Error in Research

OVERVIEW

- error in research can be systematic or random

- systematic error is also referred to as bias

TYPES

Random error

- error introduced by a lack of precision in conducting the study

- defined in terms of the null hypothesis, which is no difference between the intervention group and the control group

- reduced by meticulous technique and by large sample size

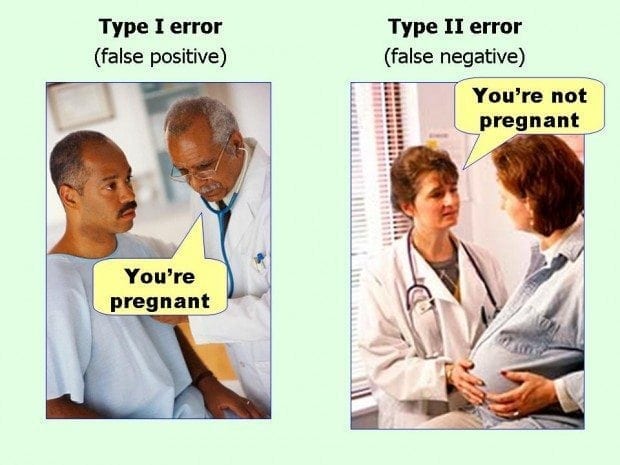

Type 1 error

- ‘false positive’ study

- the chance of incorrectly rejecting the null hypothesis (finding a difference which does not exist)

- the alpha value determines this risk

- alpha (ɑ) is normally 0.05 (same as the p-value or 95% confidence interval) so there is a 5% chance of making a type 1 error

- the error may result in the implementation of a therapy that is ineffective

Type 2 error

- ‘false negative’ study

- the chance of incorrectly accepting the null hypothesis (not finding the difference, despite one existing)

- this risk is determined by (1 – beta)

- beta (𝛽) is normally 0.8 (this is the power of a study) so the chance of making a type 2 error is 20%

- may result in an effective treatment strategy/drug not being used

- Type I errors, also known as false positives, occur when you see things that are not there.

- Type II errors, or false negatives, occur when you don’t see things that are there

TECHNIQUES TO MINIMIZE ERROR

Prior to Study

- study type: a well constructed Randomised control trial (RCT) is the ‘gold standard’

- appropriate power and sample size calculations

- choose an appropriate effect size (clinically significant difference one wishes to detect between groups; this is arbitrary but needs to be:

— reasonable

— informed by previous studies and current clinical practice

— acceptable to peers

During Study

- minimise bias

- sequential trial design

— allows a clinical trial to be carried out so that, as soon as a significant result is obtained, the study can be stopped

— minimises the sample size, cost & morbidity - interim analysis

— pre-planned comparison of groups at specified times during a trial

— allows a trial to be stopped early if a significant difference is found

At Analysis Stage, avoid:

- use of inappropriate tests to analyze data

— e.g. parametric vs non-parametric, t-tests, ANOVA, Chi, Fishers exact, Yates correction, paired or unpaired, one-tailed or two-tailed

At Presentation, avoid:

- failure to report data points or standard error

- reporting mean with standard error (smaller) rather than standard deviation

- assumption that statistical significance is equivalent to clinical significance

- failure give explicit details of study and statistical analysis

- publication bias

References and Links

LITFL

Critical Care

Compendium

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC