Dominique-Jean Larrey

Dominique-Jean Larrey, Baron de l’Empire (1766-1842) was a French military surgeon

Larrey was Napoleon’s chief surgeon and one of the most influential figures in military medicine. He transformed battlefield medicine by insisting that the wounded be treated immediately and impartially, regardless of rank or nationality. His innovations included ambulances volantes (“flying ambulances”) and the principle of prioritising the most urgent cases which laid the foundations for modern triage, emergency evacuation, and trauma care.

Larrey performed thousands of amputations, often within minutes of injury, defying prevailing surgical dogma that delayed intervention. He carefully documented the outcomes of early versus late amputation, arguing that prompt surgery saved lives. His observations of cold injury during the disastrous retreat from Moscow provided some of the earliest insights into frostbite and rewarming. He also broke ground in thoracic surgery, describing drainage of empyemas, haemothorax, and pericardiotomy.

Larrey’s humanity became as famous as his surgical skill. He treated friend and foe alike, working under fire to rescue the wounded. Soldiers revered him, passing him hand-to-hand across the Berezina while crying “Save our saviour!” Napoleon named him in his will as “the most virtuous man I have ever met.” Even his enemies respected him. Wellington is said to have ordered a cease-fire to allow him to continue his work at Waterloo, and Blücher released him after capture in gratitude for care given to his son. Larrey embodied a new model of the military surgeon; scientific, humane, and indispensable.

Biographical Timeline

- Born July 8, 1766 at Beaudean, Hautes-Pyrénées, France.

- 1783 – Moves to Paris at 17; apprentices under his uncle Alexis Larrey, chief surgeon at Hôtel-Dieu in Toulouse.

- 1787 – Completes medical studies in Paris; joins French Navy as ship’s surgeon on the frigate La Vigilante during voyage to Newfoundland and Canada.

- 1788–1792 – Returns to Paris to work at Hôtel des Invalides and studies under Pierre-Joseph Desault (1738-1795).

- 1792 – Enlists in French Revolutionary Army as surgeon.

- 1793 – Introduces the ambulance volante (“flying ambulance”), a mobile surgical unit for immediate battlefield care.

- 1794 – Participates in Battle of Fleurus, establishing reputation for skill and innovation.

- 1797–1798 Serves in Napoleon’s Italian Campaigns. Appointed chief surgeon of the Army of Italy.

- 1798–1801 Egyptian campaign with Napoleon. Conducts surgical practice under harsh conditions, writes detailed reports on tropical diseases.

- 1804 – Becomes Chirurgien en chef (Surgeon-in-Chief) of the Grande Armée.

- 1805–1807 Serves Napoleon at Ulm and Austerlitz. Refines battlefield triage and transport.

- 1806 – Officer of the Légion d’honneur (Jena).

- 1807 – Napoleon presents Larrey with his own sword for extraordinary service (Eylau)

- 1809 – Ennobled as Baron de Larrey after Battle of Wagram.

- 1812 – Performs under extreme conditions at Borodino and during retreat from Moscow.

- 1813 – Captured at the Battle of Leipzig. Reportedly recognized by the Prussian general, Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, who spared his life because Larrey had once treated his son.

- 1815 – At Waterloo, primary accounts describe Wellington ordering a temporary cease-fire so Larrey could evacuate wounded. Following Napoleon’s defeat, Larrey was briefly exiled to Italy/Brussels but allowed to return to France later that year.

- 1816 – Under the Bourbon Restoration, Larrey reinstated to the Légion d’honneur despite having been Napoleon’s surgeon.

- 1820s–1830s – Writes and publishes Mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagnes (5 vols., 1812–1817; extended later), documenting his surgical innovations and campaigns.

- 1829 – Appointed to French Academy of Medicine.

- Died July 25, 1842 in Lyon while returning from a health cure in the Alps. Napoleon had famously declared: “If ever the army erects a monument to a man who has been the most devoted and the most selfless, it should be to Larrey.”

Key Medical Contributions

Flying ambulances and Triage

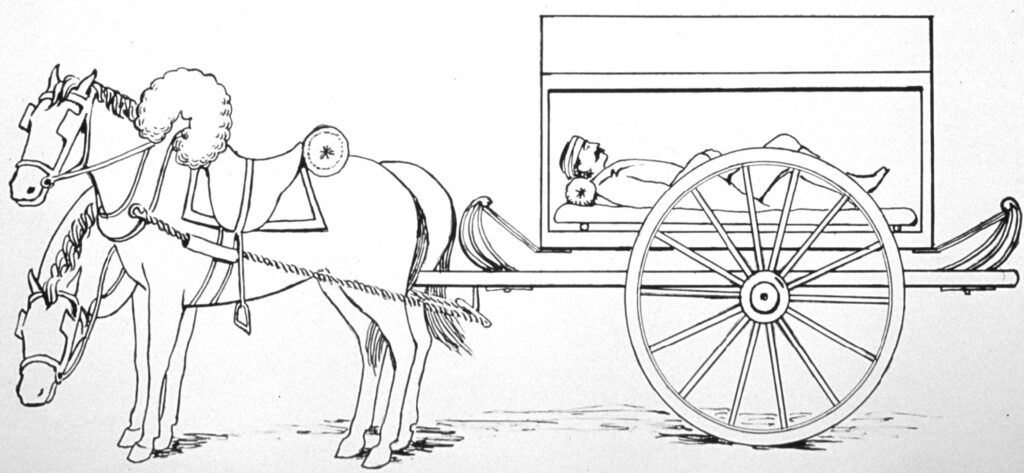

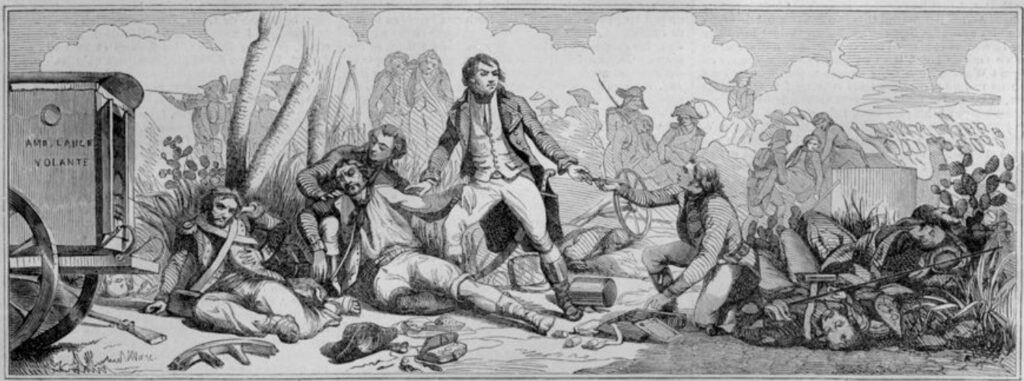

Larrey conceived the ambulance volante in 1792 after seeing men die for lack of timely care. His wagons carried surgeons, supplies, and litters directly onto the battlefield, reducing delays from 24–36 hours to about an hour.

On laissait les blessés sur le champ de bataille jusqu’après le combat, puis on les réunissait dans un local favorable où l’ambulance se rendait aussi promptement qu’il était possible; mais la quantité d’équipages interposés entre elle et l’armée, et beaucoup d’autres difficultés la retardaient au point qu’elle n’arrivait jamais avant vingt-quatre heures, quelquefois même trente-six heures et davantage; en sorte que la plupart des blessés périssaient faute de secours. La prise de Spire nous en ayant donné un assez grand nombre, j’eus la douleur d’en voir mourir plusieurs, victimes de cet inconvénient; ce qui me donna l’idée d’établir une nouvelle ambulance qui fût en état de porter de prompts secours sur le champ de bataille même. Il ne me fut possible d’exécuter ce projet que quelque temps après. – Larrey, 1812

The wounded were left on the battlefield until after the combat, then gathered in a suitable place where the ambulance arrived as soon as possible; but the number of convoys interposed between it and the army, and many other difficulties, delayed it so much that it never arrived before twenty-four hours, sometimes even thirty-six hours or more. Thus most of the wounded perished for lack of assistance. The capture of Speyer (1792) provided us with a large number of such cases, and I had the sorrow of seeing many die, victims of this defect. This gave me the idea of establishing a new ambulance capable of bringing prompt aid on the battlefield itself. It was only some time later that I was able to carry this project into execution. – Larrey, 1812

Ce fâcheux contre-temps me détermina à proposer au général en chef et au commissaire général Villemansy, plein de zèle et de sollicitude pour cette classe d’infortunés, l’établissement d’une ambulance capable de suivre tous les mouvemens de l’avant-garde, à l’instar de l’artillerie volante. Ma proposition fut acceptée, et je fus autorisé à organiser cette ambulance, que je nommai ambulance volante. J’avais d’abord imaginé de faire porter les blessés sur des chevaux garnis de bâts et de paniers convenables, mais l’expérience me fit bientôt connaître l’insuffisance et l’inutilité de ce moyen. Je conçus alors un système de voiture suspendue, qui pût réunir à la solidité, la célérité et la légèreté. Je donnerai la description de cette ambulance dans ma campagne d’Italie de l’an V (1797), où je l’avais déjà portée au degré de perfection qu’elle a aujourd’hui – Larrey 1812

This unfortunate mishap led me to propose to the general-in-chief and to Commissary General Villemansy—so zealous and solicitous for this class of unfortunates—the establishment of an ambulance capable of following all the movements of the vanguard, in the manner of the flying artillery. My proposal was accepted, and I was authorized to organize this ambulance, which I named the flying ambulance. At first I had imagined carrying the wounded on horses equipped with saddles and suitable panniers, but experience soon showed me the insufficiency and uselessness of this method. I then conceived of a suspended carriage system, which could combine solidity, speed, and lightness. I shall give the description of this ambulance in my Italian campaign of Year V (1797), where I had already brought it to the degree of perfection it possesses today. – Larrey 1812

Triage

Larrey is often hailed as the “father of modern triage,” though the term itself never appears in his writings. In his Mémoires de chirurgie militaire, he repeatedly emphasised that the most urgent wounds demanded priority, regardless of rank or nationality. He decried the old practice where officers were always treated first while soldiers died unattended, recalling instead:

1803 – In Relation historique et chirurgicale de l’expédition de l’armée d’Orient, Larrey contrasted older practices where the wounded were left to perish until after combat, with his innovation of ambulances capable of providing immediate aid on the battlefield itself:

“On laissait les blessés sur le champ de bataille jusqu’après le combat… en sorte que la plupart des blessés périssaient faute de secours. … Ce qui me donna l’idée d’établir une nouvelle ambulance qui fût en état de porter de prompts secours sur le champ de bataille même.”

Larrey, 1803

(“The wounded were left on the battlefield until after the combat … so that most of them perished for lack of assistance. … This gave me the idea of establishing a new ambulance, capable of providing immediate aid on the battlefield itself.”)

1812 – Later, in his Mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagnes, he emphasised that treatment should follow medical urgency alone:

“Je m’empressais de panser les blessés les plus gravement atteints, sans m’arrêter à leur grade; souvent les simples soldats recevaient les premiers secours avant les officiers, lorsque leurs blessures les mettaient en plus grand danger.”

(“I hastened to dress the most severely wounded, without regard to their rank; often the common soldiers received the first aid before the officers, when their wounds placed them in greater danger.”)

Larrey thus pioneered triage in practice: rapid battlefield assessment, immediate evacuation with his ambulances volantes, and treatment by need rather than privilege. Yet he never used the verb trier or the noun triage. The word drifted in later, applied retrospectively. By the mid-19th century, French military writers such as Sanson (1836) and Valette (1858) were describing Larrey’s method explicitly as “le triage des blessés”, formalising a phrase he himself never coined.

1854-1856 – The first fully systematised triage scheme is attributed to Nikolai Pirogov (1810-1881) during the Crimean War. Working with the Sisters of Mercy at Sebastopol, he divided the wounded into four categories transformed Larrey’s principle into a graded protocol

- Moribund patients needing only comfort;

- Those requiring urgent surgery;

- Those whose operations could be delayed;

- Those with minor injuries suitable for rapid evacuation.

The word triage itself only became institutionalised during World War I, when French field hospitals at Verdun (1916) established sections de triage. By then the term had entered official military vocabulary, completing the evolution:

- Larrey (principle and practice, 1790s–1810s)

- Pirogov (formal categorisation, 1850s)

- WWI (institutional adoption of the word triage).

Amputation and Surgical Skill

Dominique-Jean Larrey transformed the surgical management of battlefield injuries by advocating early, decisive amputation. While most surgeons delayed operations for days, believing patients needed time to regain strength, Larrey argued that the safest moment was within the first 24 hours. From his observations in the Napoleonic campaigns, he reported:

Quarante-cinq amputations de bras, d’avant-bras, de cuisses et de jambes furent pratiquées en ma présence par les chirurgiens-majors de nos ambulances légères. Toutes les opérations faites dans les premières vingt-quatre heures ont été généralement suivies de succès ; celles au contraire qui n’ont été pratiquées que les troisième, quatrième ou cinquième jours, n’ont pas aussi bien réussi. Cette différence a été connue et observée par tous les chirurgiens des armées, et il ne peut rester aucun doute sur la nécessité de faire l’amputation sur-le-champ, lorsqu’elle est indiquée…Dans cette circonstance, l’homme de l’art fat son devoir, et ne songe point à sa réputation…In this circumstance, the skilled surgeon does his duty and does not consider his reputation. – Larrey, 1812

Forty-five amputations of arms, forearms, thighs, and legs were performed in my presence by the senior surgeons of our light ambulances. All operations performed within the first twenty-four hours were generally successful; those, on the contrary, performed only on the third, fourth, or fifth days were not as successful. This difference has been known and observed by all army surgeons, and there can be no doubt about the necessity of performing amputation immediately when indicated….In this circumstance, the skilled surgeon does his duty and does not consider his reputation. – Larrey, 1812

Through thousands of procedures performed in the Napoleonic campaigns, Larrey refined his technique, emphasising speed, thorough debridement, and humane decisiveness. He justified the practice on both scientific and ethical grounds:

Quelque cruelle que puisse être une opération, elle est un acte d’humanité entre les mains du chirurgien, dès qu’elle peut sauver les jours d’un blessé, qui sont en danger ; et plus le danger est grand et pressant, plus les secours doivent être prompts et énergiques – Larrey, 1812

However cruel an operation may be, it is an act of humanity in the hands of the surgeon, as soon as it can save the life of a wounded person who is in danger; and the greater and more pressing the danger, the more prompt and energetic the assistance must be – Larrey, 1812

Larrey framed amputation not as a last resort, but as a humane duty when it offered the only chance of survival. His principles prefigured modern trauma care, where the timing of intervention is often as critical as the operation itself.

Cold Injury and Therapeutic Hypothermia

During Napoleon’s campaigns, especially the freezing conditions of Russia, Larrey observed the effects of extreme cold on soldiers and developed insights into both its pathology and treatment. He was one of the first to articulate both the dangers of rapid rewarming and the therapeutic potential of hypothermia.

Larrey noted that it was not the extreme cold itself, but the sudden application of heat to frozen tissues that precipitated gangrene. Soldiers who warmed themselves rapidly by the fire were the most affected, whereas gradual rewarming could preserve life and limb. His advice anticipated modern staged rewarming and included snow-rubbing followed by the application of des lotions spiritueuses et camphrées.

Experience proves that gangrene from frostbite may be averted by taking care not to approach a fire, or to be subjected to the sudden action of heat on the parts benumbed by the cold. All this proves that cold is only the predisposing cause of the gangrene. Heat suddenly applied to the parts which have been rendered torpid by cold, may be considered as the exciting cause.

Larrey, 1814 (Vol II translation)

Larrey recognised that cold could play a protective role. He observed that soldiers with frozen limbs experienced little pain during amputation, and bleeding was markedly reduced. He advocated the controlled use of cold and ice as a form of natural anaesthesia and a means of limiting surgical shock. Larrey noted that tissues could endure a period of ‘asphyxia’ from cold, provided that rewarming was gradual and stepwise.

The parts may remain for a longer or shorter period of asphyxia without losing their life; and if the cold be removed by degrees, or if the person affected by it pass gradually into a more elevated temperature, the equilibrium may be easily re-established with the function of the organs

Larrey, 1814

Thoracic and Pericardial Interventions

Larrey is remembered as a pioneer of thoracic surgery, yet he was not the first to enter the pericardium.

1801 – the Spanish surgeon Francisco Romero performed the earliest documented pericardiotomy. Several of his patients survived his drainage of both pericardial and pleural effusions. In his 1815 Latin memoir he proudly declared: “Novum posteritati sanitatis condidi signum, anno 1801” (“I have established a new medical landmark for posterity, in the year 1801”).

1810 – Larrey reported one of the most famous early pericardial operations. His patient, Bernard Saint-Ogne, an ex-soldier with a chest wound, developed severe pericardial effusion. In his Notice sur une blessure du péricarde, suivie d’hydropéricardie (1810) he described cutting beneath the left nipple and evacuating half a litre of rust-coloured fluid mixed with blood clots. He improvised a rudimentary drain with a probe, and the patient survived.

Je pratiquai une incision oblique sous le mamelon gauche… et j’ouvris le péricarde qui était distendu. Il s’en échappa près d’une livre de liquide rougeâtre, d’une couleur rouille, qui comprimait le cœur et gênait ses mouvements. Je plaçai un morceau de linge pour donner issue aux matières, et le malade se rétablit peu à peu. – Larrey 1810

I made an oblique incision under the left nipple… and opened the distended pericardium. Nearly a pound [≈ 0.5 liters] of reddish, rust-coloured fluid escaped, which had been compressing the heart and hindering its motion. I placed a piece of cloth to allow further drainage, and the patient gradually recovered – Larrey 1810

1829 – Larrey went on to perform multiple cadaveric experiments and published des plaies du péricarde et du coeur in which he emphasised thoracic access routes and the feasibility of evacuating pericardial fluid without immediate death.

Larrey also published De la hernie congéniale , in which he described congenital diaphragmatic hernias, with special focus on the anterior parasternal defect. This type of defect would later be distinguished as the foramen of Larrey (anterior/left parasternal hernia), in contrast to the foramen of Morgagni (right parasternal hernia).

Humanity Under Fire

Larrey was revered not only for his surgical skill but for his impartial humanity. He treated French and enemy soldiers alike, often operating under fire. His reputation was such that friend and foe alike went out of their way to protect him.

The Berezina (1812): During Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, soldiers are said to have cried “Sauvez notre sauveur !” (“Save our savior!”) as they passed Larrey over their heads across the bridge, ensuring his escape

Waterloo (1815): Several accounts report that the Duke of Wellington ordered a cease-fire in Larrey’s vicinity so that he could continue tending the wounded, and that Blücher, after capture, released him in recognition of care previously given to his son

Napoleon’s will (1821): In exile on Saint Helena, Napoleon dictated: “Il est l’homme le plus vertueux que j’aie jamais connu“

Larrey. (Baron chirurgien en chef). Paroles de Napoléon, éloge; tous les blessés étaient ses enfans. Nommé par Napoléon dans son testament “l’homme le plus vertueux qu’il lût rencontré“

Larrey. (Baron, chief surgeon). Napoleon’s words; all the wounded were his children. Named by Napoleon in his will as “the most virtuous man he had met“

Major Publications

- Larrey DJ. Metodo per la cura del morbo epizootico regnante e per la preservazione dallo stesso del Cittadino. 1797

- Larrey DJ. Dissertation sur les amputations des membres, à la suite des coups de feu. 1803

- Larrey DJ. Relation historique et chirurgicale de l’expédition de l’armée d’Orient. 1803

- Larrey DJ. Notice sur une blessure du péricarde, suivie d’hydropéricardie. Bulletin des sciences médicales, 1810; 6: 255-273.

- Larrey DJ. Mémoires de chirurgie militaire, et campagnes. 1812 Vol II, Vol III, Vol IV.

- Larrey DJ. Memoirs of military surgery: and campaigns of the French armies. 1814 Vol II

- Larrey DJ. Traité de la maladie scrophuleuse : ouvrage couronné par l’Académie impériale des curieux de la nature. 1821

- Larrey DJ. Considerations sur la fièvre jaune. 1821

- Larrey DJ. On the use of the moxa, as a therapeutical agent. 1822

- Larrey DJ. Surgical essays. 1823

- Larrey DJ. Clinique chirurgicale : exercée particulièrement dans les camps et les hopitaux militaires, depuis 1792 jusqu’en 1829. 1829 Vol II. Vol III, Vol IV.

- Larrey DJ. Mémoire sur le choléra-morbus. 1831

- Larrey DJ. Surgical memoirs of the campaigns of Russia, Germany, and France. 1832

- Larrey DJ. Observations on wounds, and their complications by erysipelas, gangrene and tetanus, and on the principal diseases and injuries of the head, ear and eye. 1832

References

Biography

- Werner H. Jean Dominique Larrey : ein Lebensbild aus der Geschichte der Chirurgie. 1885

- Da Costa JC. Baron Larrey: a Sketch, Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp 1906; 17: 195-215.

- Bechet PE. Jean Dominique Larrey: A Great Military Surgeon. Ann Med Hist. 1937 Sep;9(5):428-436.

- Turner MD, Shah MH. Dominique-Jean Larrey (1766-1842): The Founder of the Modern Triage System. Cureus. 2024 Jun 14;16(6):e62375

Eponymous terms

- Baron Larrey’s Ambulance, 1797

- Brewer LA 3rd. Baron Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842). Father of modern military surgery, innovater, humanist. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1986 Dec;92(6):1096-8.

- Howard MR. In Larrey’s shadow: transport of British sick and wounded in the Napoleonic wars. Scott Med J. 1994 Feb;39(1):27-9

- Burris DG, Welling DR, Rich NM. Dominique Jean Larrey and the principles of humanity in warfare. J Am Coll Surg. 2004 May;198(5):831-5.

- Baker D, Cazalaà JB, Carli P. Resuscitation great. Larrey and Percy–a tale of two barons. Resuscitation. 2005 Sep;66(3):259-62.

- Pearce R. Historical developments in casualty evacuation and triage JMVH 2005; 14(2)

- Robertson-Steel I. Evolution of triage systems. Emerg Med J. 2006 Feb;23(2):154-5.

- Skandalakis PN, Lainas P, Zoras O, Skandalakis JE, Mirilas P. “To afford the wounded speedy assistance”: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon. World J Surg. 2006 Aug;30(8):1392-9.

- Wood MM. Dominique-Jean Larrey, chief surgeon of the French Army with Napoleon in Egypt: notes and observations on Larrey’s medical memoirs based on the Egyptian campaign. Can Bull Med Hist. 2008;25(2):515-35.

- Varon J, Acosta P. Therapeutic hypothermia: past, present, and future. Chest. 2008 May;133(5):1267-74.

- Remba SJ, Varon J, Rivera A, Sternbach GL. Dominique-Jean Larrey: the effects of therapeutic hypothermia and the first ambulance. Resuscitation. 2010 Mar;81(3):268-71.

- Welling DR, Burris DG, Rich NM. The influence of Dominique Jean Larrey on the art and science of amputations. J Vasc Surg. 2010 Sep;52(3):790-3.

- Ferrandis JJ, Lefort H, Tabbagh X, Pons F. Le triage des blessés pendant la Grande Guerre [War casualty triage during the First World War]. Soins. 2014 Jun;(786):41-5.

- Ramdhan RC, Rai R, Brooks KN, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Tubbs RS. Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842) and His Contributions to Military Medicine and Early Neurosurgery. World Neurosurg. 2018 Dec;120:96-99.

- Knight RM, Moore CH, Silverman MB. Time to Update Army Medical Doctrine. Mil Med. 2020 Sep 18;185(9-10):e1343-e1346.

- Ellis H. Dominique Jean Larrey, gunshot wounds of the bladder. J Perioper Pract. 2022 May;32(5):131-132.

- Karamouzis K, Perdikakis M, Michaleas SN, Karamanou M. Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey (1766-1842): innovator of the triage. Acta Chir Belg. 2024 Feb;124(1):66-72

Eponym

the person behind the name

MBChB, BMedSci in Global Health and Health Policy, University of Edinburgh. Currently working in the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Australia. Career focus is emergency medicine, with interests in humanitarian and pre-hospital care and treatment difficulties faced in resource-limited settings.

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |