Inhalational Emergency

aka Pediatric Perplexity 005

A toddler was brought to the emergency department for increasing respiratory distress over the past few days. He has also had fevers, and was started on antibiotics by his family doctor with no improvement.

In the emergency department he had SaO2 of 89% OA and was treated with oxygen. Prominent wheeze, with decreased air entry and occasional crackles were noted, predominantly on the right-side of his chest. He showed no response to repeatedly nebulised bronchodilators.

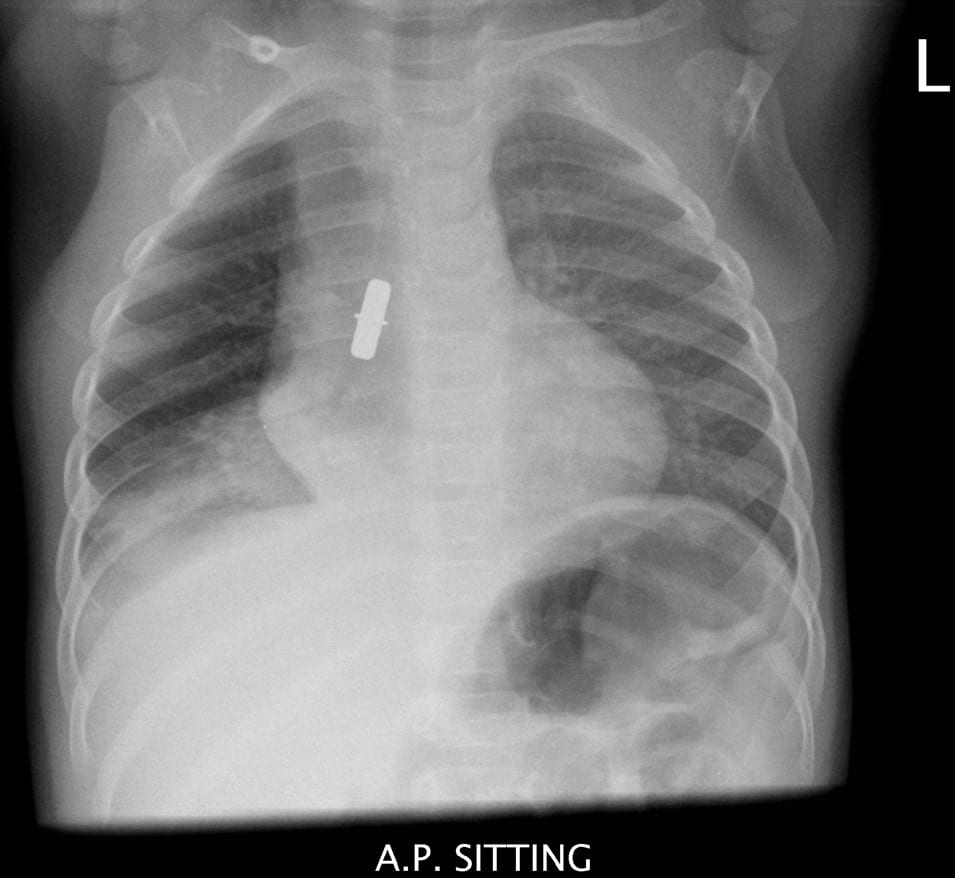

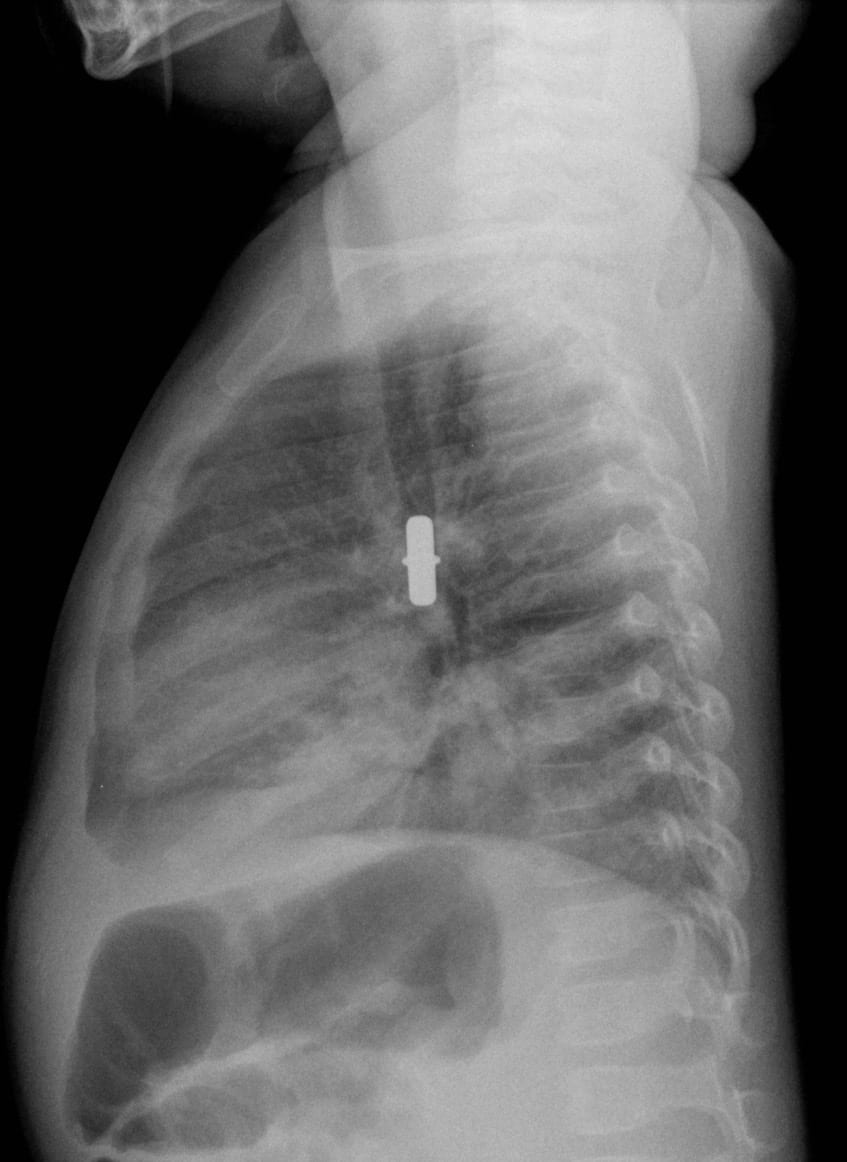

Given this lack of response to therapy, chest radiographs were ordered:

Questions

Q1. What do the chest radiographs show?

Answer and interpretation

A foreign body in the right main bronchus. There is atelectasis (collapse) predominantly affecting the right lower lobe (note the distinct right heart border on the AP film, and patchy opacities below the foreign body on the lateral film).

Further history revealed that the child’s parents had recently assembled some new Swedish furniture at home… Perhaps its a bit wobbly?

Q2. What objects are usually aspirated by children and which are most dangerous?

Answer and interpretation

Round-shaped foods are the most frequently aspirated objects:

Peanuts, grapes, raisins, and hot dogs…

Nonfood objects include all sorts of items — such as metal dowels from Swedish furniture. Conformable objects are the most difficult to manage and remove. Balloons are the objects most likely to result in death.

Q3. What is the pathophysiological significance of the size of the aspirated object?

Answer and interpretation

Large objects tend to lodge in the upper airway and trachea (about 20% of airway foreign bodies). They are likely to cause obvious and dramatic signs of upper airway obstruction such as dyspnea, drooling, stridor, and cyanosis — which may ultimately cause death unless expeditiously removed.

More common are smaller objects that pass through the subglottic space. They will usually lodge in a bronchus — usually the right main bronchus — or in a more terminal part of the airway.

Q4. What are the clinical features of lower airway foreign body aspiration?

Answer and interpretation

From the history:

- Coughing or choking episodes while eating solid foods (classically nuts), or while sucking a small plastic toy or similar object. This history should never be dismissed — a foreign body is almost always present in the symptomatic child.

- Persistent coughing and wheezing.

- Delayed presentations may shows symptoms of infection due to secondary tracheitis, bronchitis, atelectasis or pneumonia.

If foreign body ingestion was unwitnessed, there may be no history of aspiration (about 15% of cases).

On examination there may be:

- no physical signs

- reduced breath sounds over all or part of one lung

- Wheeze

- Features of a secondary tracheitis, bronchitis, atelectasis or pneumonia if presentation is delayed

Q5. Why is a high index of suspicion for foreign body aspiration essential?

Answer and interpretation

A high index of suspicion is needed as aspirated foreign body is frequently missed.

Parents may not volunteer the history of possible inhalation if aspiration was not witnessed (I’m repeating myself on purpose…). Delayed diagnoses up to 5 years have been reported!

In particular, beware of the sudden onset of a first wheezing episode in a toddler in whom there is no history of allergy, especially if it follows a choking episode.

Q6. What investigations are useful in assessing possible lower airway foreign body aspiration?

Answer and interpretation

Chest radiographs may show:

- radio-opaque foreign bodies

- obstructive hyperinflation (asymmetric)

- collapse/ atelectasis

- normal (15% of lower airway foreign body aspirations)

Some clinicians prefer full inspiration and full expiration films to check for hyperinflation (impossible in the uncooperative toddler). An alternative is to perform lateral decubitus films, looking for the absence of of decreased lung volume when the obstructed side is dependent. The films should include the nasopharynx to the chest.

A normal chest radiograph does not exclude the presence of a foreign body

Bronchoscopy is indicated for all patients with a suspected inhaled foreign body, even if the chest radiograph is ‘normal’ — unless the child is completely asymptomatic with a normal physical and radiographic examination.

Q7. Describe the management of a lower airway foreign body.

Answer and interpretation

Supportive care and monitoring (including oxygen therapy if required) pending bronchoscopy.

Bronchoscopy is best performed by an expert paediatric endoscopist teamed with an experienced paediatric anaesthetist in a major children’s hospital. Rigid bronchoscopy is generally the procedure of choice for removal of the object.

Removal of the foreign body usually improves symptoms. Corticosteroids or antibiotics are not usually indicated.

Q8. How can paediatric foreign body aspiration be prevented?

Answer and interpretation

Short of sewing shut the mouths of toddlers, there is no definitive prevention strategy…

Feed children age-appropriate food:

- No child <15mo should be offered foods such as popcorn, hard lollies, raw carrot or apples.

- Children < 4 y should not be offered peanuts.

- Encourage the child to sit quietly while eating (as if that’s going to work…) and offer food one piece at a time.

Avoid toys with small parts for children <3 years.

Don’t leave small objects lying around — especially after assembling your new furniture.

References

- Cohen S, Avital A, Godfrey S, Gross M, Kerem E, Springer C. Suspected foreign body inhalation in children: What are the indications for bronchoscopy?. J Pediatr 155. 276-280.2009 PMID: 19446848

- D’Agostino J. Pediatric airway nightmares. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010 Feb;28(1):119-26. PubMed PMID: 19945602.

CLINICAL CASES

Paediatric Perplexity

Chris is an Intensivist and ECMO specialist at the Alfred ICU in Melbourne. He is also a Clinical Adjunct Associate Professor at Monash University. He is a co-founder of the Australia and New Zealand Clinician Educator Network (ANZCEN) and is the Lead for the ANZCEN Clinician Educator Incubator programme. He is on the Board of Directors for the Intensive Care Foundation and is a First Part Examiner for the College of Intensive Care Medicine. He is an internationally recognised Clinician Educator with a passion for helping clinicians learn and for improving the clinical performance of individuals and collectives.

After finishing his medical degree at the University of Auckland, he continued post-graduate training in New Zealand as well as Australia’s Northern Territory, Perth and Melbourne. He has completed fellowship training in both intensive care medicine and emergency medicine, as well as post-graduate training in biochemistry, clinical toxicology, clinical epidemiology, and health professional education.

He is actively involved in in using translational simulation to improve patient care and the design of processes and systems at Alfred Health. He coordinates the Alfred ICU’s education and simulation programmes and runs the unit’s education website, INTENSIVE. He created the ‘Critically Ill Airway’ course and teaches on numerous courses around the world. He is one of the founders of the FOAM movement (Free Open-Access Medical education) and is co-creator of litfl.com, the RAGE podcast, the Resuscitology course, and the SMACC conference.

His one great achievement is being the father of three amazing children.

On Twitter, he is @precordialthump.

| INTENSIVE | RAGE | Resuscitology | SMACC