Brown Snake

The Brown snake is the most common culprit for severe envenomations in Australia. It classically causes a Venom-induced consumptive coagulopathy (VICC) or a partial VICC (20% of envenoming). In a few cases Brown snakes are responsible for collapse and in approximately 5% of those envenomed cardiac arrest, the exact mechanism is unknown but probably secondary direct cardiotoxicity. Fortunately the majority of brown snake bites are dry bites.

The Brown snake has a number of names including: Dugite, spotted brown snake, peninsula brown snake, Ingram’s brown snake, Western brown snake, ringed brown snake, tropical brown snake and the eastern brown snake.

Resus

- Potential to be immediately life threatening, the patient should initially be managed in an area capable of resuscitation.

- Early threats to life include hypotension and uncontrolled haemorrhage.

- Cardiac arrest in 5% of those envenomed, undiluted brown snake antivenom should be administered as a rapid IV push and resuscitation continued along standard protocols.

Risk Assessment

Typical symptoms include:

- Clinically a VICC may present with bleeding gums or bleeding around the IV site, rarely this can manifest as an intracerebral haemorrhage or intraabdominal haemorrhage.

- Brown snakes sometimes leave no obvious bite site

- Can cause non-specific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and headaches.

- Brown snakes are responsible for collapse and in approximately 5% of those envenomed cardiac arrest.

- Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) occurs in 10% of envenomations (classic triad of thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia and acute renal failure).

- Myotoxicity does not occur

- Significant neurotoxicity is rare despite a neurotoxin in the venom but mild diplopia and ptosis have been observed.

Supportive Care

1. IV fluids – for myotoxicity and to help prevent complications from myoglobinuria

2. Pressure bandage with Immobilisation (PBI) – Should have been applied pre-hospital, if not apply while awaiting initial investigations.

PBI Video

Investigations

1. Laboratory Tests (At presentation, 1 hour post PBI removal, 6 and 12 hours following the bite): FBC, EUC, CK, INR, APTT, Fibrinogen, D-dimer. Never use point of care testing for D-dimer or INR. If there is no evidence of envenoming at 12 hours after the bite (including 6 hours post PBI removal), the patient is fit for discharge (although not during the night as subtle neurotoxicity maybe missed).

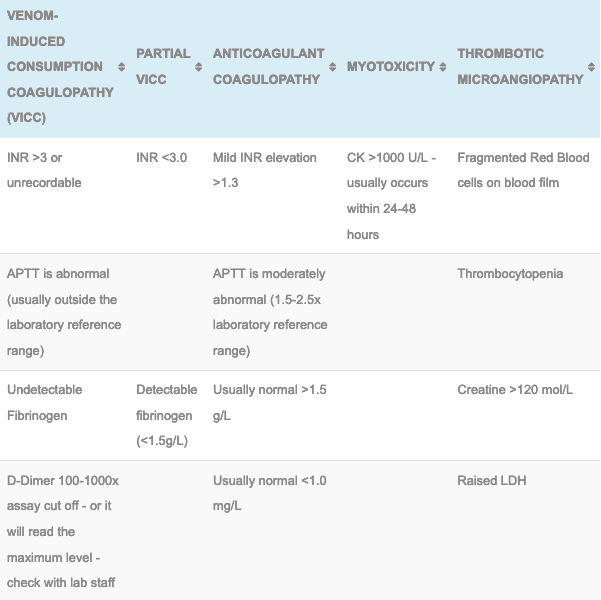

2. Brown snake envenoming is characterised by a VICC or a Partial VICC:

- VICC:

- Elevated INR (>3 or laboratory max or unrecordable)

- Undetectable fibrinogen

- Elevated D-dimer (>100 x normal)

- Partial VICC:

- INR abnormal but <3

- Low but detectable fibrinogen

- Recovery from VICC or partial VICC (INR <2) takes on average 15 hours.

3. Monitor renal function and if VICC has occurred there is a risk of thrombotic microangiopathy indicated by a rise in LDH, deteriorating renal function and platelets with fragmented red blood cells.

4. The Snake Venom Detection Kit (SVDK): This is not used to diagnose envenoming but can be used to determine which monovalent antivenom to use if more than one snake could be responsible for the observed clinical features. This kit does produce false positives and false negatives, caution needs to be used and contacting a clinical toxicologist is highly recommended if your patient is envenomed.

Differential Diagnosis:

- Tiger snake and Brown snake share a similar course early in the presentation. Both can have VICC and can have early collapse. The difference with Tiger envenoming is the development of neurotoxicity and myotoxicity.

- Taipan also develops VICC but is associated with early neurotoxicity and myotoxicity.

Antivenom

- 1 amp CSL monovalent Brown Snake Antivenom: Used in the treatment of envenomation (systemic symptoms, collapse, cardiac arrest or laboratory evidence of VICC or partial VICC) by the brown snake within 12 hours of the bite.

- See Brown Snake Antivenom for dosing, administration and complication details

Disposition

- All patients must be observed in a hospital capable of managing a potential snake bite envenomation, this involves adequate laboratory cover and the ability to administer antivenom and manage potential anaphylaxis.

- Patient with no clinical evidence or laboratory evidence of a VICC or partial VICC at 12 hours post bite are not envenomed and maybe discharged in daylight hours.

- Envenomed patients can be discharged following antivenom and a further 24 hours of observation. They need to have resolving coagulation (INR <2) with no evidence of thrombotic microangopathy and a normal renal function.

Controversies

- Administration of antivenom does not appear to hasten the recovery from VICC, but it may reverse or prevent other manifestations of envenoming.

- Plasmapheresis has been used to treat thrombotic microangiopathy but its utility is still undefined.

- Administration of Fresh Frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate after antivenom administration is associated with earlier recovery from VICC but it does not effect time to discharge and the exact utility to this approach has not be well defined in clinical practise.

References and Additional Resources:

Additional Resources:

- Brown Snake Antivenom

- Approach to the Snakebite Patient

- Tox Conundrum 005 – Snakebite vs Stickbite

- Tox Conundrum 026 – Snakebite Envenoming Challenge

Zeff – James Hayes Fellowship teaching Snakebite

References:

- Allen GE, Brown SCA, Buckley NA et al. Clinical effects and antivenom dosing in brown snake (Pseudonaja app.) envenoming – Australian Snakebite project (ASP-14). PLoS ONE 2012; 7(12):e53188.

- Brown SG, Caruso N, Borland M et al. Clotting factor replacement and recovery from snake venom-induced consumptive coagulopathy. Intensive Care Medicine 2009; 35(9): 1532-538

- Isbister GK, Buckley NA, Page CB et al. A randomised controlled trial of fresh frozen plasma for treating venom-induced consumption coagulopathy in cases of Australian snakebite (ASP-18). Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostats 2013; 11:1310-1318

- Isbister GK, Duffel SB, Brown SGA. Failure of antivenom to improve recovery in Australian snakebite coagulopathy. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 2009; 102(8):563-568

- Isbister GK, Little M, Cull G et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy from Australian brown snake (Pseudonaja) envenoming. Internal Medicine Journal 2007; 37(8):523-528.

- White J. A clinician’s guide to Australian venomous bites and stings: Incorporating the updated CSL antivenom handbook. Melbourne: CSL Ltd, 2012

Toxicology Library

TOXINS

Dr Neil Long BMBS FACEM FRCEM FRCPC. Emergency Physician at Kelowna hospital, British Columbia. Loves the misery of alpine climbing and working in austere environments (namely tertiary trauma centres). Supporter of FOAMed, lifelong education and trying to find that elusive peak performance.