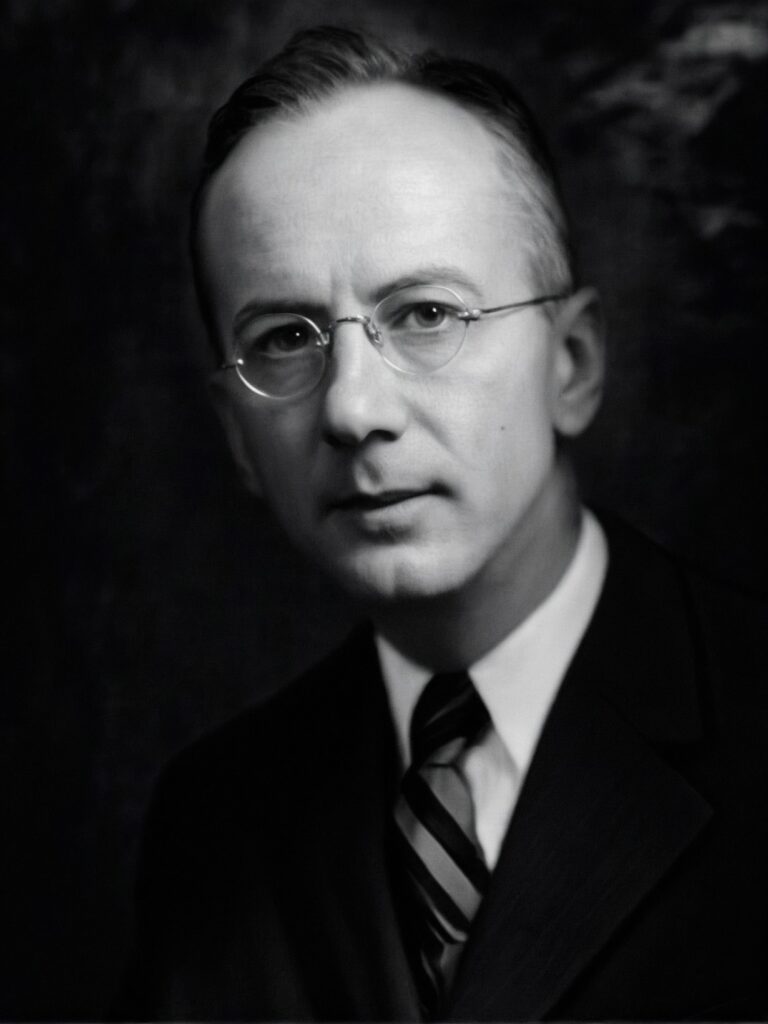

Louis Hamman

Louis Virgil Hamman (1877-1946) was an American physician.

Hamman was a renowned American physician and diagnostician, best remembered for his sharp clinical acumen, compelling teaching style, and contributions to the understanding of pulmonary disease and diabetes. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, Hamman initially considered a religious vocation before turning to medicine. He earned his M.D. from Johns Hopkins in 1901, later joining the faculty and spending his career at the institution.

He held numerous prestigious roles, including Associate Professor of Medicine and acting chair of the department during WWI. His clinical brilliance was most evident during the revered weekly clinico-pathological conferences at Johns Hopkins. Described by peers as kind, humble, and deeply philosophical, Hamman’s humanity permeated both his bedside manner and scholarly work.

Hamman made several important medical contributions, especially in the realm of spontaneous mediastinal emphysema and diffuse interstitial lung disease. He is eponymously associated with Hamman’s sign, Hamman’s syndrome, and the Hamman-Rich syndrome, the latter co-described with Arnold Rice Rich (1893–1968). His later writings reflect a deep introspection on medicine’s humanistic elements, and his 1938 essay “As Others See Us” remains a classic.

Biography

- Born December 21, 1877 in Baltimore, Maryland

- 1895 – Received A.B. from Rock Hill College, Ellicott City, Maryland

- 1901 – Earned M.D. from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

- 1901–1903 – Internship and residency at New York Hospital

- 1903 – Returned to Johns Hopkins; became head of the Phipps Tuberculosis Clinic

- 1912 – Co-authored Tuberculin in Diagnosis and Treatment with Samuel Wolman

- 1914 – Published on spontaneous pneumothorax

- 1918–1919 – Acting Chair of Medicine, Johns Hopkins (WWI)

- 1924 – Published on prognosis of angina pectoris

- 1935 – Described diffuse interstitial pulmonary fibrosis with Arnold Rich (Hamman-Rich syndrome)

- 1937–1939 – Presented on spontaneous interstitial and mediastinal emphysema (Hamman’s sign and Hamman syndrome)

- 1941 – Elected President of the Association of American Physicians

- 1944 – Co-authored seminal paper on acute diffuse interstitial fibrosis of the lungs

- 1945 – Delivered Frank Billings lecture, Mediastinal Emphysema

- Died April 28, 1946 at Johns Hopkins Hospital, aged 68

- 1950 – Louis Hamman Memorial Scholarship established at Johns Hopkins

- 1975 – Johns Hopkins General Medical Clinic renamed the Hamman-Baker Medical Clinic

Medical Eponyms

Hamman’s sign / Hamman’s cruch (1934)

Crunching, bubbling, or rasping sound synchronous with the heartbeat, heard on auscultation in spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. The sound is caused by the heart beating against air-filled tissues and is typically heard best over the left lateral position.

Hamman’s sign is associated with conditions such as pneumomediastinum or pneumopericardium, and can be seen in cases of tracheobronchial injury, medical procedures, rupture of a proximal pulmonary bleb and Boerhaave syndrome. The Incidence of Hamman sign is estimated around 12.2% in pneumomediastinum.

1934 – Hamman published an article outlining five conditions which mimic the pain and symptoms of coronary artery occlusion ‘upper abdominal disease, pericarditis, pulmonary embolism, rupture of the aorta and interstitial emphysema of the lungs‘

Now, when almost every sudden, severe pain in the chest of a person past middle life is at once called coronary occlusion, seems the appropriate time to sound a warning. There are other diseases of the heart, lungs and abdominal organs which may so closely resemble coronary occlusion that they are often distinguishable from it only with great difficulty and sometimes not until autopsy

He outlined three cases of ‘interstitial emphysema of the lungs‘ with description of the sound heard on auscultation

…if the air escapes into the interstitial fibrous bands of the lung and travels only to the mediastinum then the similarity may be very confusing. With the escape of air and the tearing apart of the fibrous tissue there is sudden severe pain…The systolic crunching sound which is heard over the heart may easily be mistaken for a pericardial friction If the observer is not familiar with the peculiar symptoms which accompany this accident, coronary occlusion may be erroneously diagnosed

1937 – Hamman described six cases of spontaneous interstitial emphysema of the lungs. He used the term ‘spontaneous mediastinal emphysema‘ and concluded that it was typically a benign and self-limiting condition, often misdiagnosed as coronary artery occlusion or pericarditis.

He also noted that interstitial emphysema could be easily reproduced experimentally by artificially increasing intrapulmonary pressure—e.g., inflating the lungs with a pump. In such cases, air tracked to the mediastinum via bronchovascular pathways, often appearing shortly thereafter in the subcutaneous neck tissues and sometimes producing pneumothorax concurrently.

1939 – Hamman defined the ‘crunching sound‘ heard in relation to mediastinal emphysema in a series of cases presented in the the second Henry Sewall Lecture at Johns Hopkins Medical School in 1939.

Case 1: Dr. Esler heard the sound and interpreted it to be a pericardial friction. This seemed to confirm the diagnosis of coronary occlusion…I examined the heart and the lungs with the greatest care and could detect nothing that was to the least degree abnormal. When I expressed chagrin at my lack of skill, the patient laughingly said that he could easily bring on the sound which had excited so much interest.

He turned on his left side and after shifting about for a few moments said, “There it is, I hear it now.” I put my stethoscope over the apex of the heart and with each impulse there occurred the most extraordinary crunching, bubbling sound. It is difficult to describe. Crunching is the best adjective I can think of though it is far from apt, especially since crunching has been widely used to describe pleural friction, to which it bore no resemblance. It certainly conveyed the impression of air being churned or squeezed about in the tissues.

Hamman further defined the auscultation findings in spontaneous mediastinal emphysema in 1945.

I have no doubt that at times the distinctive auscultatory signs may be absent, although in their absence it would be difficult to decide with certainty that mediastinal emphysema is present.

These peculiar sounds consist of crackles, bubbles or churning sounds heard with each contraction of the heart. They may be heard only during systole or during systole and diastole, but always with systolic accentuation. They may be so soft that to be heard they must be listened for attentively; they may be so loud that they can be heard at a distance. Very often the patient himself is aware of the sounds and calls attention to them. They may be loudest over the lower portion of the sternum and to the left of the sternum or near the apex of the heart. They may be heard when the patient sits up and disappear when he lies down or be plainly heard when he lies on the left side and absent in other positions.

Hamman, 1945

Hamman-Rich syndrome (1935)

This eponymous name previously referred to as ‘acute diffuse idiopathic interstitial pulmonary fibrosis of unknown aetiology‘ and now known as Acute Interstitial Pneumonia (AIP).

Hamman and American pathologist Arnold Rice Rich (1893-1968) described the rapid proliferation of connective tissue and fibrosis following a chest infection. Often misrepresented as Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS).

From the Pathological Anatomy and the symptoms of these four patients we may reconstruct the course of an uncommon and remarkable disease. Pulmonary inflammation develops insidiously with little local or constitutional disturbance. Very shortly after the onset of pulmonary infection there occurs a marked proliferation of connective tissue which greatly thickens the alveolar walls and obliterates many of the air sacs and soon dyspnea comes on and grows increasingly severe as a result of the fibrosis which disturbs the relation of the alveolar capillaries to the air spaces and encroaches upon the alveoli themselves. At an early stage of the disease the exudate may be so extensive throughout all lobes of both lungs that acute suffocation occurs. At a later stage, as happened in two of our cases, the patient may die of a slowly progressing suffocation.

By Stigler’s law of eponomy, Hamman and Rich were not the first to describe this process. The first documented pathological review of the disease process was by Sir Dominic John Corrigan (1802-1880) in a process he termed ‘cirrhosis of the lung‘. Later in 1897 by Rindfleisch as Cirrhosis Cystica Pulmonum

Hamman syndrome (1939)

Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema without an apparent precipitating cause. Often presents in young adults with chest pain and dyspnoea. Related physiologically to but distinct from the Macklin effect

Often incorrectly referred to as Macklin effect (1937) which comparatively described the pathophysiology whereby increased alveolar pressure caused alveolar rupture. However this is a involved in primary and secondary pneumomediastinum.

Hamman syndrome is estimated to have an incidence of 1 in 30,000.

Major Publications

- Hamman L, Wolman S. Tuberculin in diagnosis and treatment. 1912

- Hamman L. Spontaneous Pneumothorax. Trans Am Climatol Clin Assoc. 1914;30:273-89.

- Hamman L. The Prognosis of Angina Pectoris. Trans Am Climatol Clin Assoc. 1924;40:48-59

- Hamman L. Remarks on the diagnosis of coronary occlusion. Annals of Internal Medicine 1934; 8(4): 417-431

- Hamman L, Rich AR. Fulminating Diffuse Interstitial Fibrosis of the Lungs. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1935; 51: 154-163. [Hamman-Rich syndrome]

- Hamman L. Spontaneous interstitial emphysema of lungs. Transactions of the Association of American Physicians 1937; 52: 311–319 [** Most commonly quoted paper cited for the Hamman sign is Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1937; 52: 311–319 however, this paper does not exist]

- Hamman L. As others see us. Transactions of the Association of American Physicians. 1938; 53: 22.

- Hamman L. Spontaneous mediastinal emphysema. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital 1939; 64: 1-21 [Hamman syndrome]

- Hamman L, Rich AR. Acute diffuse interstitial fibrosis of the lungs. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital 1944; 74(3): 177–212. [Hamman-Rich syndrome]

- Hamman L. Mediastinal emphysema: The Frank Billings lecture. JAMA, 1945; 128: 1-6.

References

Biography

- Ulmann, D. Louis Virgil Hamman. In: A book of portraits of the faculty of the Medical Department of the Johns Hopkins University. 1922 [full image]

- Louis Hamman. The Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine 1893-1905. 1943

- Fort W. Dr. Louis Hamman. Annals Of Internal Medicine. 1946; 25: 187

- Louis Hamman. JAMA. 1946; 131(4): 350

- Wainwright CW. Dr. Hamman as I knew him. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1954;66:1-9.

- Harvey JC. The writings of Louis Hamman. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1954; 95(4): 178-189

- Wainwright CW. Dr. Hamman as I knew him. Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1955; 96(1): 29-34

- Portait: Louis Virgil Hamman. Johns Hopkins Medical Collection

Eponymous terms

Hamman-Rich

- Corrigan DJ. On cirrhosis of the lung. The Dublin Journal of Medical Science, 1838; 13: 266-286.

- Rindfleisch GE. Ueber Cirrhosis Cystica Pulmonum. Zentralblatt für allgemeine Pathologie und pathologische Anatomie 1897; 8: 864–865.

- Bouros D, Nicholson AC, Polychronopoulos V, du Bois RM. Acute interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(2):412-418

Hamman Syndrome

- Macklin CC. Pneumothorax with Massive Collapse from Experimental Local Over-inflation of the Lung Substance. Can Med Assoc J. 1937 Apr; 36(4): 414–420.

- Newcomb A, Clarke P. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a benign curiosity or a significant problem? Chest. 2005 Nov;128(5):3298-302.

Hamman sign

- Editorial. Hamman’s Sign of Mediastinal Crunch in Mediastinal Emphysema. Virginia Medical Monthly 1966; 63: 106-108

- Baumann MH, Sahn SA. Hamman’s sign revisited. Pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum? Chest. 1992 Oct;102(4):1281-2.

- Macia I, Moya J, Ramos R, Morera R, Escobar I, Saumench J, Perna V, Rivas F. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: 41 cases. Eur Cardio-Thoracic Surgery J. 2007 June 31;6:1110–1114

- Alexandre AR, Marto NF, Raimundo P. Hamman’s crunch: a forgotten clue to the diagnosis of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. BMJ Case Rep. 2018

- Thakeria P, Danda N, Gupta A, Anand D. Smartphone aiding in analysis of Hamman’s sign. BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Nov 19;12(11):e231418.

- Jimidar N, Lauwers P, Govaerts E, Claeys M. The clicking chest: what exactly did Hamman hear? A case report of a left-sided pneumothorax. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020 Nov 12;4(6):1-5

Eponym

the person behind the name

BA MA (Oxon) MBChB (Edin) FACEM FFSEM. Emergency physician, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital. Passion for rugby; medical history; medical education; and asynchronous learning #FOAMed evangelist. Co-founder and CTO of Life in the Fast lane | On Call: Principles and Protocol 4e| Eponyms | Books |