Extraordinary Cries

aka Pulmonary Puzzler 010

A 13 year-old boy with a history of allergic rhinitis is sent in to the emergency department by his family doctor. Three days previously he was exposed to smoke from a bushfire and has been having difficult breathing since. He has been having sudden exacerbations where his chest and throat feels tight and he feels as though he can’t get any air in. There has been no improvement despite treatment with prednisolone and ventolin over the past 2 days.

In the emergency department he is tachypneic (RR26) but otherwise looks well and his other vital signs are within normal limits (including SpO2 99% OA). During examination you notice a loud inspiratory stridor.

Questions

Q1. What is the differential diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

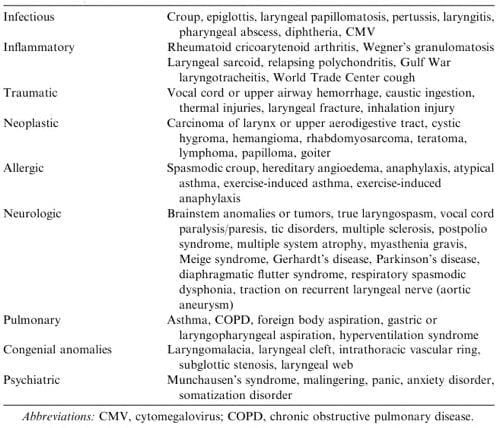

If you apply a pathophysiological sieve to the supraglottic, glottic and subglottic structures you might come with a list like this (!):

However, at least one important diagnosis is missing from the list shown above…

Q2. What investigations should be considered?

Answer and interpretation

Depending on the presentation and the setting, the following may be useful:

- Chest x-ray

- Pulmonary function tests

- flexible laryngoscopy

- videostroboscopy (used to assess vocal cord vibration by producing intermittent light flashes in close relation to the frequency of the vocal-fold vibration)

- laryngeal electromyography (EMG)

- calcium

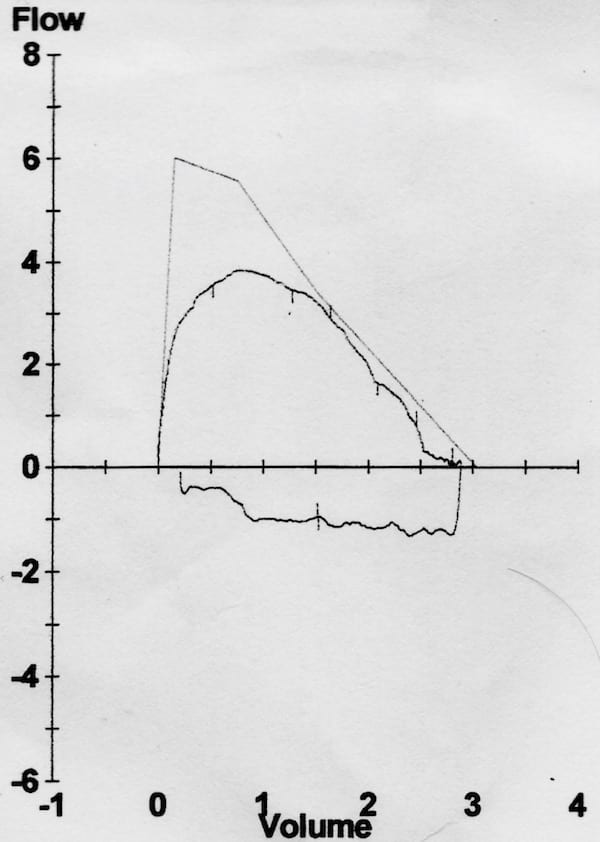

In this case a chest x-ray was performed, which was normal, and then lung function tests were performed. The following flow-volume loop was obtained:

Q3. What does the investigation shown in Q2 indicate?

Answer and interpretation

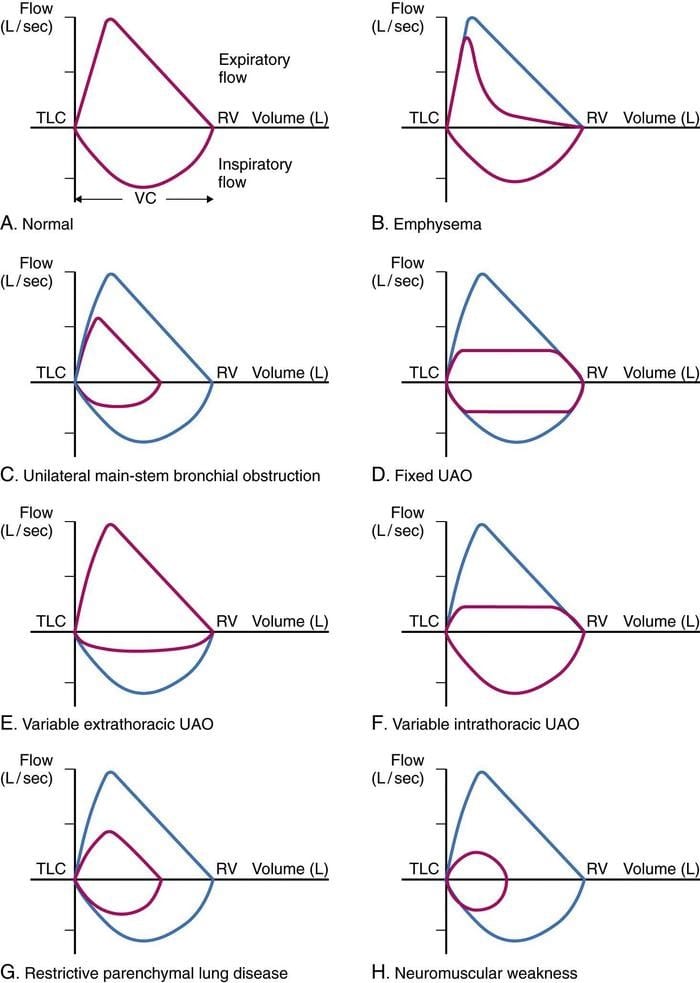

- The inspiratory flow curve is truncated or flattened, which is consistent with extrathoracic airway obstruction.

- The peak expiratory flow rate was less than predicted, although the downward slope approximates the predicted flow rate at lower flows.

- The expiratory pattern may be effort related, but is not too dissimilar from that seen in a fixed upper airway obstruction.

Q4. What investigation is likely to be most useful?

Answer and interpretation

Visualisation of the cords by laryngoscopy.

The ENT team were contacted and flexible laryngoscopy was performed.

- The vocal cords appeared normal and had normal movement.

- There was erythema of the arytenoids consistent with inflammation.

- The pharynx was normal.

- There were no foreign bodies visualised.

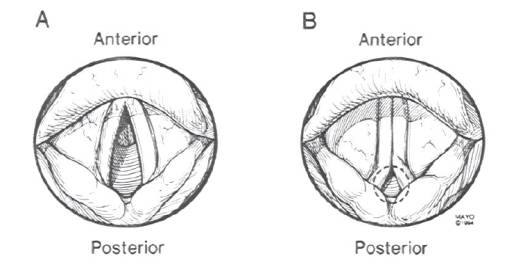

Here is a video of normally functioning vocal cords:

Q5. What is the likely diagnosis?

Answer and interpretation

Vocal cord dysfunction (VCD) aka paradoxical vocal cord motion (PVCM)

This refers to upper airway obstruction associated with the nonphysiologic, paradoxical adduction or closure of the true vocal folds on inspiration, with or without concomitant closure on expiration.

The lung-volume loop is consistent with this, but laryngoscopy did not confirm the finding. This is probably because the patient did not have stridor when laryngoscopy was performed — his symptoms had (temporarily?) resolved! However, even in asymptomatic patients VCD can still be visualised about 60% of the time, but not in this case.

The figure below shows the classic vocal cord appearances seen during inspiration with normal vocal cord motion (A) and with paradoxical vocal cord motion (B) — note the presence of ‘posterior chinking’ in the latter case.

There are over 70 names for this condition used in the literature, so you can imagine how evidence-based the treatment is…

Q6. How does this condition typically present?

Answer and interpretation

Clinical presentations vary from mild dyspnea to acute severe respiratory distress.

Symptoms include:

- sudden onset of difficulty breathing, usually on inhalation

- air hunger, choking, suffocating

- tightness localized to the throat or chest, chest pain

- cough, throat clearing

- difficulty swallowing, globus pharyngeus sensation (sensation of a lump in the throat)

- intermittent aphonia (loss of voice) or dysphonia (deviant vocal quality)

- fatigue

Signs include:

- stridor

- laryngeal wheezing

- neck or chest retractions

The acute presentation is frightening and may result in a panic attack. Alternatively, patients may exhibit no distress whatsoever yet complain of severe respiratory distress (“la belle indifference”).

An example of inspiratory stridor in a child:

Q7. What condition is this most commonly mistaken for?

Answer and interpretation

Asthma — in some studies well over half of all vocal cord dysfunction cases are misdiagnosed as asthma, for an average of about 5 years!

Both VCD and asthma can be exercise-induced, but VCD usually comes on during exercise whereas asthma tends to come in after exercise. Of course, the two conditions may coexist…

Check out this table (Features distinguishing paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder from asthma) showing the distinguishing features of these two conditions.

Clinicians and the parents of pediatric patients only agree on the identification of respiratory sound as wheeze about 50% of the time. Make sure you can distinguish inspiratory stridor from expiratory wheeze!

Q8. What factors may contribute to this condition?

Answer and interpretation

The pathophysiological mechanisms resulting in vocal cord dysfunction are uncertain.

Contributing factors may include:

- upper respiratory tract infection

- exercise

- laryngopharyngeal reflux (GORD) — treatement is not always effective

- irritant exposure

- allergic rhinitis with postnasal drip

- excessive voice demands (e.g. singing, drama, public speaking)

- stress, anxiety and mood disorders — e.g. including posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and panic attack (but some patients may have psychological disorders as a result of VCD)

- neuroleptics (acute dystonic reactions)

These factors may lead to VCD as a result of upper airway hyper-responsiveness (the “irritable larynx syndrome”), exaggeration of the glottic closure reflex, autonomic dysfunction affecting the larynx or by psychological mechanisms.

In this case, the arytenoid erythema noted might reflect irritation from the bushfire exposure, a recent upper respiratory tract infection or laryngopharyngeal reflux.

Q9. What are the management options?

Answer and interpretation

Acute management

- Reassure patient

- Instruct patient in breathing behaviors that help to overcome paradoxical vocal cord closure — panting (e.g. short, rapid breathing with an open mouth), diaphragmatic breathing, breathing through the nose or a straw, pursed-lip breathing, and/ or exhaling with a hissing sound

- Consider heliox in patients with persistent or severe vocal cord dysfunction

Chronic management

- Avoid known triggers, such as smoke, airborne irritants, or certain medications

- Treat underlying conditions, including anxiety, depression, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GORD), and rhinosinusitis

- Consider inhaled ipratropium, especially in patients with exercise-induced symptoms

- Referral for speech therapy is indicated in patients with unresolved symptoms (this is the mainstay of treatment for chronic symptoms)

- Long-term tracheostomy is rarely if ever needed

A description of this condition by Sir William Osler:

Spasm of the muscles may occur with violent inspiratory efforts and great distress, and may even lead to cyanosis. …Extraordinary cries may be produced, either inspiratory or expiratory.

Osler: Principles and practice of medicine. 1902 Vol II Ed 5 p1116

References

- Hicks M, Brugman SM, Katial R. Vocal cord dysfunction/paradoxical vocal fold motion. Prim Care. 2008 Mar;35(1):81-103, vii. PMID: 18206719.

- Ibrahim WH, Gheriani HA, Almohamed AA, Raza T. Paradoxical vocal cord motion disorder: past, present and future. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83(977):164-72PMC2599980.

- For more Pulmonary cases check out the LITFL Top 150 Chest X-Rays

- Osler W. Principles and practice of medicine. 1902 Vol II Ed 5 p1116

CLINICAL CASES

Pulmonary Puzzler

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC