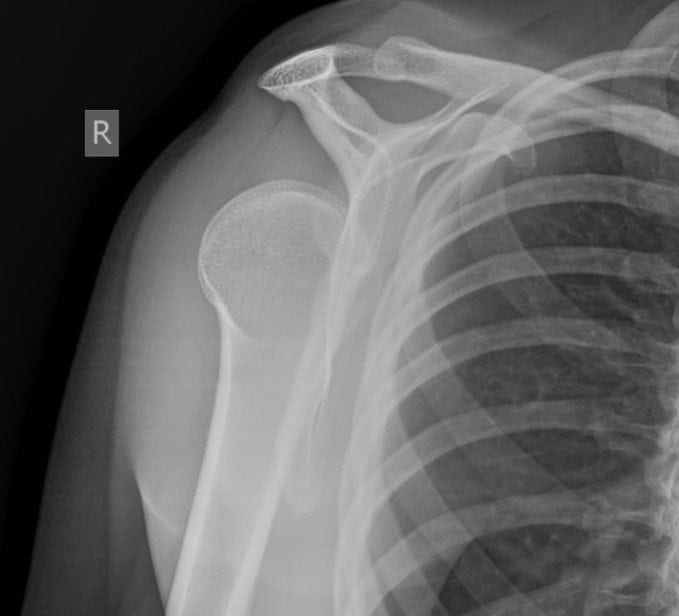

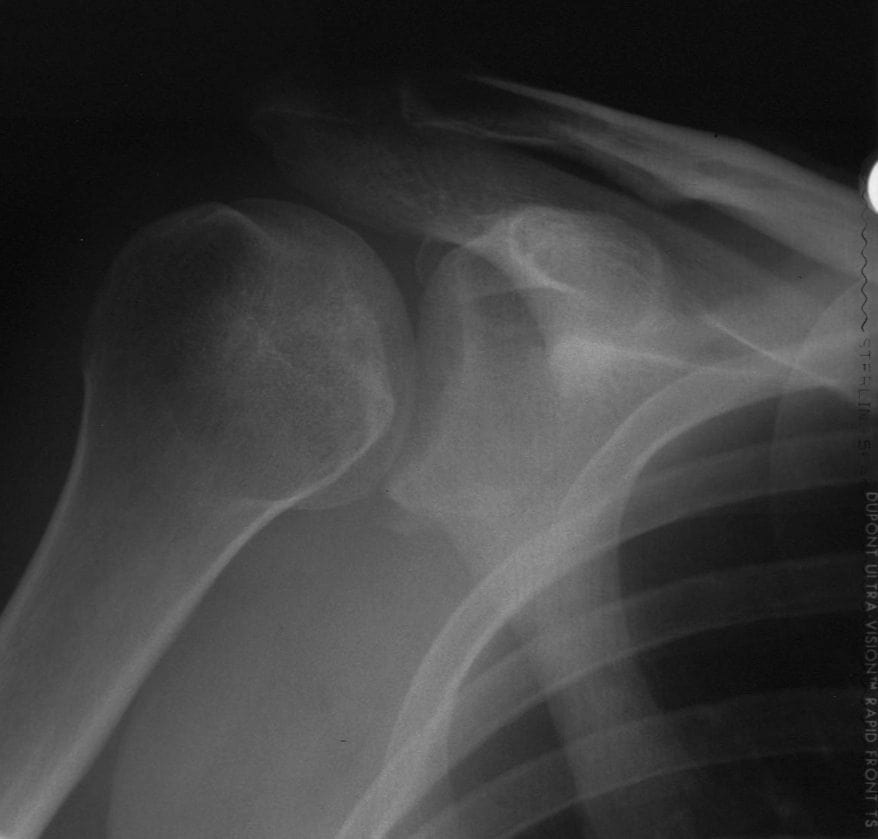

Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

Posterior Shoulder Dislocation Discussion

What does these X-rays show? What signs do you look for on x ray for this condition? What other images would you order to confirm/rule out your diagnosis?

Posterior Shoulder Dislocation

Posterior shoulder dislocations make up a small minority of total shoulder dislocation cases, accounting for 2-4% of presentations. However because of a low level of clinical suspicion and insufficient imaging, they are often missed.

Approximately half of posterior shoulder dislocations go undiagnosed on initial presentation.

Mechanism

Traditionally posterior dislocations have been associated with epileptic seizures, high energy trauma, electrocution and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), although the incidence associated with ECT especially has decreased somewhat in recent years.

Often a posterior dislocation is accompanied by a fracture of the neck of humerus or fractures of the tuberosities. However discussion here will be limited to simple dislocations.

In traumatic posterior dislocations, the injury is almost always due to a fall onto an outstretched, internally rotated arm. The force of the impact pushes the head of the humerus posteriorly out of the glenoid cavity.

An impaction fracture of the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head (McLaughin lesion or reverse Hill-Sachs lesion) may result from the humerus being forced against the posterior lip of the glenoid.

If enlocation is delayed, it can worsen the severity of this lesion and lead to further complications. Dislocation may also result in capsulolabral tears, glenoid rim fractures or rotator cuff tears.

When a bilateral posterior dislocation is present, it is almost always secondary to seizure activity. With seizure activity, the internal rotator muscles (teres major and subscapularis) overpower the external rotator muscles (teres minor, infraspinatus) to dislocate the head of humerus.

A posterior dislocation should be considered as a differential in any episode of shoulder pain and immobility after a seizure.

Rotator cuff muscles: capsule of muscles and tendons that collectively stabilize the glenohumeral joint.

- Teres minor: intrinsic shoulder muscle responsible for lateral / external rotation of the arm at the shoulder

- Supraspinatus: joint stabilizer, involved with abduction of the humerus, and contribute weakly to lateral rotation of the humerus

- Infraspinatus: inserts on the middle facet of the greater tuberosity. Its primary function is the external rotation of the shoulder joint and the abduction of the scapula.

- Subscapularis: internally rotates the humerus and in certain positions, the subscapularis provides adduction and extension

- Teres major: originates from a lower one-third of the lateral scapula. It inserts medially to the intertubercular groove. Its function is to provide shoulder extension, adduction, and internal rotation

Incidence

The shoulder joint is the most commonly dislocated joint presenting to hospital. Posterior dislocations account for 2-4% of all shoulder dislocations. Approximately 15% of these cases are bilateral posterior shoulder

The highest incidence of posterior dislocation is in males between the ages of 35 and 55, this is thought to be due to a higher incidence of high impact trauma secondary to a higher level of sporting and motor vehicle related injuries in this group. A larger muscle mass around posterior shoulder girdle in men may also contribute to dislocation during seizure activity.

Presentation

Most cases will present with a history of traumatic injury, a fall onto an outstretched arm or seizure activity. Non epileptic seizures such as drug withdrawal or hypoglycaemia should also be considered. Although an acute dislocation would be associated with considerable pain, pain may be reduced in acute cases due to reduced nociception post seizure, or the ongoing effects of drugs.

Chronic cases are more likely to present with decreased mobility rather than pain as the primary concern. The patient may present complaining of loss of movement, and difficulty with activities like combing their hair or washing their face. A diagnosis of posttraumatic stiff shoulder or frozen shoulder may have been made.

Typically the arm is held in internal rotation and adduction. The most significant finding on examination is a limited range of active and passive external rotation of the effected arm as the head of the humerus is caught to the glenoid rim. Palpation of the humeral head in a posterior position is the only other clear diagnostic feature on examination. Other physical signs such as increased prominence of the coracoid process and acromion anteriorly, and the head of humerus posteriorly may be present but are less significant.

Example: Delayed presentation

Below is an example of ‘missed‘ bilateral posterior shoulder dislocations in a patient post motor vehicle accident with significant head injury and a long term ICU patient with tracheostomy

Complications

- Osteonecrosis of the humeral head

- Acute re-dislocation

- Recurrent posterior shoulder instability

- Joint stiffness and functional incapacity

- Post-traumatic osteoarthritis

Radiological findings

The ideal image for identifying a posterior dislocation is a axillary film, with the patients arm abducted at 70-90 degrees and the image taken from an angle of 45 degrees through the axilla.

This should be done as part of a standard set of imaging after shoulder injury, along with an AP and lateral view of the shoulder. An AP film alone is not adequate to rule out a posterior dislocation, as the film is often normal or near normal.

Several radiological signs have been described on AP view, these include:

- Lightbulb sign – The head of the humerus in the same axis as the shaft producing a lightbulb shape

- Internal rotation of the humerus

- The ‘rim sign’ – Widening of the glenohumeral space

- The ‘vacant glenoid sign‘ – Where the anterior glenoid fossa looks empty

- The ‘trough sign‘ – a vertical line made by the impression fracture of the anterior humeral head

If pain or muscle spasm limits movement and an axillary film cannot be taken, alternative imaging techniques can be used:

- Axillary view, rolled cassette – if the patient is unable to abduct their arm, a rolled cassette can be placed in the axilla, a similar image is obtained, with some magnification and distortion at the edges

- Transthoracic lateral view – lateral film with the normal arm raised over the patients head, and the beam travelling horizontally through the normal axilla

- Trans-scapular view – taken posterior to anterior, with the beam directed along the line of the long axis of the scapula

- Valpeau view – standing with their back against a table, with their upper body bent back at 40-65 degrees, the beam is directed vertically through the shoulder from above

Further Imaging

CT imaging may be used, and can better definition of osseus lesions, occult humeral head and neck fractures, its use is usually as a guide to treatment rather than as a diagnostic tool. 3D CT reconstructions can also be used for planning operative reconstructive surgery.

MRI scanning can be used to more precisely visualise soft tissue and rotator cuff injury. Ultrasound imaging has been used in the diagnosis of posterior dislocation, however its limitations in identifying damage to bony structures limits its use beyond screening tool.

3D CT reconstruction

Management

Treatment course depends on the degree of injury and when it occured. For simple dislocation where the impression fracture affects less that 25% of the humeral head, diagnosed immediately or within 6 weeks of injury, closed reduction should be attempted under general anaesthetic.

Reduction can be attempted using the Depalma method, where the effected arm is first adducted and internally rotated, with caudal traction applied. Then, maintaining traction and internal rotation, the medial aspect of the upper arm is pushed laterally, disengaging the humeral head from the glenoid fossa. Finally the arm is extended, and the humerus falls back into place.

Stability of the joint should be assessed after reduction, and the joint immobilised in a neutral or externally rotated position for 4 weeks. If joint instability is present after reduction, it can be treated either by immobilisation, or by an adjunctive stabilisation procedure.

If closed reduction is not successful, open reduction may be performed. Usually this is in the case of delayed diagnosis or a larger degree of damage to the head of humerus.

References

- Wu J, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Scapulohumeral Muscle. StatPearls

[cite]

Are you aware of any case report of using the Cunningham Method, or similar technique where conscious sedation is not utilized, to reduce a posterior shoulder dislocation ? I had such a case in my urgent care clinic and was able to successfully reduce a posterior shoulder dislocation with the Cunningham method. All confirmed by Xray, of course.

Hi Barry. Posterior dislocations are a strange beast. In the old days most were reduced by abducting the arm for the axial shoulder view. Personally, never used sedation for posterior shoulder reduction just slow distal traction and abduction normally all that is required.

This morning, I had a traumatic posterior dislocation, that reduced very easily using the Davos method. I had the patient shrug his shoulders while leaning backwards.