Warfarin toxicity

Over anticoagulation is a common problem with warfarin and acute intoxication maybe in those with or without an anticoagulation requirement. This can make the approach to treatment difficult when considering the need for therapeutic anticoagulation and expert advice maybe required.

On a trivia note warfarin was invented with the help of the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) and hence the origin of the name (-arin indicating the link with coumarin). In 1933 a farmer from Deer Park showed up unannounced at the School of Agriculture and walked into a professor’s laboratory with a milk can full of blood which would not coagulate. In his truck, he had also brought a dead heifer and some spoiled clover hay. He wanted to know what had killed his cow. In 1941 Karl Paul Link gave him his answer and the rodent killer was born.

Toxic Mechanism:

Vitamin K which is a cofactor for the synthesis of clotting factors II, VII, IX and X (plus protein C and S), warfarin inhibits Vitamin K. The half life of the coagulation factors are 6, 24, 40 and 60 hours (VII, IX, X and II, respectively) and hence it takes 12 hours for any effect of warfarin to become recordable. Peak effects are observed by 72 hours.

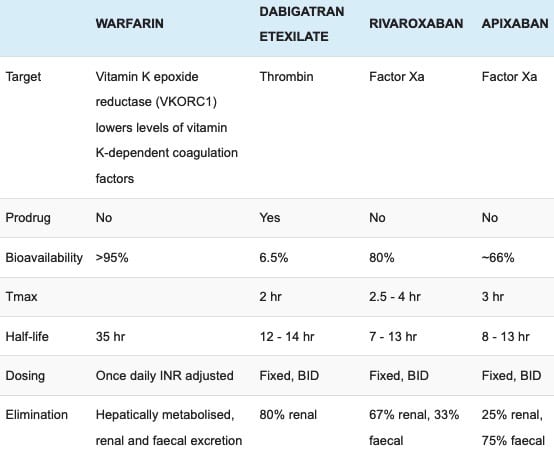

Toxicokinetics:

- Completely absorbed following oral administration

- Small volume of distribution 0.2 L/kg

- 99% protein bound

- Hepatic metabolism and enterohepatic recirculation.

- Warfarin and its metabolites are excreted in urine and faeces with an elimination half life of 35 hours.

Resuscitation:

- Rarely required

- Uncontrolled or life threatening haemorrhage:

- Fresh frozen plasma (10 – 15 ml/kg) if prothrombin concentrate complex is not available

- Prothrombin concentrate complex (25 – 50 IU/kg)

- Vitamin K 5 – 10 mg intravenous

Risk Assessment

- Patient on therapeutic warfarin have significant risk of haemorrhage, for each unit rise in INR there is a 3.5x fold risk of bleeding.

- Patients not on warfarin who have an acute ingestion:

- <0.5 mg/kg are unlikely to increase their INR significantly.

- >2 mg/kg can produce a significant increase in INR within 72 hours.

- Active bleeding requires emergent treatment.

- Clinical features:

- Usually asymptomatic

- Severe coagulopathy may present as bruising, petechial or puerperal rashes, gingival bleeding, epistaxis, gastrointestinal bleeding or haematuria.

- Children: A single ingestion of <0.5 mg/kg does not present a risk of significant anticoagulation and does not require investigation or treatment.

Risk stratification for high risk of bleeding

- Recent major bleed (within 4 weeks)

- Major surgery within the past 2 weeks

- Thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 50 x 10,000000000/L)

- Known liver disease

- Concurrent anti platelet therapy

Risk stratification if anticoagulation is reversed

- High Risk:

- mechanical mitral valve

- mechanical aortic valve with arrhythmia or PH thromboembolism

- Moderate Risk:

- AF with valvular heart disease, previous stroke or embolism

- Cardiomyopathy with heart failure, previous stroke or embolism

- Biological heart valves (1st 3 months)

- Past history of multiple PE/DVT

- Uncomplicated DVT (<2 months)

- DVT/PE with lab-confirmed hyper coagulable blood

- Past history of systemic arterial emboli

- Mechanical aortic valve without either arrhythmia or past history of thromboembolism

- Low risk:

- AF without either valvular heart disease, previous stroke or embolism

- Cardiomyopathy without either heart failure, previous stroke or embolism

- Biological heart valves (except 1st 3 months)

- Uncomplicated DVT (>2 months)

- Cerebrovascular disease

- Post AMI (mural thrombus prophylaxis)

- Vascular surgical prosthetic grafts

- Post vascular-stent insertion.

Supportive Care

- General supportive measures

Investigations

- Screening: 12 lead ECG, BSL, Paracetamol level

- Specific:

- INR: If not previously on warfarin the INR will not change in the first 12 – 24 hours. A normal INR at 48 hours excludes warfarin toxicity

- In patients with a therapeutic requirement an INR should be measured on presentation and every 6 hours.

Decontamination:

- Activated charcoal is not indicated following ingestion unless the patient has a therapeutic requirement and has taken an overdose within the past 1 hour.

Enhanced Elimination

- Not clinically useful.

Antidote (and treatment variations)

- Vitamin K is administered prophylactically to those without the therapeutic requirement who have taken an acute ingestion that will result in anticoagulation as per the risk assessment.

- Those who have a therapeutic requirement must have their vitamin K administration titrated to keep the INR within range.

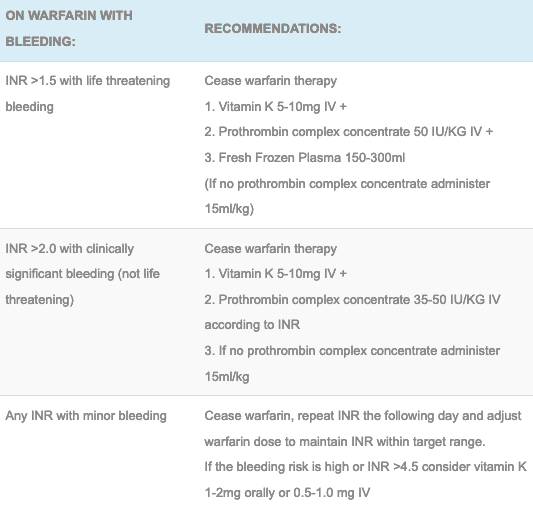

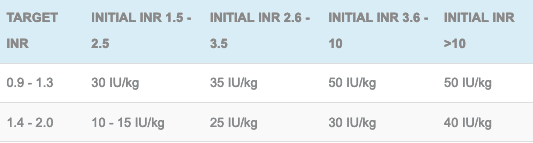

- Below is a number of tables with recommended treatments for a raised INR with and without bleeding and also a proposed regimen for titrating prothrombin complex concentrate. Be aware local protocols maybe different and that close follow up of the INR should always be performed.

Treatment for a raised INR with bleeding:

Treatment for a raised INR without bleeding:

Dosing of prothrombin complex concentrate to a targeted INR (patients will still need a dose of vitamin K to prevent rebound elevation of the INR and a check INR 30 minutes post PCC):

Disposition

- A child who ingests <0.5 mg/kg does not require assessment or observation.

- A child who ingests >0.5 mg/kg can be given 10 mg of vitamin K PO and discharged. They do not require INRs or follow up.

- Patients who have no therapeutic requirement for anticoagulation are given 5mg of vitamin K BD for 2 days and medically cleared. A follow up INR is required at 48 hours. Where this management takes place will need liaison with mental health.

- Patients with a therapeutic requirement for anticoagulation are admitted to receive titrated doses of vitamin K.

- Over-anticoagulation is managed as per the table in antidote section.

References and Additional Resources:

Additional Resources:

- CCC – Warfarin

- Toxicology Conundrum 015 — Little Johnny and Grandad’s warfarin

- Toxicology Conundrum 016 — Warfarin deliberate self poisoning

- Toxicology Conundrum 021 — Supratherapeutic INR

References:

- Baker RI, Coughlin PB, Gallus AS et al. The Warfarin Reversal Consensus Group Warfarin reversal: consensus guidelines, on behalf of the Australasian Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Medical Journal of Australia 2004: 181(9):494-497.

- Isbister GK, Hackett LP, Whyte IM. Intentional warfarin overdose. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 2003; 25(6):715-722

- Levine M, Pizon AE, Padilla-Jones A, Ruha A-M. Warfarin overdose: a 25-year experience. Journal of Medical Toxicology 2014: dos 10.1007

- Tran HA, Chanilal SD, Harper PL et al. An update of consensus guidelines for warfarin reversal. Medical Journal of Australia 2013: 198(4):1-7

Toxicology Library

DRUGS and TOXICANTS

Dr Neil Long BMBS FACEM FRCEM FRCPC. Emergency Physician at Kelowna hospital, British Columbia. Loves the misery of alpine climbing and working in austere environments (namely tertiary trauma centres). Supporter of FOAMed, lifelong education and trying to find that elusive peak performance.