Extremity arterial injury

Revised and reviewed 15 August 2015

OVERVIEW

- The extremities are the most common sites of arterial injuries in the civilian setting

- 50% to 60% of injuries occur in the femoral or popliteal arteries

- 30% in the brachial artery

- Extremity arterial injuries may be the result of blunt or penetrating trauma

- They may be threatening due to exsanguination, result in multi-organ failure due to near exsanguination or be limb threatening due to ischemia and associated injuries

TYPES OF VESSEL INJURY

There are 5 major types of arterial injury:

- intimal injuries (e.g. flaps, disruptions, or subintimal/intramural hematomas)

- complete wall defects with pseudoaneurysms or hemorrhage

- complete transections with hemorrhage or occlusion

- arteriovenous fistulas

- spasm

ASSESSMENT

General

- Penetrating extremity injury (e.g. stab or gunshot) or severe blunt trauma (e.g. arterial injury due to associated fracture)

- Cold, pale and pulseless distal extremity or a rapidly expanding hematoma suggests arterial compromise — look for ‘hard signs’and ‘soft signs’

- Check arterial pressure index (API)

- Assess for hemorrhagic shock

- Angiography can be performed only if the patient is hemodynamically stable

- Pulses and APIs may be difficult to assess in the obese, shocked, hypothermic or those with pre-existing peripheral vascular disease

Hard signs

- Absent pulses

- Bruit or thrill

- Active or pulsatile hemorrhage

- Signs of limb ischemia/ compartment syndrome (the 6 Ps)

- Pulsatile or expanding hematoma

Soft signs

- Proximity of injury to vascular structures

- Major single nerve deficit (e.g. sciatic, femoral, median, ulna or radial)

- Non-expanding hematoma

- Reduced pulses

- Posterior knee or anterior elbow dislocation

- Hypotension or moderate blood loss at the scene

Arterial pressure index (API)

- also known as DPI (Doppler Pressure Index) or Arterial Brachial Index or Ankle Brachial Index (ABI) – despite the last name, the same procedure can be performed for upper extremity injuries

- The procedure is performed as follows for an injured upper extremity:

- The patient is placed supine with the cuff placed on the injured upper extremity

- The ipsilateral brachial artery is detected with a Doppler device until the brachial artery is clearly heard. Alternatively the cuff can be placed on the forearm and the ulnar or radial arteries are assessed (the cuff has to be distal to the injury!).

- The cuff is pumped up 20 mmHg past the point where the Doppler sound disappears. The cuff is slowly released until the Doppler device picks up the arterial sound again (the systolic pressure)

- The pressure at which this sound occurs is recorded and the procedure is repeated for the opposite uninjured upper extremity.

- It can also be performed for an injured lower extremity:

- The patient is placed supine with the cuff placed on the injured lower extremity.

- The ipsilateral dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial artery is detected with a Doppler device until the artery is clearly heard

- The cuff is pumped up 20 mmHg past the point where the Doppler sound disappears. The cuff is slowly released until the Doppler device picks up the arterial sound again (the systolic pressure)

- The pressure at which this sound occurs is recorded and the procedure is repeated for the opposite uninjured lower extremity

- The blood pressure is also measured at the brachial artery in an uninjured upper extremity.

- API = Injured SBP / Uninjured brachial SBP

- i.e. API = the systolic pressure of the injured extremity (ankle or forearm) divided by the brachial systolic pressure in the uninjured upper extremity

- API > 0.9 is highly unlikely to have a vascular injury and may be observed/ discharged depending on the nature of any other injuries, premorbid and social factors.

- API < 0.9 indicates possible vascular injury: requires further evaluation, preferably by computed tomography angiogram (CTA). Doppler ultrasound (50-100% sensitive, 95% specific) can be used as an alternative, and surgeons can perform intraoperative angiograms under fluoroscopy.

- Utility of API

- The performance characteristics of API vary between studies, but is quoted as 95% sensitive and 97% specific for arterial injury by Lynch and Johannsen (1991). In a small prospective study of knee dislocations ABI was 100% sensitive and specific (Mills et al, 2004). It is also cost effective (Levy et al, 2005).

- API will miss non-obstructing vascular injuries and will give false positive results in patients with shock or elderly patients with significant peripheral vascular disease. Some trauma centers use a difference in API of >=0.1 as an indication of arterial injury in elderly patients and those with known pre-existing peripheral vascular disease.

MANAGEMENT

Overview

- Employ the general approach to management of a trauma patient with significant extremity injuries (see Extremity Injuries)

- Immediate surgical consult

- Apply direct pressure and elevation +/- pressure bandaging

- Consider applying adrenaline soaked gauze or hemostatic dressings if available

- Tourniquets may be life saving

- Relocate any dislocations, reduce and splint long bone fractures, apply a pelvic binder for pelvic fractures

- Correct coagulopathy and commence hemostatic resuscitation as required

- Do not clamp or tie off a vessel in a bleeding wound, unless it is superficial and clearly visible. Blindly clamping an artery may damage a nerve that often runs alongside the artery

- Determine if definitive interventions are required for arterial repair

- Note that bleeding points proximal to these transition points cannot be controlled by externally applied direct pressure or tourniquets and require urgent surgical intervention:

- Femoral artery at the inguinal ligament

- Axillary artery as it emerges from under the clavicle

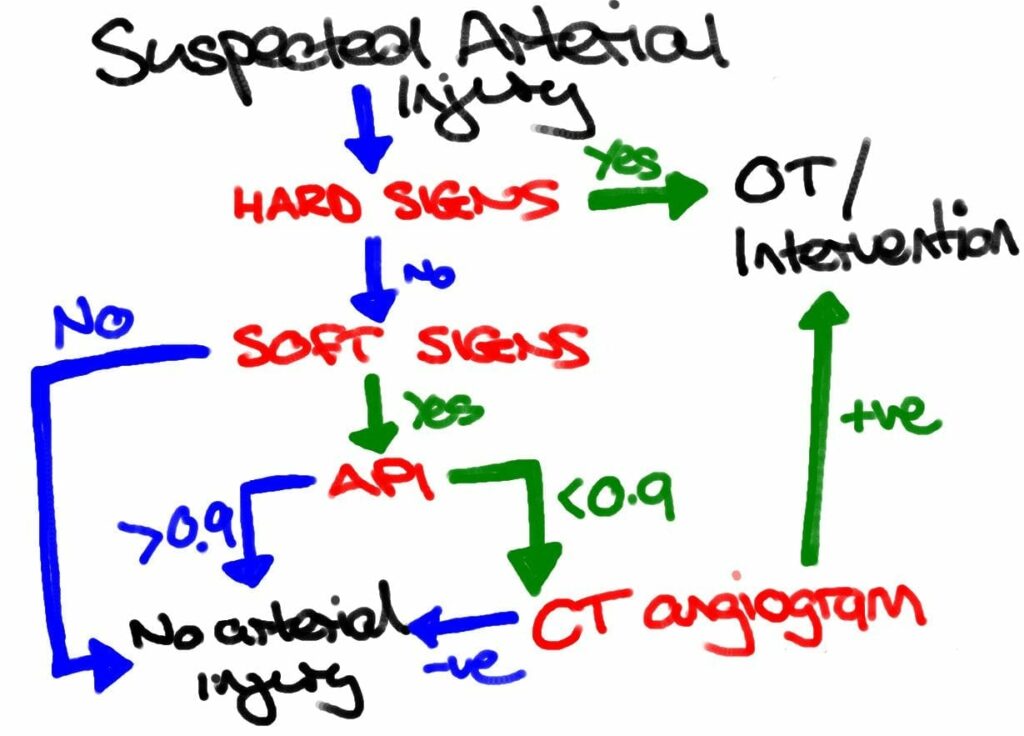

Approach to investigation of arterial injuries requiring definitive interventions for repair

- immediate operation on the injured extremity is usually appropriate in the patient without other life-threatening injuries if:

- “hard signs’ are present, or

- there is presence of extravasation, an acute pulsatile hematoma or early pseudoaneurysm, occlusion, or an arteriovenous fistula,

- UNLESS the following vessels are injured: profunda femoris artery, or proximal to the anterior tibial artery and tibioperoneal bifurcation in the leg

- Exceptions and clarifications to the above flow diagram based on the WEST guidelines (Feliciano et al, 2011):

- CTA may be performed in the presence of hard signs if there is a shot gun injury or multiple fractures to help localise the vascular injury before operating

- hemodynamically stable patients with hard signs with a presumed wall defect or occlusion of a named artery (i.e., doralis pedis pulse is absent, but foot is clearly well perfused) or clinical signs of an arteriovenous fistula in the distal two third of the leg should undergo diagnostic imaging and possible therapeutic embolization versus nonoperative management (a repeat arteriogram or duplex ultrasonography is performed 3 days to 5 days later in patients with occlusion)

- in some centers formal arteriography or duplex ultrasongraphy may be used in preference to multirow helical CTA, and surgeon-performed angiography can take place in the OT

- vasospasm can be managed with serial imaging and intra-arterial adminstration of vasodilators (e.g. paparavine, heparin and tolazoline, nitroglycerin and nifedipine.

- CTA may be required if pulses or API cannot be adequately assessed in the haemodynamically stable patient

Disposition

- significant arterial injuries require admission for interventions

- those with major haemorrhage or concomitant injuries or comorbidities may require HDU/ ICU admission

- patients discharged following a normal API require close outpatient follow up because 1-4% of these patients, primarily those with penetrating wounds, eventually require an operation as the original undetected injury (i.e. small pseudoaneurysm) progresses rather than heals

DIRECT PRESSURE

Direct digital pressure is the best method initially

- Employ universal precautions (wear sterile gloves, goggles and gown)

- Ensure there are no hazardous objects in the wound

- Use one finger, with interposed gauze, to press directly on the bleeding vessel just proximal to the bleeding point

- Maintain this for 10 minutes

Pressure bandages

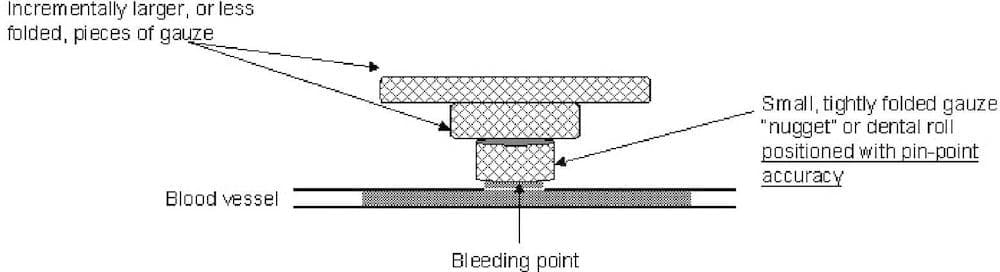

- The ‘nugget method’ described by Shokrollahi et al (2008) is effective

- The occluding finger should be substituted with a dental roll or tightly folded “nugget” of gauze.A tourniquet may be temporarily applied proximally to facilitate this.

- Once the positioning is correct and no further bleeding is occurring, slightly larger or less folded pieces of gauze can be placed one on top of the other, creating an inverted pyramid of gauze.

- The layers of gauze are secured with a loose bandage. Only very light pressure need be applied to the top layer of gauze to maintain hemostasis, as the pressure is “focused” onto the bleeding point. This technique is based on the equation: Pressure=Force/Area

- The tightness of the bandage can be judged from the amount of pressure needed to maintain haemostasis when applying the top layer of gauze.

TOURNIQUETS

The easiest way in the ED is to apply a blood pressure cuff proximal to the bleeding point

- Inflate the cuff above systolic blood pressure

- Clamp the tubing with a hemostat to prevent leakage and loss of pressure

An alternative is to use a pneumatic cuff, like that used for Bier’s blocks.

When applying a tourniquet ensure the following:

- Record the time of application

- Perform a neurological exam at the time of application

- Do not leave the tourniquet on for more than 120 minutes

INTERVENTIONS AND REPAIR OF DAMAGED VESSELS

Injuries to most major ‘named’ arteries requiring repair or intervention include:

- extravasation

- pulsatile hematoma

- occlusion

- pseudoaneurysm

- fistula formation

Techniques for repair of damaged vessels:

- Direct repair — sutures, patch angioplasty, interposition graft or vein patches

- Ligation — only small, distal and redundant arteries (most are repaired)

- Damage control surgery using temporary intravascular shunts to allow immediate restoration of distal blood flow, with later definitive repair once the patient has been resuscitated and normal physiology has resumed

- Interventional radiology measures such as embolisation are also useful in certain arterial injuries

Injuries that do not usually need immediate intervention:

- Some injuries, such as intimal defects (87-95% heal spontaneously), usually do not require intervention

- Some arteries (profunda femoris, anterior tibial, posterior tibial, or peroneal arteries) do not require surgery but can be re-imaged at 3-5 days to check progress if occluded, or undergo embolisation if the injury involves extravasation or arteriovenous fistula

References and Links

LITFL

- CCC — Extremity Injuries

Textbooks and Journal Articles

- Conrad MF, Patton JH Jr, Parikshak M, Kralovich KA. Evaluation of vascular injury in penetrating extremity trauma: angiographers stay home. Am Surg. 2002 Mar;68(3):269-74. PubMed PMID: 11893106.

- Feliciano DV, Moore FA, Moore EE, West MA, Davis JW, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, McIntyre RC Jr. Evaluation and management of peripheral vascular injury. Part 1. Western Trauma Association/critical decisions in trauma. J Trauma. 2011 Jun;70(6):1551-6. PubMed PMID: 21817992.

- Fildes J, et al. Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual (8th edition), American College of Surgeons 2008.

- Inaba K, Potzman J, Munera F, McKenney M, Munoz R, Rivas L, Dunham M, DuBose J. Multi-slice CT angiography for arterial evaluation in the injured lower extremity. J Trauma. 2006 Mar;60(3):502-6; discussion 506-7. PubMed PMID: 16531846.

- Inaba K, Branco BC, Reddy S, Park JJ, Green D, Plurad D, Talving P, Lam L, Demetriades D. Prospective evaluation of multidetector computed tomography for extremity vascular trauma. J Trauma. 2011 Apr;70(4):808-15. PubMed PMID: 21610388.

- Kragh JF Jr, Walters TJ, Baer DG, Fox CJ, Wade CE, Salinas J, Holcomb JB. Practical use of emergency tourniquets to stop bleeding in major limb trauma. J Trauma. 2008 Feb;64(2 Suppl):S38-49; discussion S49-50. PubMed PMID: 18376170.

- Legome E, Shockley LW. Trauma: A Comprehensive Emergency Medicine Approach, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Levy BA, Zlowodzki MP, Graves M, Cole PA. Screening for extremity arterial injury with the arterial pressure index. Am J Emerg Med. 2005 Sep;23(5):689-95. Review. PubMed PMID: 16140180.

- Lynch K, Johansen K. Can Doppler pressure measurement replace “exclusion” arteriography in the diagnosis of occult extremity arterial trauma? Ann Surg. 1991 Dec;214(6):737-41. PubMed PMID: 1741655; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1358501.

- Lundin M, Wiksten JP, Peräkylä T, Lindfors O, Savolainen H, Skyttä J, Lepäntalo M. Distal pulse palpation: is it reliable? World J Surg. 1999 Mar;23(3):252-5. PubMed PMID: 9933695.

- Marx JA, Hockberger R, Walls RM. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (7th edition), Mosby 2009. [mdconsult.com]

- Mills WJ, Barei DP, McNair P. The value of the ankle-brachial index for diagnosing arterial injury after knee dislocation: a prospective study. J Trauma. 2004 Jun;56(6):1261-5. PubMed PMID: 15211135.

- Shokrollahi K, Sharma H, Gakhar H. A technique for temporary control of hemorrhage. J Emerg Med. 2008 Apr;34(3):319-20. Epub 2007 Dec 27. PubMed PMID: 18164163.

- Newton EJ, Love J. Acute complications of extremity trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007 Aug;25(3):751-61, iv. PMID: 17826216.

FOAM and Web Resources

- Broome Docs — Clinical Case 018: Life and limb (not life OR limb)

- ScanCrit — The Mother of All Tourniquets (abdominal aorta tourniquet!)

- The Trauma Professional’s Blog — Using CT To Diagnose Extremity Vascular Injury

- The Trauma Professional’s Blog — Penetrating Injuries to the Extremities

Critical Care

Compendium

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at The Alfred ICU, where he is Deputy Director (Education). He is a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University, the Lead for the Clinician Educator Incubator programme, and a CICM First Part Examiner.

He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives. He was one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) has been recognised for his contributions to education with awards from ANZICS, ANZAHPE, and ACEM.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Bluesky, he is @precordialthump.bsky.social and on the site that Elon has screwed up, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC