Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis

Cavernous sinus thrombosis in the antibiotic era remains a vital diagnosis to make, as mortality and morbidity remain extremely high if missed.

Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis is a devastating condition, with mortality rates of up to 30% even with treatment. Of survivors, the majority will have permanent sequelae.

In the pre-antibiotic era, mortality was virtually 100%.

When it occurs, it is most commonly the result of infection of:

- The central third of the face.

- The paranasal sinuses.

Rarely, cavernous sinus thrombosis may result from non-infective causes.

The best imaging modality is MRI. If MRI is unavailable in an urgent timeframe, CT venography may be used.

Treatment consists primarily of early and aggressive antibiotics. The role of anticoagulation remains controversial.

History

Cavernous sinus thrombosis was first described pathologically by Scottish physician Andrew Duncan Jnr (1773–1832) in 1821. It was described clinically by English physician Richard Bright (1789–1858) in 1831.

Anatomy

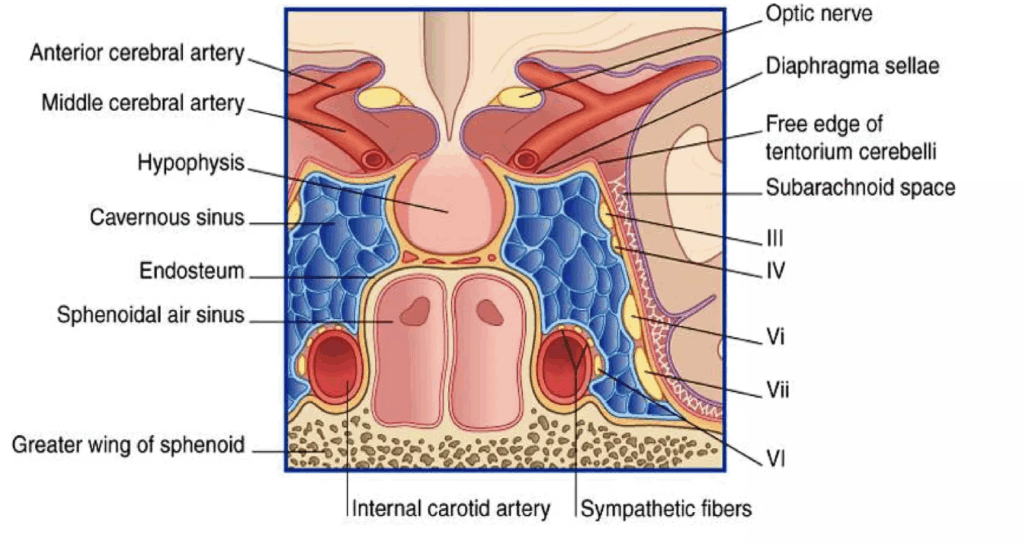

The cavernous sinus is a centrally located dural sinus structure of the middle cranial fossa:

- Surrounds the sella turcica (above) and the sphenoid sinuses (below).

- Sits above the greater wings of the sphenoid bones.

- Lateral: temporal lobes of the brain.

- Anterior: optic chiasm.

Venous Communications

Facial veins have no valves and communicate with the cavernous sinus via:

- Ophthalmic vein → cavernous sinus.

- Facial vein → deep facial vein → pterygoid venous plexus → cavernous sinus.

This allows infective thrombosis of the facial or ophthalmic veins to extend internally.

Structures within the Cavernous Sinus

- Internal carotid artery.

- Third cranial nerve (oculomotor).

- Fourth cranial nerve (trochlear).

- Sixth cranial nerve (abducent).

- Ophthalmic nerve.

- Maxillary nerve.

Pathology

Causes

Infective Causes

- Late complication of infection in:

- Middle third of the face.

- Paranasal sinuses.

- Septic complications of middle third facial fractures.

- Dental infections (maxillary teeth).

- Middle ear infection / mastoiditis.

- Orbital cellulitis.

- Haematogenous spread from remote sites (rare).

Non-infective Causes

- Thrombophilic genetic disorders:

- Factor V Leiden mutation.

- Prothrombin G20210A mutation.

- Antithrombin III, protein C, or protein S deficiency.

- Severe dehydration.

- Trauma.

Organisms

Bacterial

- Staphylococcus aureus (most common).

- Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- Pneumococcus.

- Gram-negative bacilli.

- Anaerobes.

Fungal (in immunocompromised patients)

- Aspergillus (most common).

- Mucormycosis.

- Coccidioidomycosis.

Complications

- Septicaemia and death.

- Stroke:

- Internal carotid artery compression/thrombosis.

- Intracranial septic extension:

- Meningitis.

- Cerebral abscess.

- Subdural empyema.

- Orbital extension:

- Destruction of optic nerve or globe.

- Cranial nerve lesions:

- III, IV, VI, ophthalmic nerve, maxillary nerve.

- Pituitary destruction.

Clinical Features

Cavernous sinus thrombosis is typically rapidly fulminant.

Typical Features

- Facial pain / headache:

- Most common early feature.

- Can precede fever, visual disturbance, or cranial nerve signs.

- Fever.

- Visual disturbances.

- Cranial nerve lesions:

- III (oculomotor).

- IV (trochlear).

- VI (abducent — most commonly involved).

- Ophthalmic nerve.

- Maxillary nerve.

- Evidence of primary infection:

- Sinusitis.

- Mid-face infection.

- Middle ear infection.

- Ophthalmic vein congestion:

- Chemosis (conjunctival oedema).

- Exophthalmos.

- Ptosis.

- Pupillary responses:

- Miosis (Horner syndrome) from sympathetic fibre loss.

- Mydriasis from parasympathetic fibre loss (CN III).

- Visual disturbance / loss.

Eye signs may start unilateral but often spread bilaterally within 24–48 hours via sinus interconnections.

- Signs of meningeal irritation:

- Neck stiffness.

- Kernig’s sign.

- Brudzinski’s sign.

- Increased intracranial pressure:

- Drowsiness.

- Confusion.

- Seizure.

- Coma and death.

Investigations

Blood Tests

- FBE.

- CRP.

- U&Es / glucose.

- Blood cultures.

Microbiology

- Microscopy and culture of any purulent discharge.

CT Venogram

- Plain CT may not detect cavernous sinus thrombosis.

- CT venogram increases sensitivity.

- A negative CT venogram does not exclude diagnosis when clinical suspicion is high.

MRI / MRV

- MRI is the imaging modality of choice.

- MRV can also be helpful.

Management

1. Analgesia

- Pain is usually severe; titrated IV opioid will be required.

2. Antibiotics

- Early, aggressive broad-spectrum antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment.

- Example regimen: Tazocin + Metronidazole.

- Duration: typically 3–4 weeks.

- Seek Infectious Diseases input.

3. Anticoagulation

- This remains controversial.

- Potential benefits:

- Halt thrombosis progression.

- Prevent clot propagation.

- Improve antibiotic penetration.

- Potential risks:

- Intracranial bleeding.

- Dissemination of septic emboli.

- Many experts recommend anticoagulation unless there are contraindications (e.g. intracranial haemorrhage).

- Specialist advice is essential.

4. Thrombolytics

- Currently no good evidence supports thrombolysis for cavernous sinus thrombosis.

5. Corticosteroids

- Dexamethasone or hydrocortisone may reduce inflammatory oedema.

- Benefit is uncertain; specialist advice should be sought.

- Essential in cases of pituitary destruction.

6. Surgery

- Surgery on the cavernous sinus is not helpful.

- Drain primary infection source where possible (e.g. sphenoid sinusitis, facial abscess).

Disposition

Consultations to Consider

- Infectious Diseases.

- Ophthalmology.

- Haematology.

- Neurosurgery.

- HDU / ICU as required.

References

Publications

- Duncan Andrew Jnr. Case IV. – Extensive Suppuration of the Cavities of the Petrous Portion of the Temporal Boncy with Chronic Discharge from the Ear In: Contributions to morbid anatomy. The Edinburgh medical and surgical journal 1821; 17: 319-325.

- Bright R. Case LXVI – Inflammation of the Sinuses of the Brain subsequent to a discharge from the Ear, with extensive Disease of the Lungs and Heart In: Reports of medical cases selected with a view of illustrating the symptoms and cure of diseases by a reference to morbid anatomy. 1831; Vol 2: 129-132

- Agayev A, Yilmaz S. Images in clinical medicine. Cavernous sinus thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2008 Nov 20;359(21):2266.

- Plewa MC, Tadi P, Gupta M. Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis. 2023 Jul 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]

FOAMed

- Nickson C. The Red Eye Challenge. LITFL

- Nickson C. Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. CCC

Fellowship Notes

MBBS DDU (Emergency) CCPU. Adult/Paediatric Emergency Medicine Advanced Trainee in Melbourne, Australia. Special interests in diagnostic and procedural ultrasound, medical education, and ECG interpretation. Co-creator of the LITFL ECG Library. Twitter: @rob_buttner

Educator, magister, munus exemplar, dicata in agro subitis medicina et discrimine cura | FFS |