Fifth disease

Erythema infectiosum

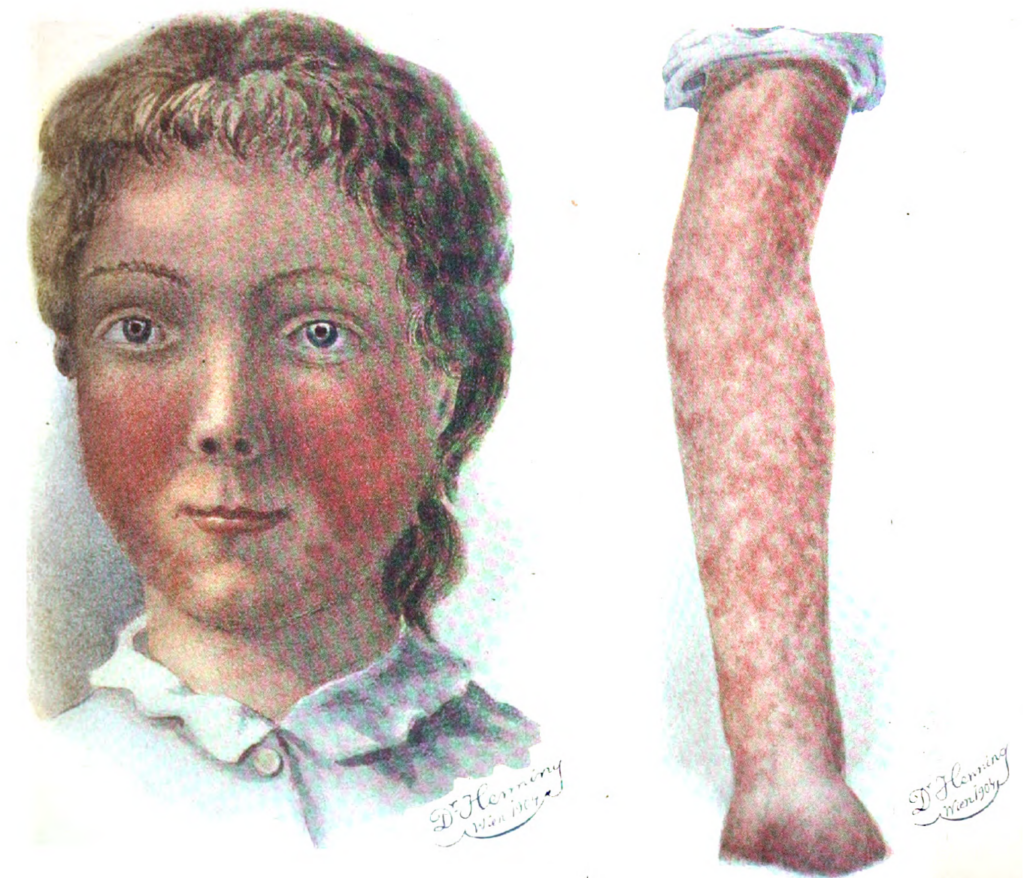

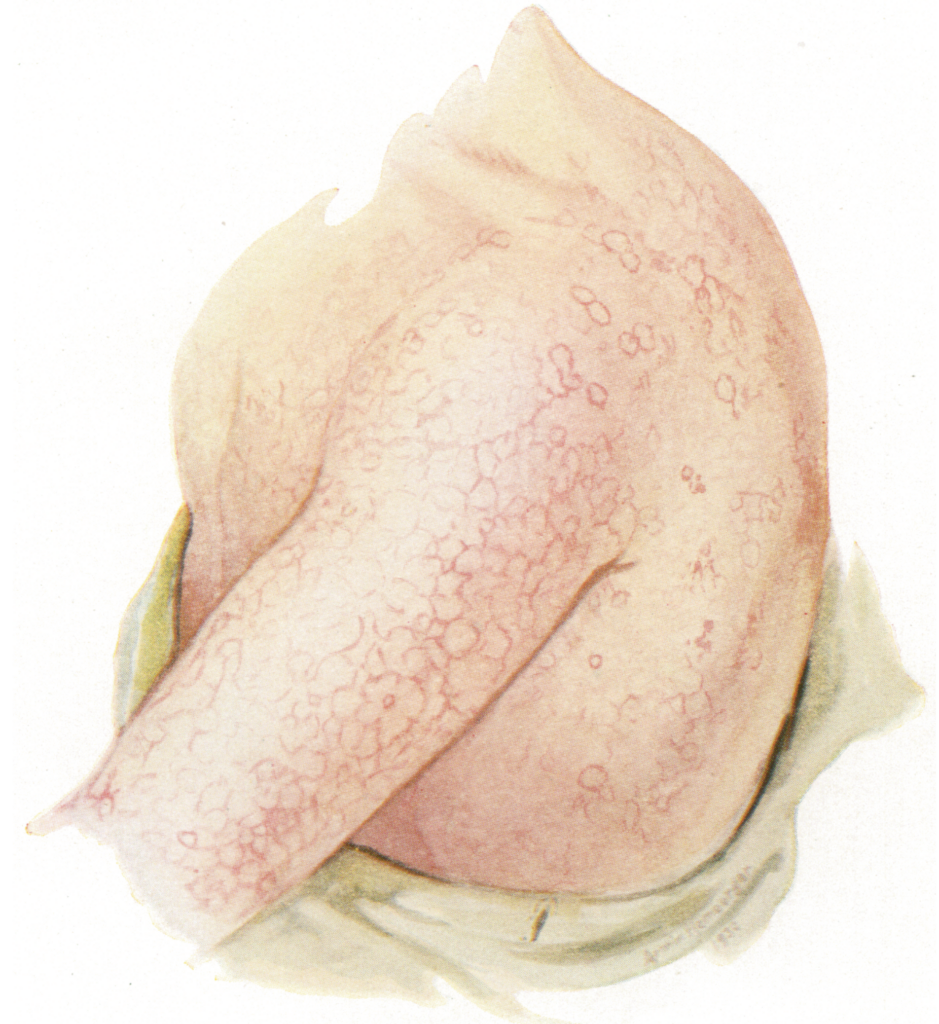

Erythema infectiosum, commonly known as Fifth Disease, is a mild, self-limited exanthematous illness caused by Parvovirus B19. It typically affects school-aged children and is characterised by a biphasic rash—initial facial erythema (“slapped cheek”) followed by a lacy, reticular rash on the body.

Although generally benign, the disease may cause serious complications in certain populations, including transient aplastic crisis in patients with chronic haemolytic anaemias and hydrops fetalis in pregnancy.

Parvovirus B19 is a small, non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA virus of the genus Erythrovirus in the Parvoviridae family. The virus primarily targets erythroid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, and spreads through respiratory droplets. The incubation period is typically 7–10 days, with peak incidence in late winter to early spring.

The condition was historically classified as the “fifth” among the six classic childhood exanthems. It was first clearly associated with Parvovirus B19 following the discovery of the virus by Yvonne Edna Cossart (1934-2014) in 1975 and its linkage to erythema infectiosum in 1983–1984 outbreaks in the UK.

Synonyms of fifth disease: Erythema infectiosum, fifth’s disease, slapped cheek syndrome, erythema contagiosum, örtliche Rötheln, Megalerythema epidemicum, Mégalérythème épidémique, megalerythema epidemicum, exanthema variable, erythema simplex marginatum, erythema infantimi febrile, epidemische kinderrotlauf.

English physician Clement Dukes (1845–1925) introduced the numbering system for childhood exanthems in 1900. He categorised them by clinical presentation into: First: measles; Second: scarlet fever; Third: rubella; and Fourth: Filatov-Dukes disease. Later additions – Fifth: erythema infectiosum (1905, Cheinisse); and Sixth: roseola infantum (1910, Dreyfus)

Clinical Manifestations

Classic presentation:

- Low-grade fever, malaise, headache

- Three-phase rash:

- Facial erythema: Symmetrical, bright red rash sparing perioral area (“slapped cheek”)

- Lacy body rash: Reticulated maculopapular rash starting on limbs, spreading to trunk

- Recurrent rash: May recur for weeks/months triggered by sunlight, exercise, heat, or stress

Other features:

- Rash usually fades without desquamation or pigmentation

- Arthralgia or arthritis (more common in adult women)

- Mild constitutional symptoms (sore throat, cough, low fever)

Diagnosis

- Clinical diagnosis in children is often sufficient during outbreaks

- Confirmatory tests:

- Parvovirus B19 IgM and IgG serology

- PCR for B19 DNA in immunocompromised or prenatal settings

Treatment

- Supportive care only—no antiviral treatment available

- Children not considered contagious once rash appears—no need for exclusion from school

- Immunoglobulin therapy or transfusions may be required in severe chronic or aplastic presentations

- Intrauterine transfusion may be used for foetal hydrops

Differential Diagnosis

- Rubella, measles, scarlet fever

- Roseola infantum

- Drug eruptions

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (especially in teens/adults with arthropathy)

- Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome

Complications

- Transient aplastic crisis (especially in patients with haemolytic anaemias)

- Foetal hydrops, miscarriage, or stillbirth in congenital infections

- Chronic anaemia in immunocompromised patients

- Arthropathy in adults, especially women

- PPGSS (Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome) in adolescents

- Rarely, immune thrombocytopenia, vasculitis, or encephalitis

Parvovirus B19

Parvovirus B19 (B19V) is a small, non-enveloped, single-stranded DNA virus belonging to the family Parvoviridae, subfamily Parvovirinae, genus Erythrovirus. It is the only known parvovirus pathogenic to humans and is a common, community-acquired respiratory pathogen.

B19V targets erythroid progenitor cells in the bone marrow, leading to a range of manifestations depending on the host’s age, immune status, and haematologic background.

Clinical Associations:

- Polyarthropathy: Common in adults, especially women—typically symmetrical, non-erosive, and self-limiting.

- Transient aplastic crisis: Occurs in patients with increased red cell turnover or marrow suppression (e.g. hereditary spherocytosis, sickle cell disease, autoimmune haemolytic anaemia).

- Pregnancy: May cause foetal anaemia, non-immune hydrops fetalis, spontaneous abortion, or intrauterine death if infection occurs in the first half of pregnancy.

- PPGSS (Papular-purpuric gloves and socks syndrome): Painful oedema, erythema, and petechiae of the hands and feet, most often seen in adolescents and young adults.

- Immune-mediated syndromes: Reported triggers include immune thrombocytopenic purpura, Henoch–Schönlein purpura, and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Note: Transient erythroblastopaenia of childhood and true aplastic anaemia are not associated with parvovirus B19 infection.

History of fifth disease

1886 – Anton Tschamer (Graz) described an unusual exanthem in 30 children, distinct from typical rubella. He termed it örtliche Rötheln but considered it an abortive form of German measles due to its atypical facial and limb involvement.

1896 – Adolf Tobeitz (1873-1938) read a paper “Zur Polymorphie und Differential der Rubella” before the 11th International Medical Congress in Moscow. He reported cases which showed “a distinct departure from the general course of rubella“. Theodor Escherich (1857-1911), in the ensuing discussion, proposed that this eruption represented a distinct entity.

1899 – Georg Sticker (1860-1960) coined the term erythema infectiosum in his paper Die neue Kinderseuche in der Umgebung von Giessen. Escherich and his assistant Adolf Schmid studied 121 cases during 1897–1899 epidemics in Graz, publishing the first detailed clinical description

1900 – Clement Dukes numbered the paediatric exanthems to differentiate the variably described and inaccurately labelled rashes of childhood. He divided them based on clinical presentation into: rubeola (first), scarlet fever (second), rubella (third), and Filatov-Dukes (fourth).

1905 – Henry Larned Keith Shaw (1873-1941) illustrated the condition in an American paper based on Viennese cases, renewing transatlantic interest in the disease

1905 – Léon Cheinisse (1871-1924) proposed the name ‘fifth disease‘ (cinquième maladie éruptive) in a paper describing mégalérythème épidémique as clinically and epidemiologically distinct from rubella and scarlet fever.

à côté de ces quatre affections exanthématiques — rougeole, scarlatine, rubéole, pseudo-scarlatine épidémique – , il en est une cinquième qui, décrite d’abord, elle aussi, comme une variété de rubéole, a été ensuite érigée, par différents auteurs et sous des désignations diverses [érythème infectieux aigu, érythème infectieux morbilliforme, megalerythema epidemicum, erythema simplex marginatum, etc.], en entité morbide distincte et indépendante.

Alongside these four exanthematic affections—measles, scarlet fever, rubella, pseudo-epidemic scarlet fever – there is a fifth which, also first described as a variety of rubella, was later supported by different authors and under various designations [erythema infectiosum, erythema infectios morbilliforme, megalerythema epidemicum, erythema simplex marginatum, etc.], as a distinct and independent morbid entity.

1920s–1930s – American outbreaks were described by Zahorsky (1924), Herrick (1926), Feeley (1928) and Lawton and Smith (1931). Photographs accompany those of Herrick and Lawton and Smith.

1957 – Werner et al isolated a cytopathic agent from patients during a 1955 epidemic in Pennsylvania. It was believed to be linked to erythema infectiosum

Werner 1957

- An epidemic of erythema infectiosum was studied during the spring of 1955 in Reading, Pa.

- A cytopathogenic transmissible agent was obtained from monkey kidney cultures inoculated with clinical material.

- The serological data from cases and contacts are suggestive of a relationship between the cytopathogenic agent and the disease erythema infectiosum in humans.

1975 – Australian virologist Yvonne Cossart (1934-2014) identified Parvovirus B19 during hepatitis B screening. The virus was named after serum sample panel “B19” and stored until a clinical association emerged.

1980 – John Pattison et al linked B19 infection to aplastic crisis in sickle cell patients in London. The development of IgM assays confirmed its pathogenic role.

1983 – Mary Anderson et al demonstrated B19-specific IgM in sera of patients during a North London erythema infectiosum outbreak. This confirmed Parvovirus B19 as the causative agent of fifth disease.

Parvovirus-specific IgM was detected in all sera from the 31 cases in children and 2 adolescents. Those sera taken soon after the onset of the rash were strongly positive and the amount of specific IgM diminished as the length of time between the rash and the serum specimen increased. On the basis of these preliminary results we propose that the human parvovirus is the hitherto elusive agent of erythema infectiosum.

Anderson et al 1983

Associated Persons

- Theodor Escherich (1857-1911) – Advocated for erythema infectiosum as a disease sui generis

- Clement Dukes (1845-1925) – Introduced the numerical classification of childhood exanthems

- Georg Sticker (1860-1960) – Coined the term erythema infectiosum; documented epidemiology.

- Henry Larned Keith Shaw (1873-1941) – Published one of the first American illustrated accounts in 1905.

- Léon Cheinisse (1871-1924) – Proposed the name “fifth disease” in 1905.

- Yvonne Cossart (1934-2014) – Identified Parvovirus B19 in 1975.

References

Historical references

- Tschamer A. Ueber örtliche Rötheln. Jahrbuch für Kinderheilkunde und physische Erziehung. 1889; 29: 372-379.

- Tobeitz A. Ueber Rubeola. XII Internationaler medicinischer Congress in Moskau. 1896

- Tobeitz A. Zur Polymorphie und differential Diagnose der Rubeola, Archiv für Kinderheilkunde. 1898; 25: 17.

- Sticker G. Die neue Kinderseuche in der Umgebung von Giessen (Erythema infectiosum). Zeitschrift für praktische Aerzte. 1899; 8(11): 353–358

- Pospischill D. Ein neues, als selbständig erkanntes akutes Exanthem. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift , 1899; 12(7): 181

- Schmid. Aus der Grazer pädiatrischen Klinik (Prof Escherich). Ueber Rötheln und Erythemepidemien. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift , 1899; 12(47): 1169-1173

- Escherich T. Variété d’erythéme infectieux chez les enfants, Congrès international de Médecine Comptes-rendus. 1900, p. 528.

- Shaw HLK. Erythema infectiosum. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 1905; 129: 16-22

- Cheinisse L. Une Cinquième maladie éruptive, le Mégalérythème épidémique. Semaine Médicale, Paris 1905; 25: 205-207

Eponymous term review

- Zahorsky J. An Epidemic of Erythema Infectiosum, American journal of diseases of children, 1924; 28(2): 261-262

- Herrick TP. Erythema Infectiosum, American journal of diseases of children. 1926; 31(4): 486-495

- Feeley JB. Erythema Infectiosum, Atlantic Medical Journal. 1928; 31: 752

- Lawton AL, Smith RE. Erythema infectiosum: A clinical study of an epidemic in Branford. Conn. Arch Intern Med (Chic). 1931; 47(1): 28-41.

- Werner GH, Brachman PS, Ketler A, Scully J, Rake G. A new viral agent associated with erythema infectiosum. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1957 apr 19;67(8):338-45.

- Cossart YE, Field AM, Cant B, Widdows D. Parvovirus-like particles in human sera. Lancet. 1975 Jan 11;1(7898):72-3.

- Pattison JR, Jones SE, Hodgson J, Davis LR, White JM, Stroud CE, Murtaza L. Parvovirus infections and hypoplastic crisis in sickle-cell anaemia. Lancet. 1981 Mar 21;1(8221):664-5.

- Anderson MJ, Jones SE, Fisher-Hoch SP, Lewis E, Hall SM, Bartlett CL, Cohen BJ, Mortimer PP, Pereira MS. Human parvovirus, the cause of erythema infectiosum (fifth disease)? Lancet. 1983 Jun 18;1(8338):1378.

- Anderson MJ, Lewis E, Kidd IM, Hall SM, Cohen BJ. An outbreak of erythema infectiosum associated with human parvovirus infection. J Hyg (Lond). 1984 Aug;93(1):85-93.

- Anderson LJ. Role of parvovirus B19 in human disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987 Aug;6(8):711-8.

- Musiani M, Manaresi E, Gallinella G, Cricca M, Zerbini M. Recurrent erythema in patients with long-term parvovirus B19 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Jun 15;40(12):e117-9

- Rogo LD, Mokhtari-Azad T, Kabir MH, Rezaei F. Human parvovirus B19: a review. Acta Virol. 2014;58(3):199-213.

- Qiu J, Söderlund-Venermo M, Young NS. Human Parvoviruses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017 Jan;30(1):43-113.

eponymictionary

the names behind the name

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |

[…] In 1905, Léon Cheinisse added erythema infectiosum (fifth), and in 1910 John Zahorsky added roseola […]