11; 1(5949): 98–99.

- Porritt. Vincent Zachary Cope 1881-1974. Br J Surg. 1975 Aug;62(8):668-9.

- Lefanu W. Vincent Zachary Cope, Kt., M.D., M.S., F.R.C.S. Med Hist. 1975 Jul;19(3):307-8.

- Vincent Zachary Cope. Lancet. The Lancet, 1975; 305(7898): 115-117

- Eastcott HH. Sir Zachary Cope. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1975 May;56(5):276-7.

- Burke PF. The dexterous hand; Zachary Cope, surgeon and author 1881-1974. Surgical News. The Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. 2016;17(1):40-42

- Biography: Sir Vincent Zachary Cope. Plarr’s Lives of the Fellows Online. Royal College of Surgeons of England

- Bibliography. Cope, Zachary 1881-1974. WorldCat Identities

Eponymous terms

- Carling ER. British Surgical Practice: Abdominal Emergencies to Autonomic Nervous System. 1947; I: 293-319

- Berry J, Malt RA. Appendicitis near its centenary. Ann Surg. 1984; 200(5): 567-575.

- Izbicki JR et al. Accurate diagnosis of acute appendicitis: A retrospective and prospective analysis of 686 patients. Eur J Surg. 1992; 158(4): 227-231

- Schwaitzberg S. Celebrating 100 years of Cope’s Early Diagnosis of the AcuteAbdomen. Surgery. 2023 Oct;174(4):874-879.

- Zachary Cope ward. St Mary’s Hospital

- Cadogan M. Cope Psoas test. Eponym A Day. Instagram

- Cadogan M.Appendicitis eponymous signs. Eponymythology

Cope’s sign

- Kaufman JM, Lubera R. Preoperative use of atropine and electrocardiographic changes. Differentiation of ischemic from biliary-induced abnormalities. JAMA. 1967 Apr 17;200(3):197-200

- O’Reilly MV, Krauthamer MJ. “Cope’s sign” and reflex bradycardia in two patients with cholecystitis. Br Med J. 1971 Apr 17;2(5754):146.

- Lau YM, Hui WM, Lau CP. Asystole complicating acalculous cholecystitis, the “Cope’s sign” revisited. Int J Cardiol. 2015 Mar 1;182:447-8.

- Ola RK, Sahu I, Ruhela M, Bhargava S. Cope’s sign: A lesson for novice physicians. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020 Oct 30;9(10):5375-5377.

- Mainali A, Adhikari S, Chowdhury T, Shankar M, Gousy N, Dufresne A. Symptomatic Sinus Bradycardia in a Patient With Acute Calculous Cholecystitis Due to the Cardio-Biliary Reflex (Cope’s Sign): A Case Report. Cureus. 2022 Jun 1;14(6):e25585.

- Yale SH, Tekiner H. Clarifying misconceptions about Cope’s sign. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022 Jun;11(6):3378-3379.

- Shehata R, Anos A, Mohammed MFK, Hekal M, Elatiky M. The Cardio-Biliary Reflex in Gallbladder Disease: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. 2025 Oct 10;17(10):e94272.

Eponym

the person behind the name

MBBS (Hons) FCEM. Clinical Lead Emergency Medicine | St Mary's Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |