A Case of Epistaxis

Case Study

A 34 female presents to ED at 2am, post waking up with blood all over her pillow, and a continuous ooze of blood from her right nostril.

On examination the patient is alert and oriented, BP 110/60, pulse 95, respiratory rate 22, Sp02 98% room air, and has no past medical history. The patient reports having a sinus infection of late which she’s has been using an antihistamine nasal spray to treat.

Epistaxis:

- Epistaxis is a frequent complaint

- 60% of the population will with suffer from a nose bleed during their lifetime, and 6% will require medical attention.

- Majority of epistaxis occurs between the ages of 2-10 and 50-80 years old.

- Epistaxis results from an interaction of factors that damage the nasal mucosal lining, affect the vessel walls, or alter the coagulability of the blood.

- Emergency physicians have a 90% success rate at treating epistaxis in emergency department, and only have to refer 10% to ENT for further assessment and management

Causes of Epistaxis:

Local trauma:

- Nose picking

- Facial trauma

- Foreign bodies

- Nasal or sinus infections

- Nasal septum deviation

Environmental:

- Dry cold conditions (presentations increase during winter)

- Prolonged inhalation of dry air (Oxygen)

Iatrogenic:

- Nasogastric tube insertion

- Nasotracheal intubation

Medicinal:

- Topical corticosteroids and antihistamines

- Solvent inhalation (huffing)

- Snorting cocaine

- Anticoagulants: Aspirin, warfarin, platelet inhibitors

Coagulopathies:

- Inherited coagulopathies: von Willebrand disease, haemophilia A & B

- Splenomegaly

- Thrombocytopenia

- Platelet disorders

- Liver disease

- Renal failure

- Chronic alcohol abuse

- AIDS

Vascular Abnormalities:

- Sclerotic vessels

- Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Neoplasm

- Aneurysms

- Septal perforation/deviation

- Endometriosis

Hypertension:

- Controversial topic and is often misunderstood in epistaxis – see Hypertension and Epistaxis.

- Hypertension is rarely a direct cause of epistaxis

- Epistaxis is however more common in hypertensive patients this is postulated to be caused from long standing hypertension causing vascular fragility of the blood vessels.

- Epistaxis in patients presenting to ED, will generally have an associated anxiety that will increase blood pressure.

Despite multiple causes for epistaxis, literature shows that in 85% of cases no causes in found.

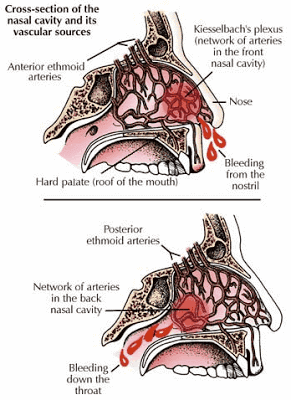

Anatomy and Physiology of Epistaxis:

- The nose is supplied with an extensive vasculature with multiple anastomosis.

- 90% of epistaxis occurs in the anterior nasal septum, from Littles area which contains the Kiesselbach plexus of vessels.

- The other 10% occur posteriorly, along the nasal septum or lateral nasal wall.

- The blood supply of the nasal septum is from the internal carotid through the anterior and ethmoidal arteries, and from external carotid through the greater palatine, spenopalatine and superior labial arteries.

Assessment of the patient presenting with Epistaxis:

History:

Obtain the following:

- Laterality, duration, frequency

- Severity, estimated blood loss

- Any contributing or inciting factors

- Family history or bleeding disorder

- Past medical history

- Current medications

Physical Examination:

- Focus on trying to identify if the bleed is coming anteriorly or posteriorly.

- Suctioning or blowing of the nose to clear away clots, and application of topical vasoconstrictors or anaesthetics will help with visualisation

- Gently insert nasal speculum and spread naris vertically, a good light source will be also required to assist visualisation of bleeding area.

- A posterior source of bleeding is suggested by failure to visualise an anterior source, bleeding from both nares, and the visualisation of blood in the posterior pharynx.

Investigations:

- Patients will large amounts of bleeding should have a full blood count to check haemoglobin level, and a group and hold in case transfusion is required.

- Patients taking warfarin should have an INR checked.

- Coagulation studies are only of benefit in patients with a known coagulopathy or chronic liver disease, and should not be routine in patients presenting with epistaxis.

- Other bloods test should only be ordered if past medical history warrants further investigation (renal failure = U&E, chronic alcohol abuse = LFTs), and literature has shown they rarely change your management and add considerably to the cost of treating these patients.

- Radiological investigations have little role in the management of epistaxis, CT scan is indicated if neoplasm suspected, and would generally be arranged post consultation with your ENT specialist.

Emergency Department Management:

Prehospital Care:

- Good effective first aid should stop 90-95% of nose bleeds.

- Provide a calm and quite area for the patient to decrease anxiety

- The patient should position them self either forward or backward, which ever provides the most comfort and prevents the patient from swallowing or aspirating any blood draining into the pharynx. Tip: Fresh blood is irritating to the stomach and will cause nausea and vomiting.

- Pressure should then be applied by pinching the anterior aspect of the nose for 15-20mins, which provides tamponade to the anterior septal vessels. Patients should be shown the correct was to apply pressure by avoiding the nasal bones, by pressing more distally the nasal ala against the septum.

- Some authors advocate placing ice pack to the nape of the neck with belief it produces a reflex vasoconstriction in the nasal mucosa, however there is little research or evidence to support this.

Initial Management and Resuscitation:

In extreme cases patients can present with uncontrolled haemorrhage, standard resuscitation principles should be applied.

Airway:

- Risk of airway obstruction from blood in the posterior pharynx, or decreased level of consciousness from hypovolaemia.

- Place patient in position to assist in managing the blood loss, may require frequent suctioning.

- Be prepared to secure and place a definitive airway (ETT)

Breathing:

- Assess depth of breathing and respiratory rate,

- Remember a noisy airway is an occluded airway

- Provide high flow oxygen via non re-breather mask

Circulation:

- Assess heart rate, blood pressure and capillary refill

- Patient at risk for severe haemorrhage place x2 large bore IV, check HB, cross match blood, and start fluid resuscitation

Disability:

- Monitor patients level of consciousness this help determine the severity of haemorrhage

Exposure:

- Keep patient warm to prevent coagulopathy

- If epistaxis is caused by major trauma, always examine from for other injuries

Patients can and have died from epistaxis be prepared to resuscitate!!!

Vasoconstriction:

- Vasoconstriction can be achieved by the application of agents topically or soaked cotton pledgets inserted into the nasal cavity.

- Local anaesthesia (Lignocaine) should be used were possible to provide analgesia.

- Agents available include 1:1000 Adrenaline, Co-Phenylcaine, and Oxymetazoline, and are used for their vasoconstriction properties.

- Pledget inhalation is a risk especially in patients with decreased level of consciousness and children.

- Vasoconstrictors have been shown to be extremely effective in anterior epistaxis, aid in the visualisation of the bleeding site, and assist if packing is required.

- Following successful application of topical vasoconstriction, patients should be encouraged to apply topical steroid creams, and petroleum jelly to the nasal cavity weekly for six weeks, this has been shown to have a 94% success rate of resolution of symptoms.

Suction:

- Suction should be available and easy accessible to help remove clots.

- Getting the patient to blow their nose can also be an effective form of suction

- An angled Fraser sucker, 10-12 French gauge, is preferred to allow evacuation of the anterior and middle nasal cavity

Cautery:

Chemical:

- Chemical cautery involves the application of silver nitrate sticks, by wiping the tip of the silver nitrate stick over Little’s area until it becomes discoloured and grey.

- The area should be suctions and as dry as possible to maximise the effectiveness of silver nitrate sticks, localised pain can occur on application.

- The sticks should be applied for 4-5secs until a grey residue or eschar develops.

- Only one septum should be cauterised using silver nitrate, as bilateral can cause sepal perforation

- Generally effective in anterior bleeds, however there is a risk of rebleeding.

Electrocautery:

- Generally performed by ENT specialist after effective topical anaesthetic needs to be provide first.

- The red-hot electrocautery loop is passed over the mucosal blood vessels effecting cautery.

- Topical antibiotics and/or petroleum jelly can be used post-operatively.

Packing:

- Anterior packing is required when the bleeding fails to stop with vasoconstrictors and cautery.

- Options include traditional nasal packing, a prefabricated nasal sponge, an epistaxis ballon, or absorbable materials.

- Nasal tampons that are moistened, gel-coated, with an inflatable balloon are less painful and show equal effectiveness when compared to dry hydrophilic nasal tampon

Types of packs:

- Traditional Vaseline gauze packing: generally not used these days, as have been supplanted by readily available and more easily placed tampons and balloons.It consist of ribbon gauze soaked in petroleum jelly, and is placed in the back of the nasal cavity as far back as possible, and layered into the naris until it is completely packed. Need to allow both ends of the gauze protrude from the nose to allow ease of removal.

- Compressed sponge/tampon: Merocel is a dehydrated polyvinyl polymer sponge, formed into flat tampons of various sizes. These are inserted into the nasal cavity, and then rehydrate by blood or saline, causing then to expand up the three time their original size, filling the nasal cavity and compressing the source of bleeding.The advantage of these of gauze packing is that they are technically easier to insert, however literature shows no difference in patient pain, and ease of removal compared to gauze packing.

- Anterior epistaxis balloons: Rapid Rhino consist of an outer layer of carboxycellulose that promotes platelet aggregation, with an inflatable balloon that compresses the nasal cavity upon inflation tamponading the bleeding site. Rapid Rhino have been shown to be as effective as nasal tampons and allow for superior patient comfort on insertion and removal.

- Absorbable materials: various non-absorbable packing materials are available, including carboxymethycellulose sponges, and calcium alginate dressings and wicks. These dressing can be left in place for between 1-5 days, but remember the longer the packing is left insitu the increase risk of developing toxic-shock syndrome.

Posterior Packing/ Balloon Catheters:

- Posterior nasal bleeds can be difficult to manage related to the relatively inaccessible site of bleeding and generally don’t respond the above standard medical treatment and packing.

- Analgesia will be required for patients with posterior packing and balloon catheters

- Double balloon catheters consist off of a posterior and anterior balloon, are relatively easy to insert, although cost may limit their use. Generally used in difficult posterior epistaxis.

- The catheter is inserted to the back of the nasopharyngeal space, and then inflate the posterior balloon first and bring forward sealing off the post nasopharyngeal space. Then inflate the anterior balloon to apply pressure to the internal cavity of the nose.

- Saline is preferred over air to inflate balloon as air can leak out causing deflation and further rebleeding.

- Avoid over-inflating balloon catheters as will cause increased discomfort, rupture of the balloon, or pressure necrosis of the nasal mucosa.

- A Foley catheter can be used 10-14 French with 30ml balloon as an alternative.

Disposition:

- Arrange admission for patients with posterior packing, requiring oxygen, and patients with difficult to manage bleeds.

- Patient with anterior packing can generally be discharged home, with packing insitu, with follow up arranged in 48-72 in the ENT clinic. Provided antibiotics and oral analgesia.

- Patients with chronic epistaxis should receive medical followup to investigate anaemia from chronic blood loss, and coagulopathies.

- Uncontrolled severe epistaxis can sometimes require endoscopic cautery, embolization or artery ligations, patients at risk should receive early ENT review.

- Consider Tranexamic acid is severe epistaxis as it works as a potent competitive inhibitor of plasminogen activator and thus of the fibrinolytic system, and may therefore prevent clot disintegration and reduce the likelihood of re-bleed.

Medico-legal Pitfalls:

- Nasal packing can lead to serious infection (Toxic shock syndrome), most of literature and ENT specialist recommend prophylactic antibiotics, until evidence supports or refutes this practice its most probably best practice to follow this and treat with broad spectrum antibiotics.

- Posterior nasal packing places the patient at risk of hypoxia and hypoventilation, monitoring for this, and implement treatment promptly should it occur.

- Nasal packing generally slows or causes cessation of haemorrhage, failure to control haemorrhage should prompt urgent ENT review.

- Recurrent unilateral epistaxis should prompt further investigation to rule out neoplasm.

“Nose bleeds occur in those who are beginning to have feeling of lust or who are getting the signs of manliness.

Hippocrates 4th century BC1.

References

- Movin’ Meat Drip, Drip, Drip – more thoughts on epistaxis management

- Awan, M. Iqbal, M. & Imam, S. (2008). Epistaxis: when are coagulation studies justified. Emergency Medicine Journal. 25, 156-157. PMID: 18299365

- Burton, M. & Doree, C. (2009). Interventions for recurrent idiopathic epistaxis (nosebleeds) in children (Review).

- Ghosh, A. & Jackson, R. (2001). Cautery or cream for epistaxis in children. BestBets.org

- Gifford, T. & Orlandi, R. (2008). Epistaxis. Otolaryngol Clinics of North America. 41, 525-536. PMID: 18435996

- Herkner, H. et.al. (2002). Active Epistaxis at ED Presentation is Associated with Arterial Hypertension. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 20, 92-95. PMID: 11880870

- Kucik, C. & Clenney, T. (2005). Management of Epistaxis. American Family Physician. 71(2), 71-78. PMID: 15686301

- Mackaway-Jones, K. & Morton, R. (2001). Little evidence for either packing or cautery in anterior epistaxis. BestBets.org

- McIntosh, L. & Teece, S. (2004). Anterior epistaxis-does cooling decrease bleeding? BestBets.org

- Middleton, P. (2004). Epistaxis. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 16, 428-440. PMID: 15537406

- Pashen, D. & Stevens, M. (2002). Management of epistaxis in general practise. Australian Family Physician. 31(8), 1-5. PMID: 12189661

- Phelps, S. (2005). Inflatable nasal tampons are less painful than dry hydrophilic nasal tampons. BestBets.org

- Schlosser, R. (2009). Epistaxis. The New England Journal of Medicine. 360, 784-789. PMID: 19228621

CLINICAL CASES

ENT equivocation

Emergency nurse with ultra-keen interest in the realms of toxicology, sepsis, eLearning and the management of critical care in the Emergency Department | LinkedIn |